BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR?

Five years have passed since Madeleine Thien's first book, Simple Recipes -- a story collection that won several awards, including the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and the City of Vancouver Book Award -- perched her atop many Canadian critics' and editors' lists as a "writer to watch." In that time, her life has changed in significant ways. In 2002, she moved to Holland with her Dutch partner, Willem Atsma. She married him in 2004 and shortly afterward they moved to Quebec City, where Atsma researches human motor control for a company developing prosthetics.

Thien, now 31, has been brushing up her French, mentoring a young writer through the Quebec Writers' Federation and finishing a book. About her relationship with her husband, she says: "I think, in some ways, we are two of the same things. He's a scientist, a very creative person, who constantly has theoretical possibilities circling through his mind. So we can sit side by side on the couch, eating our spaghetti and thinking about wildly different things.

"On the other hand, he does have a streak of practicality that I don't have. Also, he looks into the world and understands it in a way that I don't yet." Since 2001, Thien has been working non-stop on her just-released first novel, Certainty. She estimates that she wrote "somewhere between eight and 10" drafts. She adds quickly: "But that seems reasonable, don't you think? It was five years, after all."

Given her many relocations, it may not be surprising that she has written a multi-layered narrative that leaps back and forth across the globe, over decades, from Vancouver to Southeast Asia, Australia and Holland. Before even being published, Certainty generated excited talk following foreign sales in nine countries, including Germany and the United Kingdom. These days, you're more likely to read Thien than to watch her. It's easy to see how the novel might appeal to so many different audiences. Certainty would be a tearjerker in any language. Thien seems perfectly attuned to the pain that resides in and defines her characters, many of whom are mourning the death of a loved one. As Alice Munro put it, there's an "emotional purity" to her writing. In fact, Thien drew from a major event in her own life to write about grieving. "While I was writing the novel, my mom died suddenly," she says, "so I started with bereavement, too."

This grieving also inspired the novel's title. "I was desperate for certainty about anything. I was also desperate to know how we go on, day after day, if we don't have it. "So the title is a question, and I think the characters circle around it as they live out their lives. Certainty ends up being a kind of faith -- in other people, in believing that something comes out of it all. It's hard to live without that kind of faith."

While researching the passages of Certainty that are set in the Second World War, Thien drew from the other side of her family. Like the father of one character in the book, Thien's grandfather was murdered by the Japanese in the province of Sabah, in East Malaysia. My grandfather was murdered after the war was over but before the town of Sandakan was liberated by Allied soldiers," she says. "I don't think anyone knows exactly how he died. I don't know if his body was ever found. My father once told me that all he remembers is his own father being led away by Japanese soldiers and then never returning."

In 2000, Thien spent two months in Malaysia and Thailand preparing for her novel. "I met a lot of family, aunts, uncles and cousins I'd never known before," she says, "and I met a lot of people who remembered what it was like to be a child or an adolescent during the war. But people didn't really have the words to describe that time, and they weren't accustomed to speaking about it. It was in the past, and the past was behind them.

"It was powerful and very moving. They would describe their experiences very briefly, with a single brushstroke, but the details were lost, forgotten or pushed away." Thien's plans for the future are fairly straightforward. "I want to travel again and I want to write another novel," she says. She misses Vancouver, including her lunches with friends, but has no immediate plans to return. As a reminder of home, she works at a rolltop desk that once belonged to her mother. "My computer is inside, so at the end of the day I just roll up the desk and close everything away."

She tries to keep her writing separate from the rest of her life, but it's not quite as simple as rolling the desk shut. "Writing can be such an absorbing and self-absorbed profession," she says. "I think that I have a tendency to be always thinking about other things, which can be a very irritating character trait. I think I'm getting better."

BY DAVID SEDARIS

For the past ten years or so, I’ve made it a habit to carry a small notebook in my front pocket. The model I favor is called the Europa, and I pull it out an average of ten times a day, jotting down grocery lists, observations, and little thoughts on how to make money, or torment people. The last page is always reserved for phone numbers, and the second to last I use for gift ideas. These are not things I might give to other people, but things that they might give to me: a shoehorn, for instance—always wanted one. The same goes for a pencil case, which, on the low end, probably costs no more than a doughnut.

I’ve also got ideas in the five-hundred-to-two-thousand-dollar range, though those tend to be more specific. This nineteenth-century portrait of a dog, for example. I’m not what you’d call a dog person, far from it, but this particular one—a whippet, I think—had alarmingly big nipples, huge, like bolts screwed halfway into her belly. More interesting was that she seemed aware of it. You could see it in her eyes as she turned to face the painter. “Oh, not now,” she appeared to be saying. “Have you no decency?”

I saw the portrait at the Portobello Road market in London, and though I petitioned, hard, for months, nobody bought it for me. I even tried initiating a pool, and offered to throw in a few hundred dollars of my own money, but still no one bit. In the end I gave the money to my boyfriend, Hugh, and had him buy it. Then I had him wrap it up, and offer it to me.

“What’s this for?” I asked.

And following the script he said, “Do I need a reason to give you a present?”

Then I said, “Awwwww.”

