ART

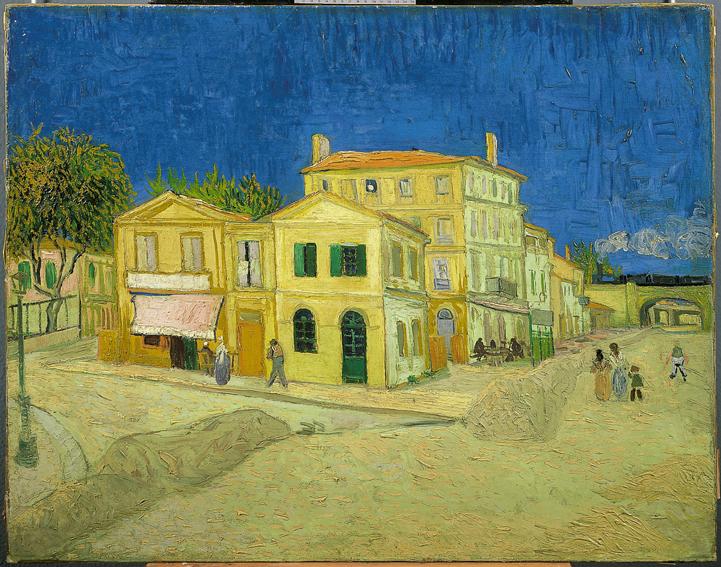

In 1888, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin spent nine weeks living together in Arles. It was a time of astonishing creativity, culminating in a catastrophic falling-out. For his new book, Martin Gayford uncovered the true story of life in the Yellow House. On the evening of December 22 1888, Gauguin sat down to write a long, long letter to his friend, the French artist Claude Emile Schuffenecker - the longest communication he had sent to anybody since he arrived in Arles. Its copiousness suggested that he no longer had anyone to talk to closer to hand. Communications had broken down completely in the Yellow House.

Schuffenecker had replied, offering Gauguin hospitality in Paris, but Gauguin still wasn't quite ready to leave Arles. Gauguin thanked him for his offer; he wasn't coming straight away, but he might on an instant:

"I'm staying here for now, but I'm poised to leave at any moment. My situation here is painful; I owe much to [Theo] Van Gogh and Vincent and despite some discord I can't bear a grudge against a good heart who is ill and suffers and wants to see me."

Two considerations still restrained Gauguin from going. One was that he felt guilty about deserting Vincent. The other was that he was concerned about how Vincent's brother Theo might react if he did. "I need Van Gogh," he confided in Schuffenecker. The letter went on and on, quite unlike the brief notes Gauguin had sent Schuffenecker earlier in his stay. He was concerned that his sales through Theo had dried up. This was because the financial outlook was grim. His allegorical painting Human Miseries, which had not been sold, meant a lot to him; he would like Schuffenecker, who had a private income, to buy it (as he eventually did). He described the frame it should have: black with a yellow line on the inside edge.

"If I am able to leave," he announced, "in May with life assured in Martinique for 18 months I will almost be a happy mortal." He hoped to be followed there by his disciples, "all those who have loved and understood me". Gauguin elaborated his ideas of a better world in which men would live happily together under the tropical sun. But simultaneously he foresaw that his path in life would be lonely. In doing so he revealed how completely he had now absorbed Vincent's mental landscape. "Vincent," he noted, "sometimes calls me 'the man who has come from far away and will go far'."

Gauguin wrote on, for nine pages. Eventually, he closed his letter, even though, that "rainy evening", he could have gone on until morning. Under his signature, he did a little drawing of a memorial plaque he had invented for himself. It was a cartouche, bearing the date and the initials PGo, spelling out "pego", or "the prick".

Gauguin wrote Schuffenecker's address with a flourish, and then walked out into the rain to post the letter. He had missed the last collection of Saturday 22nd, which went at 10 o'clock, but his letter was in time for one of the first express trains on the following day, Sunday 23rd. That was the day on which the catastrophe, so long impending, finally occurred. Vincent continued to paint La Berceuse, his experimental canvas of a mother rocking a cradle. In an attempt to lure Gauguin into staying at the Yellow House, he reminded him that the great Degas had said he was "saving himself up for the Arlésiennes". If the women of Arles were good enough for Degas, surely the place had enough interest for Gauguin?

At some point he asked Gauguin point-blank if he was about to go. Gauguin described the encounter to Emile Bernard a few days later:

"I had to leave Arles, he was so bizarre I couldn't take it. He even said to me, 'Are you going to leave?' And when I said 'Yes' he tore this sentence from a newspaper and put it in my hand: 'The murderer took flight'."

These words were printed at the end of a small news item in the day's edition of L'Intransigeant. An unfortunate young man, one Albert Kalis, had been stabbed from behind while walking home at night. He had been taken to Bicêtre hospital in a desperate condition. "The murderer took flight."

The painters - according to Gauguin's much later recollection - proceeded to have their supper, cooked by Gauguin, as usual. Gauguin "bolted" his and went out to walk in Place Lamartine. He gave two quite different accounts of what happened next, and he was the only witness, because Vincent's memory of that night was very vague. He told the following story to Bernard, who narrated it to the critic Albert Aurier:

"Vincent ran after me - he was going out; it was night - I turned round because for some time he had been acting strangely. But I mistrusted him. Then he told me, 'You are silent, but I will also be silent.' "

Fifteen years later, Gauguin gave a more sensational version of the encounter:

"I felt I must go out alone and take the air along some paths that were bordered by flowering laurels. I had almost crossed the Place Victor Hugo when I heard behind me a well-known step, short, quick, irregular. I turned about on the instant as Vincent rushed towards me, an open razor in hand. My look at that moment must have had great power in it, for he stopped and, lowering his head, set off running towards the house."

This was vivid, but there were several indications that it is also partly imaginary. Not only did Gauguin muddle Place Lamartine with Place Victor Hugo, he also confused its vegetation. He wrote of lauriers - laurels - in flower. There are certain varieties of laurel which bloom in winter, but what he probably meant was Laurier-rose, or oleander, the flower "that speaks of love", which Vincent had painted in September. When he wrote this passage, in his mind Gauguin was walking through Vincent's paintings of these gardens which had hung in his bedroom.

Was there any more reality to that sinister blade, glittering in Vincent's hand? The indications were that it was also a product of his imagination. The knife had been employed as a weapon by both Jack the Ripper and his Parisian counterpart Prado in recent times, and their crimes had been widely reported. And that powerful gaze with which the crazed Vincent was subdued recalled the authority that the brothers Pianet exercised over the wild beasts in their menagerie, which had come to Arles earlier in the month.

It was true that Vincent was capable of acts of mild violence when deranged - kicking his nurse up the backside, for example. But - assuming the razor existed only in Gauguin's mind - why did he make up this grave accusation against his by then dead friend? The next paragraph of Gauguin's narrative supplied the motive:

"Was I negligent on this occasion? Should I have disarmed him and tried to calm him? I have often questioned my conscience about this, but I have never found anything to reproach myself with. Let him who will cast the first stone at me."

Obviously, Gauguin felt guilty; and he had examined his conscience. By the time he wrote those words Vincent had already been established as a great painter and a saint of art. If Gauguin had not turned on his heel, if he had returned to the Yellow House and soothed his friend, perhaps the disaster would have been averted - although the fate that was overtaking Vincent was probably inexorable. So, Gauguin supplied a very good reason for leaving. Nobody, after all, could blame him for refusing to spend the night under the same roof with an armed madman who had threatened to attack him. As it was, Gauguin had had enough. He spent the night in a hotel.

Vincent returned to the Yellow House, perhaps after he had completed the mission on which he was going out, according to Gauguin's first account. Possibly he posted his letter to Theo, or he went and had a drink, or both. Later in the evening, around 10.30pm to 11pm, he took the razor with which he sometimes shaved his beard and cut off his own left ear - or perhaps just the lower part of it (accounts differ). In this process, his auricular artery was severed, which caused blood to spurt and spray. As Gauguin remembered the scene the following day: "He must have taken some time to stop the flow of blood, for the day after there were a lot of wet towels lying about on the tiles in the lower two rooms. The blood had stained the two rooms and the little staircase that led up to our bedroom."