It never works the other way round, though. Ask Hugh what he wants for Christmas or his birthday and he’ll answer saying, “You tell me.”

“Well, isn’t there something you’ve had your eye on?”

“Maybe. Maybe not.”

Hugh thinks that lists are the easy way out, and says that if I really knew him I wouldn’t have to ask what he wanted. It’s not enough to search the shops; I have to search his soul as well. He turns gift-giving into a test, which I don’t think is fair at all. Were I the type to run out at the last minute, he might have a valid complaint, but I start my shopping months in advance. Plus I pay attention. If, say, in the middle of the summer, Hugh should mention that he’d like an electric fan, I’ll buy it that very day, and hide it in my gift cupboard. Come Christmas morning, he’ll open his present, and frown at it for a while before I say, “Don’t you remember? You said you were burning up, and would give anything for a little relief.”

That’s just a practical gift, though, a stocking stuffer. His main present is what I’m really after, and, knowing this, he offers no help whatsoever. Or, rather, he used to offer no help. It wasn’t until last year that he finally dropped a hint, and even then it was fairly cryptic. “Go out the front door, and turn right,” he said. “Then take a left and keep walking.”

He did not say “Stop before you reach the boulevard,” or “When you come to the Czech border you’ll know you’ve gone too far,” but he didn’t need to. I knew what he was talking about the moment I saw it. It was a human skeleton, the genuine article, hanging in the window of a medical bookstore. Hugh’s old drawing teacher used to have one, and though it had been ten years since he’d taken the woman’s class, I could suddenly recall him talking about it. “If I had a skeleton like Minerva’s . . .” he used to say. I don’t remember the rest of the sentence, as I’d always been sidetracked by the teacher’s name, Minerva. Sounds like a witch. There are things that one enjoys buying, and things that one doesn’t. Electronic equipment, for example—I hate shopping for stuff like that, no matter how happy it will make the recipient. I feel the same about gift certificates, and books about golf or investment strategies or how to lose twelve pounds by being yourself. I thought I would enjoy buying a human skeleton, but, looking through the shop window, I felt a familiar tug of disappointment. This had nothing to do with any moral considerations. I was fine with buying someone who’d been dead for a while; I just didn’t want to have to wrap him. Finding a box would be a pain, and then there’d be the paper, which would have to be attached in strips because no one sells rolls that wide. Between one thing and another, I was almost relieved when told that the skeleton was not for sale. “He’s our mascot,” the store manager said. “We couldn’t possibly get rid of him.”

In America this translates to “Make me an offer,” but in France people really mean it. There are shops in Paris where nothing is for sale, no matter how hard you beg. I think people get lonely. Their apartments become full, and, rather than rent a storage space, they take over a boutique. Then they sit there in the middle of it, gloating over their fine taste.

Being told that I couldn’t buy a skeleton was just what I needed to make me really want one. Maybe that was the problem all along—it was too easy: “Take a right, take a left, and keep walking.” It took the hunt out of it.

“Do you know anyone who will sell me their skeleton?” I asked, and the manager thought for a while. “Well,” she said, “I guess you could try looking on bulletin boards.” I don’t know what circles this woman runs in, but I have never in my life seen a skeleton advertised on a bulletin board. Used bicycles, yes, but no human bones, or even cartilage, for that matter. “Thank you for your help,” I said.

The baby was tempting because of its size—I could have wrapped it in a shoebox—but, ultimately, I went for the adult, which is three hundred years old and held together by a network of fine wires. There’s a latch in the center of the forehead, and removing the linchpin allows you to open the skull and either root around or hide things—drugs, say, or small pieces of jewelry. It’s not what one hopes for when thinking about an afterlife (“I’d like for my head to be used as a stash box”), but I didn’t let that bother me. I bought the skeleton the same way I buy most everything. It was just an arrangement of parts to me, no different from a lamp or a chest of drawers.

I didn’t think of it as a former person until Christmas Day, when Hugh opened the cardboard coffin. “If you don’t like the color we can bleach it,” I said. “Either that or exchange it for the baby.” I always like to offer a few alternatives, though in this case they were completely unnecessary. Hugh was beside himself—couldn’t have been happier. I assumed he’d be using the skeleton as a model, and was a little put off when, instead of taking it to his basement studio, he carried it into the bedroom, and hung it from the ceiling.

“Are you sure about this?” I asked.

The following morning, I reached under the bed for a discarded sock and found what I thought was a three-tiered earring. It looked like something you’d get at a crafts fair, not pretty, but definitely handmade, fashioned from what looked like petrified wood. I was just holding it to the side of my head when I thought, Hang on, this is an index finger. It must have fallen off while Hugh was hanging the skeleton. Then he or I or possibly his mother, who was in town for the holidays, accidentally kicked it under the bed.

I don’t think of myself as overly prissy, but it bothered me to find a finger on my bedroom floor. “If this thing is going to start shedding parts, you really should put it down in your studio,” I said to Hugh, who told me that it was his present and he’d keep it wherever he wanted to. Then he got out some wire and reattached the missing finger. As the days pass, I keep hoping that the skeleton will become invisible, but he hasn’t. Dangling between the dresser and the bedroom door, he is the last thing I see before falling asleep, and the first thing I see in the morning.