This indicated either that Vincent was in the studio, in the presence of his new painting, La Berceuse, when he mutilated himself - or that he had done so in the bedroom and then walked downstairs. After he had staunched the gore pumping from his head with the linen which he had bought so proudly for the Yellow House, he put the little amputated fragment of himself - having first washed it carefully, according to Gauguin - in an envelope of newspaper (perhaps that morning's L'Intransigeant).

Then he put on a hat, pulled right down on the injured side of his head - Gauguin recalled that it was a beret, perhaps Gauguin's own, left lying around after his abrupt departure. Vincent went out across Place Lamartine once more, through the gateway in the town wall, turned left and then took the second turning on the left, and walked to the brothel at No 1, Rue Bout d'Arles. There he asked the man on the door if he could see a girl named Rachel, and delivered his grisly package.

There are two slightly different accounts of how he did this. The following week the Forum républicain carried this item in its local news section: "Last Sunday at 11.30pm one Vincent Vaugogh painter, of Dutch origin, presented himself at the maison de tolérance no 1, asked for one Rachel, and gave her… his ear, saying, 'Guard this object very carefully.' Then he disappeared."

Gauguin told Bernard that Vincent gave more biblical-sounding instruction when he handed over his nasty package. "You will remember me, verily I tell you this."

Not surprisingly, Rachel fainted when she discovered what she had been given. Somehow, Vincent got home. He climbed the blood-spattered stairs, put a light in his window and fell - as he had before during these attacks - into a deep, deep sleep. While this drama was being played out a few hundred yards away in the Yellow House, Gauguin was tossing and turning in his hotel bed. He did not get to sleep until three and woke up later than usual, around 7.30am. When he was dressed, he walked over to Place Lamartine, perhaps intending to make amends for the row the night before, or at least to say goodbye in a more amicable fashion and collect his belongings. Possibly, he was a little concerned as to what had happened to Vincent on his own.

The sight that met his eyes as he approached the Yellow House was not reassuring. There was a great crowd of onlookers gathered in the square. "Near our house there were some gendarmes and a little gentleman in a bowler hat who was the commissioner of police." This was Joseph d'Ornano, the man who had been caricatured so cheerfully in Gauguin's sketchbook. Gauguin had no idea what had happened. But he must have been extremely alarmed; he no sooner appeared than he was arrested because the house "was full of blood". Presumably Gauguin came along before the police had entered the Yellow House, otherwise they would rapidly have established that Vincent was still alive. They had probably seen the evidence of carnage through the glass at the top of the studio door. This must have been a terrible moment for Gauguin. As he knew well, it was quite possible that Vincent had committed suicide; it was also possible that his death might look like murder. D'Ornano apparently assumed the worst.

Gauguin recalled:

"The gentleman in the bowler hat said to me straightaway, in a tone that was more than severe, 'What have you done to your comrade, Monsieur?'

'I don't know…'

'Oh, yes - you know very well… he is dead.'

I would never wish anyone such a moment, and it took me a long time to get my wits together and control the beating of my heart. Anger, indignation, grief, as well as shame at all these glances that were tearing my entire being to pieces, suffocated me, and I answered, stammeringly: 'All right, Monsieur, let us go upstairs. We can explain ourselves up there.' "

Perhaps Gauguin then produced his own key; at any rate, they climbed the stairs. Gauguin's starring role in the next part of the story made his account a little suspect:

"In the bed lay Vincent, rolled up in the sheets, curled up in a ball; he seemed lifeless. Gently, very gently, I touched the body, the heat of which showed that it was still alive. For me it was as if I had suddenly got back all my energy, all my spirit."

But perhaps he really had been the first to touch the body. "Then in a low voice I said to the police commissioner, 'Be kind enough, Monsieur, to awaken this man with great care, and if he asks for me tell him I have left for Paris; the sight of me might prove fatal to him.' I must own that from this moment the police commissioner was as reasonable as possible and intelligently sent for a doctor and a cab."