It’s funny how certain objects convey a message—my washer and dryer, for example. They can’t speak, of course, but whenever I pass them they remind me that I’m doing fairly well. “No more laundromat for you,” they hum. My stove, a downer, tells me every day that I can’t cook, and before I can defend myself my scale jumps in, shouting from the bathroom, “Well, he must be doing something—my numbers is off the charts.” The skeleton has a much more limited vocabulary, and says only one thing: “You are going to die.”

I’d always thought that I understood this, but lately I realize that what I call “understanding” is basically just fantasizing. I think about death all the time, but only in a romantic, self-serving way, beginning, most often, with my tragic illness, and ending with my funeral. I see my brother squatting beside my grave, so racked with guilt he’s unable to stand. “If only I’d paid him back that twenty-five thousand dollars I borrowed,” he says. I see Hugh, drying his eyes on the sleeve of his suit jacket, then crying even harder when he remembers I bought it for him. What I didn’t see were all the people who might celebrate my death, but that’s all changed with the skeleton, who assumes features at will.

One moment he’s an elderly Frenchwoman, the one I didn’t give my seat to on the bus. In my book, if you want to be treated like an old person, you have to look like one. That means no face-lift, no blond hair, and definitely no fishnet stockings. I think it’s a perfectly valid rule, but it wouldn’t have killed me to take her crutches into consideration. “I’m sorry,” I say, but before the words are out of my mouth the skeleton has morphed into a guy named Stew, who I shorted in a drug deal.

Stew and the Frenchwoman will be happy to see me go, and there are hundreds more in line behind them, some whom I can name, and others whom I managed to hurt and insult without a formal introduction. I hadn’t thought of these people in years, but that’s the skeleton’s cleverness. He gets into my head when I’m asleep, and picks through the muck at the bottom of my skull. “Why me?” I ask. “Hugh is lying in the very same bed—how come you don’t go after him?”

And the skeleton says, “You are going to die.”

“But I’m the one who found your finger.”

“You are going to die.”

I said to Hugh, “Are you sure you wouldn’t be happier with the baby?”

For the first few weeks, I heard the voice only when I was in the bedroom. Then it spread and took over the entire apartment. I’ll be sitting in my office, gossiping on the telephone, and the skeleton will cut in, sounding like an international operator. “You are going to die.”

I stretch out in the bathtub, soaking in fragrant oils while outside my window beggars are gathered like kittens upon the heating grates.

“You are going to die.”

In the kitchen, I throw away a perfectly good egg. In the closet, I put on a sweater that some half-blind child was paid ten sesame seeds to make. In the living room, I take out my notebook, and add a bust of Satan to the list of gifts I should like to receive.

“You are going to die. You are going to die. You are going to die.”

“Do you think you could alter that just a little?” I asked.

But he wouldn’t. Having been dead for three hundred years, there’s a lot the skeleton doesn’t understand; TV, for instance. “See,” I told him, “you just push this button and entertainment comes into your home.” He seemed impressed, and so I took it a step further: “I invented it myself, to bring comfort to the old and sick.”

“You are going to die.”

He was the same with the vacuum cleaner, even after I used the nozzle attachment to dust his skull. “You are going to die.”

And that’s when I broke down. “I’ll do anything you like,” I said. “I’ll make amends to the people I’ve hurt, I’ll bathe in rainwater, you name it, just please say something, anything else.”

The skeleton hesitated a moment. “You are going to be dead . . . someday,” he told me. And I put away the vacuum cleaner, thinking, Well, that’s a start.

FILM

Going to Extremes and Getting Personal in 'Mission: Impossible III'

By MANOHLA DARGIS NY TIMES

It would be a stretch to say that Tom Cruise needs a hit. What this guy needs is an intervention, someone who can help the star once known as Tom Terrific return to the glory days, when the only things most of us really knew about him came from the boilerplate continually recycled in glossy magazines, sealing him in a bubble of blandness and mystery. In those days, we didn't know that inside the world's biggest movie draw lurked a reckless couch-jumper and heartless amateur pharmacologist. All we saw was a billion-dollar smile and a performer who risked life and limb, everything but his own true self, for our movie-going pleasure.

Until the ascendancy of George Clooney, the multi-hyphenated sex bomb (he walks, he talks, he smiles and he thinks!), few stars seemed to work harder than Mr. Cruise. The embodiment of the 1990's extreme ethos, he could be counted on to hang tougher than anyone else, whether doing his own stunts, spending a couple of years in production with Stanley Kubrick, or, as he did on more than one occasion, rescuing a civilian. Recently, though, all that extremeness has seemed, well, too extreme. And you have to wonder if the real mission in his newest film isn't the search for the damsel in distress or the hunt for the supervillain, but the resurrection of a screen attraction who has, of late, seemed a bit of a freak.

Aptly named or not, "Mission: Impossible III" may emerge as Mr. Cruise's latest box-office triumph, but it won't do him any favors when it comes to his public persona, since it appears to have been explicitly tailored to reflect his personal life, or at least its outward face. As he has in the first two "Mission" films, Mr. Cruise plays Ethan Hunt, a member of a stealth government agency, the Impossible Mission Force, who circumnavigates the world, blowing stuff up to wage battle against all manner of wickedness. Again he racks up miles (Berlin, Rome, Shanghai) and lights a few fuses, including that of a humorously decadent arms dealer, Owen Davian (Philip Seymour Hoffman), but this time he also has a main squeeze, Julia (the welcome if badly used Michelle Monaghan).

The overlap between a star's private and public selves can add frisson to the screen, especially when the luminaries are Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, but it can prove deleterious, especially when it reeks of public relations. "Mission: Impossible III" opens in medias res with a screaming match between Ethan, who's actually doing all the screaming, and Davian, who's holding a gun on a woman. "I am going to kill you!" Ethan shouts, limbs bound and tendons jumping. Alas, before that happens, the director J. J. Abrams, who wrote the script with Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci, backtracks to an engagement party, where, tendons at ease and smile blasting, Ethan is playing the aggressively jubilant fiancé, all but shrieking, "I am going to marry her!"

Viewer, he does. In between communiqués with his agency superiors (Billy Crudup, Laurence Fishburne), a rescue mission (hence, Keri Russell from "Felicity") and pyrotechnic larks with his newest team (Ving Rhames, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, the decorative Hong Kong transplant Maggie Q), Ethan settles into domesticity, an endeavor interrupted when Julia is kidnapped by a malevolently aggrieved Davian. Mr. Hoffman isn't given all that much to do in the film, but what he does is choice. With a sneer in his voice and a lazy slouch that telegraphs world-weariness of the most misanthropic kind, he creates an ice-blooded creature who seems as if he would like nothing better than to destroy the earth, and with as much human suffering as possible. The too-few scenes of Mr. Hoffman going directly up against Mr. Cruise are particularly tasty. Mr. Hoffman enlivens "Mission: Impossible III," which otherwise droops, done in both by the maudlin romance and by Mr. Abrams's inability to adapt his small-screen talent — evident in his capacity as the television auteur behind "Alias" and "Lost" — to a larger canvas. The action remains consistently lackluster despite the usual frantic editing and several stunts that should pop off the screen. Typical of Mr. Abrams's difficulty in getting a grip on big-screen action is an extravagant feat that finds Ethan BASE-jumping from one high-rise to another, a stunt that, because it was filmed mostly in extreme long shot and at night, might as well have been executed by Spider-Man's computer-generated avatar. A daytime battle on a bridge works better, largely because you can see Mr. Cruise panting amid the bullets and mayhem.

Although he slams into stationary objects with his customary zeal, the usually dependable Mr. Cruise is off his game here, sabotaged by the misguided attempt to shade his character with gray. The domestication of Ethan Hunt may have seemed like a good idea, a humanizing touch, perhaps, but it only bogs down the action. Worse, it turns a perfectly good franchise into a seriously strange vanity project, as the simpering brunette is swept into a new world by a dashing operative for a clandestine organization. Much like the man playing him, Ethan works only if you don't know anything about what makes him tick. Once upon a Hollywood time, the studios carefully protected their stars from the press and the public. Now the impossible mission, it seems, is protecting them from themselves.

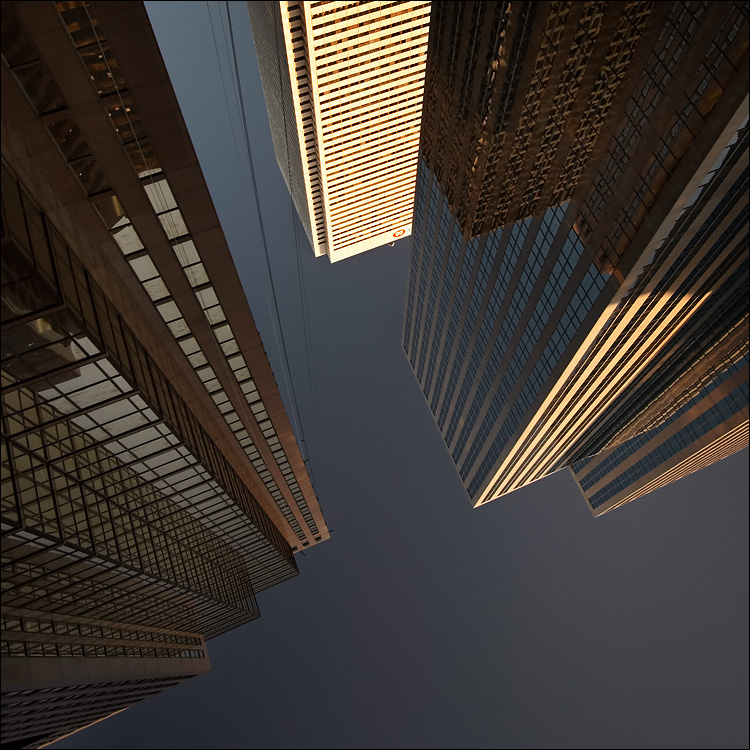

Toronto, near my work

Titles of Songs I Could Credibly Write If I Became a Rap Star. BY GREG HOWARD

Ain't Nothin' but a G Thang, Although I Usually Go by "Greg," to Be Honest

Mama Said Have Some Milk and Cookies

Bitches and Hos (I Have Neither/Nor)

I Know Someone Who Has a Friend of a Friend Who's Chillin' on Death Row

Ready 2 Take a Nap

Roll Me a Blunt (Now What Does That Mean Again?)