Vincent regained consciousness, though it does seem that Gauguin took care to remain out of his sight:

"Once awake, Vincent asked for his comrade, his pipe and his tobacco; he even thought of asking for the box that was downstairs and contained our money - a suspicion, I dare say! But I had already been through too much suffering to be troubled by that. Vincent was taken to a hospital where, as soon as he had arrived his mind began to wander again."

Gauguin was more specific, if not necessarily more accurate, when he gave his report to Bernard in Paris. He did not mention Vincent's worry that he had absconded with the household's petty cash, but he did describe what happened when Vincent was taken to the hospital, the Hôtel Dieu, on the other side of Arles: "His state is worse, he wants to sleep with the patients, chases the nurses, and washes himself in the coal bucket. That is to say, he continues the biblical mortifications."

Once he was released by the gendarmes, Gauguin sent a telegram to Theo telling him what had happened. The ear itself - or fragment of ear - was placed in a bottle and carefully handed over by the police to the doctors at the hospital, but far too late be of any use. So eventually it was thrown away. On Monday, December 24, Christmas Eve, Theo was sitting in his office in an exceptionally euphoric mood. He had already written to his middle sister, Elisabeth, or Lies, telling her of his engagement, when Gauguin's telegram arrived. Theo then wrote to his fiancée, Jo Bonger, who was staying with her brother in Paris. "Vincent is gravely ill," he scribbled at his desk. "I don't know what's wrong, but I shall have to go there as my presence is required. I'm so sorry that you will be upset because of me, when instead I would like to make you happy." He gave the letter to her brother.

Then he wrote to her again, enclosing some letters from his mother and his sister Wil and expressing the wish that Vincent, though very sick, might still recover. He caught a PLM express to the South, probably the 7.15pm train; Jo, who had a heavy cold, came to see him off at the Gare de Lyon. Next morning, Theo found Vincent in the hospital at Arles. The "people around him" - which meant Gauguin - told Theo of Vincent's "agitation", that he had for a few days been showing symptoms of madness, culminating in this "high fever" and self-mutilation.

"Will he remain insane?" Theo raised the question.

"The doctors think it is possible, but daren't yet say for certain. It should be apparent in a few days' time when he is rested; then we will see whether he is lucid again. He seemed all right for a few minutes when I was with him, but lapsed shortly afterwards into his brooding about philosophy and theology."

Vincent told Theo that in his delirium he had wandered over the fields of their childhood home, Zundert, and reminded his brother of how they had shared a little bedroom there, both boys' heads on one pillow:

"It was terribly sad being there, because from time to time all his grief would well up inside him, and he would try to weep, but couldn't. Poor fighter & poor, poor sufferer. Nothing can be done to relieve his anguish now, but it is deep and hard for him to bear. Had he once found someone to whom he could pour his heart out, it might never have come to this. In the next few days they will decide whether he is to be transferred to a special institution."

When Theo talked to Vincent about his engagement and asked if he approved of the plan, Vincent replied that, yes, he did, but marriage "ought not to be regarded as the main objective in life". Vincent, for all his loneliness, had doubts about conventional wedlock. Vincent asked for Gauguin "continually", "over and over". But Gauguin didn't go to visit him in the hospital that Christmas Day. He claimed that seeing him would upset Vincent; perhaps he shrank from the pleading to which he would certainly have been subjected. Theo left Arles on the night train to Paris on Christmas Day. Probably, Gauguin went with him, leaving so rapidly that he left several paintings and possessions in the Yellow House. He and Vincent never saw each other again. -- from the Arts Telegraph

THINGS I RECOMMEND AND REALLY ENJOY, AND HAVE ENJOYED FOR A LONG TIME

1> Liberty Mediterranee yogurt -- specifically the Peach/Passionfruit one. I've eaten this since I was a child. The best yogurt in the world.