The Best Tastee-Freezes Are in My Hood

YO Gangsta (Do You Know How to Get to Napa Valley? I Appear to Be Lost)

I Like Medium-Sized Butts ... I Mean, It's Great If They Have Some Dimension but Let's Not Get Carried Away, but on the Other Hand It's No Good When the Legs Just Shoot Straight Up to the Hips and There's Nothing Else There, I Hate That

Smack My Fax Up

INTERESTING

Canadians are not responsible for making sure their house guests don't drive away drunk, the Supreme Court of Canada said on Friday. The top court ruled that Zoe Childs cannot sue the people who let a known drunk leave their party in Ottawa and drive away in 1999. The court unanimously ruled against her suit for damages. Childs was left paralyzed when Desmond Desormeaux slammed his car into the one she was riding in. Her boyfriend was killed in the collision. Desormeaux, an alcoholic with previous drunk-driving convictions, had just left a New Year's Eve house party and had more than twice the legal limit of alcohol in his system.

He was jailed in 2000 for 10 years, in what was thought to be the country's longest sentence for impaired driving causing death. After the criminal case was completed, Childs filed suit against Desormeaux and against the hosts of the party. The case against the hosts reached the top court earlier this year, when her lawyer, Barry Laushway. argued that the crash was predictable, and that the hosts should have seen it coming because they knew Desormeaux was unfit to drive.

"Whatever the test is, we say it has to be more than what these people did — which is absolutely nothing," he said. Proponents of tougher drunk-driving laws, including Mothers Against Drunk Driving, have said private party hosts should meet the same standards that apply to bars, which are responsible for drinkers. Jeremy Debeer, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, wonders how far people would have to go to prevent their guests from drinking and driving should Childs win her case.

"Do they have to ask their guest if they're OK to drive?" he asked. "Do they have to offer to call a cab? Actually call a cab? Physically restrain a guest from leaving? Call the police after the guest has left?"

"There's a whole spectrum in terms of the standard we're going to hold social hosts to."

Eric Williams, the lawyer for the hosts, argued in court that his clients had not served Desormeaux the alcohol and could not have known how much he had consumed or exactly how drunk he was when he drove off. Williams also argued that a finding of social host liability in the case could unfairly burden any Canadian who has friends over to share a drink. Lawyers for the Insurance Board of Canada made similar arguments in court, predicting a spike in both lawsuits and insurance premiums if the Supreme Court rules in Childs' favour.

Five years have passed since Madeleine Thien's first book, Simple Recipes -- a story collection that won several awards, including the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and the City of Vancouver Book Award -- perched her atop many Canadian critics' and editors' lists as a "writer to watch." In that time, her life has changed in significant ways. In 2002, she moved to Holland with her Dutch partner, Willem Atsma. She married him in 2004 and shortly afterward they moved to Quebec City, where Atsma researches human motor control for a company developing prosthetics.

Thien, now 31, has been brushing up her French, mentoring a young writer through the Quebec Writers' Federation and finishing a book. About her relationship with her husband, she says: "I think, in some ways, we are two of the same things. He's a scientist, a very creative person, who constantly has theoretical possibilities circling through his mind. So we can sit side by side on the couch, eating our spaghetti and thinking about wildly different things.

"On the other hand, he does have a streak of practicality that I don't have. Also, he looks into the world and understands it in a way that I don't yet." Since 2001, Thien has been working non-stop on her just-released first novel, Certainty. She estimates that she wrote "somewhere between eight and 10" drafts. She adds quickly: "But that seems reasonable, don't you think? It was five years, after all."

Given her many relocations, it may not be surprising that she has written a multi-layered narrative that leaps back and forth across the globe, over decades, from Vancouver to Southeast Asia, Australia and Holland. Before even being published, Certainty generated excited talk following foreign sales in nine countries, including Germany and the United Kingdom. These days, you're more likely to read Thien than to watch her. It's easy to see how the novel might appeal to so many different audiences. Certainty would be a tearjerker in any language. Thien seems perfectly attuned to the pain that resides in and defines her characters, many of whom are mourning the death of a loved one. As Alice Munro put it, there's an "emotional purity" to her writing. In fact, Thien drew from a major event in her own life to write about grieving. "While I was writing the novel, my mom died suddenly," she says, "so I started with bereavement, too."

This grieving also inspired the novel's title. "I was desperate for certainty about anything. I was also desperate to know how we go on, day after day, if we don't have it. "So the title is a question, and I think the characters circle around it as they live out their lives. Certainty ends up being a kind of faith -- in other people, in believing that something comes out of it all. It's hard to live without that kind of faith."

While researching the passages of Certainty that are set in the Second World War, Thien drew from the other side of her family. Like the father of one character in the book, Thien's grandfather was murdered by the Japanese in the province of Sabah, in East Malaysia. My grandfather was murdered after the war was over but before the town of Sandakan was liberated by Allied soldiers," she says. "I don't think anyone knows exactly how he died. I don't know if his body was ever found. My father once told me that all he remembers is his own father being led away by Japanese soldiers and then never returning."

In 2000, Thien spent two months in Malaysia and Thailand preparing for her novel. "I met a lot of family, aunts, uncles and cousins I'd never known before," she says, "and I met a lot of people who remembered what it was like to be a child or an adolescent during the war. But people didn't really have the words to describe that time, and they weren't accustomed to speaking about it. It was in the past, and the past was behind them.

"It was powerful and very moving. They would describe their experiences very briefly, with a single brushstroke, but the details were lost, forgotten or pushed away." Thien's plans for the future are fairly straightforward. "I want to travel again and I want to write another novel," she says. She misses Vancouver, including her lunches with friends, but has no immediate plans to return. As a reminder of home, she works at a rolltop desk that once belonged to her mother. "My computer is inside, so at the end of the day I just roll up the desk and close everything away."

She tries to keep her writing separate from the rest of her life, but it's not quite as simple as rolling the desk shut. "Writing can be such an absorbing and self-absorbed profession," she says. "I think that I have a tendency to be always thinking about other things, which can be a very irritating character trait. I think I'm getting better."

BY DAVID SEDARIS

For the past ten years or so, I’ve made it a habit to carry a small notebook in my front pocket. The model I favor is called the Europa, and I pull it out an average of ten times a day, jotting down grocery lists, observations, and little thoughts on how to make money, or torment people. The last page is always reserved for phone numbers, and the second to last I use for gift ideas. These are not things I might give to other people, but things that they might give to me: a shoehorn, for instance—always wanted one. The same goes for a pencil case, which, on the low end, probably costs no more than a doughnut.

I’ve also got ideas in the five-hundred-to-two-thousand-dollar range, though those tend to be more specific. This nineteenth-century portrait of a dog, for example. I’m not what you’d call a dog person, far from it, but this particular one—a whippet, I think—had alarmingly big nipples, huge, like bolts screwed halfway into her belly. More interesting was that she seemed aware of it. You could see it in her eyes as she turned to face the painter. “Oh, not now,” she appeared to be saying. “Have you no decency?”

I saw the portrait at the Portobello Road market in London, and though I petitioned, hard, for months, nobody bought it for me. I even tried initiating a pool, and offered to throw in a few hundred dollars of my own money, but still no one bit. In the end I gave the money to my boyfriend, Hugh, and had him buy it. Then I had him wrap it up, and offer it to me.

“What’s this for?” I asked.

And following the script he said, “Do I need a reason to give you a present?”

Then I said, “Awwwww.”

It never works the other way round, though. Ask Hugh what he wants for Christmas or his birthday and he’ll answer saying, “You tell me.”

“Well, isn’t there something you’ve had your eye on?”

“Maybe. Maybe not.”

Hugh thinks that lists are the easy way out, and says that if I really knew him I wouldn’t have to ask what he wanted. It’s not enough to search the shops; I have to search his soul as well. He turns gift-giving into a test, which I don’t think is fair at all. Were I the type to run out at the last minute, he might have a valid complaint, but I start my shopping months in advance. Plus I pay attention. If, say, in the middle of the summer, Hugh should mention that he’d like an electric fan, I’ll buy it that very day, and hide it in my gift cupboard. Come Christmas morning, he’ll open his present, and frown at it for a while before I say, “Don’t you remember? You said you were burning up, and would give anything for a little relief.”

That’s just a practical gift, though, a stocking stuffer. His main present is what I’m really after, and, knowing this, he offers no help whatsoever. Or, rather, he used to offer no help. It wasn’t until last year that he finally dropped a hint, and even then it was fairly cryptic. “Go out the front door, and turn right,” he said. “Then take a left and keep walking.”

He did not say “Stop before you reach the boulevard,” or “When you come to the Czech border you’ll know you’ve gone too far,” but he didn’t need to. I knew what he was talking about the moment I saw it. It was a human skeleton, the genuine article, hanging in the window of a medical bookstore. Hugh’s old drawing teacher used to have one, and though it had been ten years since he’d taken the woman’s class, I could suddenly recall him talking about it. “If I had a skeleton like Minerva’s . . .” he used to say. I don’t remember the rest of the sentence, as I’d always been sidetracked by the teacher’s name, Minerva. Sounds like a witch. There are things that one enjoys buying, and things that one doesn’t. Electronic equipment, for example—I hate shopping for stuff like that, no matter how happy it will make the recipient. I feel the same about gift certificates, and books about golf or investment strategies or how to lose twelve pounds by being yourself. I thought I would enjoy buying a human skeleton, but, looking through the shop window, I felt a familiar tug of disappointment. This had nothing to do with any moral considerations. I was fine with buying someone who’d been dead for a while; I just didn’t want to have to wrap him. Finding a box would be a pain, and then there’d be the paper, which would have to be attached in strips because no one sells rolls that wide. Between one thing and another, I was almost relieved when told that the skeleton was not for sale. “He’s our mascot,” the store manager said. “We couldn’t possibly get rid of him.”