2> Pilot Hi-Tecpoint V5 pens (black) -- I have used these since I was in Grade 9, and buy boxes of them whenever I spot them. I have them stashed around my house/office/car/bags, etc. My only complaint is that they tend to leak after being on an airplane. I have written the company about this to no avail. Still, they're worth it.

3> Sharpies -- like the above pens, but for writing on anything (envelopes, CDs) where you don't want your left-hand to smudge what it is you're writing.

4> Ecco shoes -- if you're unfortunate to have to wear business clothes each day, some good Ecco shoes sometimes make you forget you're not wearing warm, thick wool socks only. Speaking of which, Wigwam socks are the best in the world. If I have to stay in the clothing vein, Penguin makes things I like.

5> Subarus and Volvos

6> ...

In 1888, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin spent nine weeks living together in Arles. It was a time of astonishing creativity, culminating in a catastrophic falling-out. For his new book, Martin Gayford uncovered the true story of life in the Yellow House. On the evening of December 22 1888, Gauguin sat down to write a long, long letter to his friend, the French artist Claude Emile Schuffenecker - the longest communication he had sent to anybody since he arrived in Arles. Its copiousness suggested that he no longer had anyone to talk to closer to hand. Communications had broken down completely in the Yellow House.

Schuffenecker had replied, offering Gauguin hospitality in Paris, but Gauguin still wasn't quite ready to leave Arles. Gauguin thanked him for his offer; he wasn't coming straight away, but he might on an instant:

"I'm staying here for now, but I'm poised to leave at any moment. My situation here is painful; I owe much to [Theo] Van Gogh and Vincent and despite some discord I can't bear a grudge against a good heart who is ill and suffers and wants to see me."

Two considerations still restrained Gauguin from going. One was that he felt guilty about deserting Vincent. The other was that he was concerned about how Vincent's brother Theo might react if he did. "I need Van Gogh," he confided in Schuffenecker. The letter went on and on, quite unlike the brief notes Gauguin had sent Schuffenecker earlier in his stay. He was concerned that his sales through Theo had dried up. This was because the financial outlook was grim. His allegorical painting Human Miseries, which had not been sold, meant a lot to him; he would like Schuffenecker, who had a private income, to buy it (as he eventually did). He described the frame it should have: black with a yellow line on the inside edge.

"If I am able to leave," he announced, "in May with life assured in Martinique for 18 months I will almost be a happy mortal." He hoped to be followed there by his disciples, "all those who have loved and understood me". Gauguin elaborated his ideas of a better world in which men would live happily together under the tropical sun. But simultaneously he foresaw that his path in life would be lonely. In doing so he revealed how completely he had now absorbed Vincent's mental landscape. "Vincent," he noted, "sometimes calls me 'the man who has come from far away and will go far'."

Gauguin wrote on, for nine pages. Eventually, he closed his letter, even though, that "rainy evening", he could have gone on until morning. Under his signature, he did a little drawing of a memorial plaque he had invented for himself. It was a cartouche, bearing the date and the initials PGo, spelling out "pego", or "the prick".

Gauguin wrote Schuffenecker's address with a flourish, and then walked out into the rain to post the letter. He had missed the last collection of Saturday 22nd, which went at 10 o'clock, but his letter was in time for one of the first express trains on the following day, Sunday 23rd. That was the day on which the catastrophe, so long impending, finally occurred. Vincent continued to paint La Berceuse, his experimental canvas of a mother rocking a cradle. In an attempt to lure Gauguin into staying at the Yellow House, he reminded him that the great Degas had said he was "saving himself up for the Arlésiennes". If the women of Arles were good enough for Degas, surely the place had enough interest for Gauguin?

At some point he asked Gauguin point-blank if he was about to go. Gauguin described the encounter to Emile Bernard a few days later:

"I had to leave Arles, he was so bizarre I couldn't take it. He even said to me, 'Are you going to leave?' And when I said 'Yes' he tore this sentence from a newspaper and put it in my hand: 'The murderer took flight'."

These words were printed at the end of a small news item in the day's edition of L'Intransigeant. An unfortunate young man, one Albert Kalis, had been stabbed from behind while walking home at night. He had been taken to Bicêtre hospital in a desperate condition. "The murderer took flight."

The painters - according to Gauguin's much later recollection - proceeded to have their supper, cooked by Gauguin, as usual. Gauguin "bolted" his and went out to walk in Place Lamartine. He gave two quite different accounts of what happened next, and he was the only witness, because Vincent's memory of that night was very vague. He told the following story to Bernard, who narrated it to the critic Albert Aurier:

"Vincent ran after me - he was going out; it was night - I turned round because for some time he had been acting strangely. But I mistrusted him. Then he told me, 'You are silent, but I will also be silent.' "

Fifteen years later, Gauguin gave a more sensational version of the encounter:

"I felt I must go out alone and take the air along some paths that were bordered by flowering laurels. I had almost crossed the Place Victor Hugo when I heard behind me a well-known step, short, quick, irregular. I turned about on the instant as Vincent rushed towards me, an open razor in hand. My look at that moment must have had great power in it, for he stopped and, lowering his head, set off running towards the house."

This was vivid, but there were several indications that it is also partly imaginary. Not only did Gauguin muddle Place Lamartine with Place Victor Hugo, he also confused its vegetation. He wrote of lauriers - laurels - in flower. There are certain varieties of laurel which bloom in winter, but what he probably meant was Laurier-rose, or oleander, the flower "that speaks of love", which Vincent had painted in September. When he wrote this passage, in his mind Gauguin was walking through Vincent's paintings of these gardens which had hung in his bedroom.

Was there any more reality to that sinister blade, glittering in Vincent's hand? The indications were that it was also a product of his imagination. The knife had been employed as a weapon by both Jack the Ripper and his Parisian counterpart Prado in recent times, and their crimes had been widely reported. And that powerful gaze with which the crazed Vincent was subdued recalled the authority that the brothers Pianet exercised over the wild beasts in their menagerie, which had come to Arles earlier in the month.

It was true that Vincent was capable of acts of mild violence when deranged - kicking his nurse up the backside, for example. But - assuming the razor existed only in Gauguin's mind - why did he make up this grave accusation against his by then dead friend? The next paragraph of Gauguin's narrative supplied the motive:

"Was I negligent on this occasion? Should I have disarmed him and tried to calm him? I have often questioned my conscience about this, but I have never found anything to reproach myself with. Let him who will cast the first stone at me."

Obviously, Gauguin felt guilty; and he had examined his conscience. By the time he wrote those words Vincent had already been established as a great painter and a saint of art. If Gauguin had not turned on his heel, if he had returned to the Yellow House and soothed his friend, perhaps the disaster would have been averted - although the fate that was overtaking Vincent was probably inexorable. So, Gauguin supplied a very good reason for leaving. Nobody, after all, could blame him for refusing to spend the night under the same roof with an armed madman who had threatened to attack him. As it was, Gauguin had had enough. He spent the night in a hotel.

Vincent returned to the Yellow House, perhaps after he had completed the mission on which he was going out, according to Gauguin's first account. Possibly he posted his letter to Theo, or he went and had a drink, or both. Later in the evening, around 10.30pm to 11pm, he took the razor with which he sometimes shaved his beard and cut off his own left ear - or perhaps just the lower part of it (accounts differ). In this process, his auricular artery was severed, which caused blood to spurt and spray. As Gauguin remembered the scene the following day: "He must have taken some time to stop the flow of blood, for the day after there were a lot of wet towels lying about on the tiles in the lower two rooms. The blood had stained the two rooms and the little staircase that led up to our bedroom."

This indicated either that Vincent was in the studio, in the presence of his new painting, La Berceuse, when he mutilated himself - or that he had done so in the bedroom and then walked downstairs. After he had staunched the gore pumping from his head with the linen which he had bought so proudly for the Yellow House, he put the little amputated fragment of himself - having first washed it carefully, according to Gauguin - in an envelope of newspaper (perhaps that morning's L'Intransigeant).