In America this translates to “Make me an offer,” but in France people really mean it. There are shops in Paris where nothing is for sale, no matter how hard you beg. I think people get lonely. Their apartments become full, and, rather than rent a storage space, they take over a boutique. Then they sit there in the middle of it, gloating over their fine taste.

Being told that I couldn’t buy a skeleton was just what I needed to make me really want one. Maybe that was the problem all along—it was too easy: “Take a right, take a left, and keep walking.” It took the hunt out of it.

“Do you know anyone who will sell me their skeleton?” I asked, and the manager thought for a while. “Well,” she said, “I guess you could try looking on bulletin boards.” I don’t know what circles this woman runs in, but I have never in my life seen a skeleton advertised on a bulletin board. Used bicycles, yes, but no human bones, or even cartilage, for that matter. “Thank you for your help,” I said.

The baby was tempting because of its size—I could have wrapped it in a shoebox—but, ultimately, I went for the adult, which is three hundred years old and held together by a network of fine wires. There’s a latch in the center of the forehead, and removing the linchpin allows you to open the skull and either root around or hide things—drugs, say, or small pieces of jewelry. It’s not what one hopes for when thinking about an afterlife (“I’d like for my head to be used as a stash box”), but I didn’t let that bother me. I bought the skeleton the same way I buy most everything. It was just an arrangement of parts to me, no different from a lamp or a chest of drawers.

I didn’t think of it as a former person until Christmas Day, when Hugh opened the cardboard coffin. “If you don’t like the color we can bleach it,” I said. “Either that or exchange it for the baby.” I always like to offer a few alternatives, though in this case they were completely unnecessary. Hugh was beside himself—couldn’t have been happier. I assumed he’d be using the skeleton as a model, and was a little put off when, instead of taking it to his basement studio, he carried it into the bedroom, and hung it from the ceiling.

“Are you sure about this?” I asked.

The following morning, I reached under the bed for a discarded sock and found what I thought was a three-tiered earring. It looked like something you’d get at a crafts fair, not pretty, but definitely handmade, fashioned from what looked like petrified wood. I was just holding it to the side of my head when I thought, Hang on, this is an index finger. It must have fallen off while Hugh was hanging the skeleton. Then he or I or possibly his mother, who was in town for the holidays, accidentally kicked it under the bed.

I don’t think of myself as overly prissy, but it bothered me to find a finger on my bedroom floor. “If this thing is going to start shedding parts, you really should put it down in your studio,” I said to Hugh, who told me that it was his present and he’d keep it wherever he wanted to. Then he got out some wire and reattached the missing finger. As the days pass, I keep hoping that the skeleton will become invisible, but he hasn’t. Dangling between the dresser and the bedroom door, he is the last thing I see before falling asleep, and the first thing I see in the morning.

It’s funny how certain objects convey a message—my washer and dryer, for example. They can’t speak, of course, but whenever I pass them they remind me that I’m doing fairly well. “No more laundromat for you,” they hum. My stove, a downer, tells me every day that I can’t cook, and before I can defend myself my scale jumps in, shouting from the bathroom, “Well, he must be doing something—my numbers is off the charts.” The skeleton has a much more limited vocabulary, and says only one thing: “You are going to die.”

I’d always thought that I understood this, but lately I realize that what I call “understanding” is basically just fantasizing. I think about death all the time, but only in a romantic, self-serving way, beginning, most often, with my tragic illness, and ending with my funeral. I see my brother squatting beside my grave, so racked with guilt he’s unable to stand. “If only I’d paid him back that twenty-five thousand dollars I borrowed,” he says. I see Hugh, drying his eyes on the sleeve of his suit jacket, then crying even harder when he remembers I bought it for him. What I didn’t see were all the people who might celebrate my death, but that’s all changed with the skeleton, who assumes features at will.

One moment he’s an elderly Frenchwoman, the one I didn’t give my seat to on the bus. In my book, if you want to be treated like an old person, you have to look like one. That means no face-lift, no blond hair, and definitely no fishnet stockings. I think it’s a perfectly valid rule, but it wouldn’t have killed me to take her crutches into consideration. “I’m sorry,” I say, but before the words are out of my mouth the skeleton has morphed into a guy named Stew, who I shorted in a drug deal.

Stew and the Frenchwoman will be happy to see me go, and there are hundreds more in line behind them, some whom I can name, and others whom I managed to hurt and insult without a formal introduction. I hadn’t thought of these people in years, but that’s the skeleton’s cleverness. He gets into my head when I’m asleep, and picks through the muck at the bottom of my skull. “Why me?” I ask. “Hugh is lying in the very same bed—how come you don’t go after him?”

And the skeleton says, “You are going to die.”

“But I’m the one who found your finger.”

“You are going to die.”

I said to Hugh, “Are you sure you wouldn’t be happier with the baby?”

For the first few weeks, I heard the voice only when I was in the bedroom. Then it spread and took over the entire apartment. I’ll be sitting in my office, gossiping on the telephone, and the skeleton will cut in, sounding like an international operator. “You are going to die.”

I stretch out in the bathtub, soaking in fragrant oils while outside my window beggars are gathered like kittens upon the heating grates.

“You are going to die.”