Then he put on a hat, pulled right down on the injured side of his head - Gauguin recalled that it was a beret, perhaps Gauguin's own, left lying around after his abrupt departure. Vincent went out across Place Lamartine once more, through the gateway in the town wall, turned left and then took the second turning on the left, and walked to the brothel at No 1, Rue Bout d'Arles. There he asked the man on the door if he could see a girl named Rachel, and delivered his grisly package.

There are two slightly different accounts of how he did this. The following week the Forum républicain carried this item in its local news section: "Last Sunday at 11.30pm one Vincent Vaugogh painter, of Dutch origin, presented himself at the maison de tolérance no 1, asked for one Rachel, and gave her… his ear, saying, 'Guard this object very carefully.' Then he disappeared."

Gauguin told Bernard that Vincent gave more biblical-sounding instruction when he handed over his nasty package. "You will remember me, verily I tell you this."

Not surprisingly, Rachel fainted when she discovered what she had been given. Somehow, Vincent got home. He climbed the blood-spattered stairs, put a light in his window and fell - as he had before during these attacks - into a deep, deep sleep. While this drama was being played out a few hundred yards away in the Yellow House, Gauguin was tossing and turning in his hotel bed. He did not get to sleep until three and woke up later than usual, around 7.30am. When he was dressed, he walked over to Place Lamartine, perhaps intending to make amends for the row the night before, or at least to say goodbye in a more amicable fashion and collect his belongings. Possibly, he was a little concerned as to what had happened to Vincent on his own.

The sight that met his eyes as he approached the Yellow House was not reassuring. There was a great crowd of onlookers gathered in the square. "Near our house there were some gendarmes and a little gentleman in a bowler hat who was the commissioner of police." This was Joseph d'Ornano, the man who had been caricatured so cheerfully in Gauguin's sketchbook. Gauguin had no idea what had happened. But he must have been extremely alarmed; he no sooner appeared than he was arrested because the house "was full of blood". Presumably Gauguin came along before the police had entered the Yellow House, otherwise they would rapidly have established that Vincent was still alive. They had probably seen the evidence of carnage through the glass at the top of the studio door. This must have been a terrible moment for Gauguin. As he knew well, it was quite possible that Vincent had committed suicide; it was also possible that his death might look like murder. D'Ornano apparently assumed the worst.

Gauguin recalled:

"The gentleman in the bowler hat said to me straightaway, in a tone that was more than severe, 'What have you done to your comrade, Monsieur?'

'I don't know…'

'Oh, yes - you know very well… he is dead.'

I would never wish anyone such a moment, and it took me a long time to get my wits together and control the beating of my heart. Anger, indignation, grief, as well as shame at all these glances that were tearing my entire being to pieces, suffocated me, and I answered, stammeringly: 'All right, Monsieur, let us go upstairs. We can explain ourselves up there.' "

Perhaps Gauguin then produced his own key; at any rate, they climbed the stairs. Gauguin's starring role in the next part of the story made his account a little suspect:

"In the bed lay Vincent, rolled up in the sheets, curled up in a ball; he seemed lifeless. Gently, very gently, I touched the body, the heat of which showed that it was still alive. For me it was as if I had suddenly got back all my energy, all my spirit."

But perhaps he really had been the first to touch the body. "Then in a low voice I said to the police commissioner, 'Be kind enough, Monsieur, to awaken this man with great care, and if he asks for me tell him I have left for Paris; the sight of me might prove fatal to him.' I must own that from this moment the police commissioner was as reasonable as possible and intelligently sent for a doctor and a cab."

Vincent regained consciousness, though it does seem that Gauguin took care to remain out of his sight:

"Once awake, Vincent asked for his comrade, his pipe and his tobacco; he even thought of asking for the box that was downstairs and contained our money - a suspicion, I dare say! But I had already been through too much suffering to be troubled by that. Vincent was taken to a hospital where, as soon as he had arrived his mind began to wander again."

Gauguin was more specific, if not necessarily more accurate, when he gave his report to Bernard in Paris. He did not mention Vincent's worry that he had absconded with the household's petty cash, but he did describe what happened when Vincent was taken to the hospital, the Hôtel Dieu, on the other side of Arles: "His state is worse, he wants to sleep with the patients, chases the nurses, and washes himself in the coal bucket. That is to say, he continues the biblical mortifications."

Once he was released by the gendarmes, Gauguin sent a telegram to Theo telling him what had happened. The ear itself - or fragment of ear - was placed in a bottle and carefully handed over by the police to the doctors at the hospital, but far too late be of any use. So eventually it was thrown away. On Monday, December 24, Christmas Eve, Theo was sitting in his office in an exceptionally euphoric mood. He had already written to his middle sister, Elisabeth, or Lies, telling her of his engagement, when Gauguin's telegram arrived. Theo then wrote to his fiancée, Jo Bonger, who was staying with her brother in Paris. "Vincent is gravely ill," he scribbled at his desk. "I don't know what's wrong, but I shall have to go there as my presence is required. I'm so sorry that you will be upset because of me, when instead I would like to make you happy." He gave the letter to her brother.

Then he wrote to her again, enclosing some letters from his mother and his sister Wil and expressing the wish that Vincent, though very sick, might still recover. He caught a PLM express to the South, probably the 7.15pm train; Jo, who had a heavy cold, came to see him off at the Gare de Lyon. Next morning, Theo found Vincent in the hospital at Arles. The "people around him" - which meant Gauguin - told Theo of Vincent's "agitation", that he had for a few days been showing symptoms of madness, culminating in this "high fever" and self-mutilation.

"Will he remain insane?" Theo raised the question.

"The doctors think it is possible, but daren't yet say for certain. It should be apparent in a few days' time when he is rested; then we will see whether he is lucid again. He seemed all right for a few minutes when I was with him, but lapsed shortly afterwards into his brooding about philosophy and theology."

Vincent told Theo that in his delirium he had wandered over the fields of their childhood home, Zundert, and reminded his brother of how they had shared a little bedroom there, both boys' heads on one pillow:

"It was terribly sad being there, because from time to time all his grief would well up inside him, and he would try to weep, but couldn't. Poor fighter & poor, poor sufferer. Nothing can be done to relieve his anguish now, but it is deep and hard for him to bear. Had he once found someone to whom he could pour his heart out, it might never have come to this. In the next few days they will decide whether he is to be transferred to a special institution."

When Theo talked to Vincent about his engagement and asked if he approved of the plan, Vincent replied that, yes, he did, but marriage "ought not to be regarded as the main objective in life". Vincent, for all his loneliness, had doubts about conventional wedlock. Vincent asked for Gauguin "continually", "over and over". But Gauguin didn't go to visit him in the hospital that Christmas Day. He claimed that seeing him would upset Vincent; perhaps he shrank from the pleading to which he would certainly have been subjected. Theo left Arles on the night train to Paris on Christmas Day. Probably, Gauguin went with him, leaving so rapidly that he left several paintings and possessions in the Yellow House. He and Vincent never saw each other again. -- from the Arts Telegraph

THINGS I RECOMMEND AND REALLY ENJOY, AND HAVE ENJOYED FOR A LONG TIME

1> Liberty Mediterranee yogurt -- specifically the Peach/Passionfruit one. I've eaten this since I was a child. The best yogurt in the world.

2> Pilot Hi-Tecpoint V5 pens (black) -- I have used these since I was in Grade 9, and buy boxes of them whenever I spot them. I have them stashed around my house/office/car/bags, etc. My only complaint is that they tend to leak after being on an airplane. I have written the company about this to no avail. Still, they're worth it.

3> Sharpies -- like the above pens, but for writing on anything (envelopes, CDs) where you don't want your left-hand to smudge what it is you're writing.

4> Ecco shoes -- if you're unfortunate to have to wear business clothes each day, some good Ecco shoes sometimes make you forget you're not wearing warm, thick wool socks only. Speaking of which, Wigwam socks are the best in the world. If I have to stay in the clothing vein, Penguin makes things I like.

5> Subarus and Volvos

6> ...

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home