In the kitchen, I throw away a perfectly good egg. In the closet, I put on a sweater that some half-blind child was paid ten sesame seeds to make. In the living room, I take out my notebook, and add a bust of Satan to the list of gifts I should like to receive.

“You are going to die. You are going to die. You are going to die.”

“Do you think you could alter that just a little?” I asked.

But he wouldn’t. Having been dead for three hundred years, there’s a lot the skeleton doesn’t understand; TV, for instance. “See,” I told him, “you just push this button and entertainment comes into your home.” He seemed impressed, and so I took it a step further: “I invented it myself, to bring comfort to the old and sick.”

“You are going to die.”

He was the same with the vacuum cleaner, even after I used the nozzle attachment to dust his skull. “You are going to die.”

And that’s when I broke down. “I’ll do anything you like,” I said. “I’ll make amends to the people I’ve hurt, I’ll bathe in rainwater, you name it, just please say something, anything else.”

The skeleton hesitated a moment. “You are going to be dead . . . someday,” he told me. And I put away the vacuum cleaner, thinking, Well, that’s a start.

FILM

Going to Extremes and Getting Personal in 'Mission: Impossible III'

By MANOHLA DARGIS NY TIMES

It would be a stretch to say that Tom Cruise needs a hit. What this guy needs is an intervention, someone who can help the star once known as Tom Terrific return to the glory days, when the only things most of us really knew about him came from the boilerplate continually recycled in glossy magazines, sealing him in a bubble of blandness and mystery. In those days, we didn't know that inside the world's biggest movie draw lurked a reckless couch-jumper and heartless amateur pharmacologist. All we saw was a billion-dollar smile and a performer who risked life and limb, everything but his own true self, for our movie-going pleasure.

Until the ascendancy of George Clooney, the multi-hyphenated sex bomb (he walks, he talks, he smiles and he thinks!), few stars seemed to work harder than Mr. Cruise. The embodiment of the 1990's extreme ethos, he could be counted on to hang tougher than anyone else, whether doing his own stunts, spending a couple of years in production with Stanley Kubrick, or, as he did on more than one occasion, rescuing a civilian. Recently, though, all that extremeness has seemed, well, too extreme. And you have to wonder if the real mission in his newest film isn't the search for the damsel in distress or the hunt for the supervillain, but the resurrection of a screen attraction who has, of late, seemed a bit of a freak.

Aptly named or not, "Mission: Impossible III" may emerge as Mr. Cruise's latest box-office triumph, but it won't do him any favors when it comes to his public persona, since it appears to have been explicitly tailored to reflect his personal life, or at least its outward face. As he has in the first two "Mission" films, Mr. Cruise plays Ethan Hunt, a member of a stealth government agency, the Impossible Mission Force, who circumnavigates the world, blowing stuff up to wage battle against all manner of wickedness. Again he racks up miles (Berlin, Rome, Shanghai) and lights a few fuses, including that of a humorously decadent arms dealer, Owen Davian (Philip Seymour Hoffman), but this time he also has a main squeeze, Julia (the welcome if badly used Michelle Monaghan).

The overlap between a star's private and public selves can add frisson to the screen, especially when the luminaries are Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, but it can prove deleterious, especially when it reeks of public relations. "Mission: Impossible III" opens in medias res with a screaming match between Ethan, who's actually doing all the screaming, and Davian, who's holding a gun on a woman. "I am going to kill you!" Ethan shouts, limbs bound and tendons jumping. Alas, before that happens, the director J. J. Abrams, who wrote the script with Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci, backtracks to an engagement party, where, tendons at ease and smile blasting, Ethan is playing the aggressively jubilant fiancé, all but shrieking, "I am going to marry her!"

Viewer, he does. In between communiqués with his agency superiors (Billy Crudup, Laurence Fishburne), a rescue mission (hence, Keri Russell from "Felicity") and pyrotechnic larks with his newest team (Ving Rhames, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, the decorative Hong Kong transplant Maggie Q), Ethan settles into domesticity, an endeavor interrupted when Julia is kidnapped by a malevolently aggrieved Davian. Mr. Hoffman isn't given all that much to do in the film, but what he does is choice. With a sneer in his voice and a lazy slouch that telegraphs world-weariness of the most misanthropic kind, he creates an ice-blooded creature who seems as if he would like nothing better than to destroy the earth, and with as much human suffering as possible. The too-few scenes of Mr. Hoffman going directly up against Mr. Cruise are particularly tasty. Mr. Hoffman enlivens "Mission: Impossible III," which otherwise droops, done in both by the maudlin romance and by Mr. Abrams's inability to adapt his small-screen talent — evident in his capacity as the television auteur behind "Alias" and "Lost" — to a larger canvas. The action remains consistently lackluster despite the usual frantic editing and several stunts that should pop off the screen. Typical of Mr. Abrams's difficulty in getting a grip on big-screen action is an extravagant feat that finds Ethan BASE-jumping from one high-rise to another, a stunt that, because it was filmed mostly in extreme long shot and at night, might as well have been executed by Spider-Man's computer-generated avatar. A daytime battle on a bridge works better, largely because you can see Mr. Cruise panting amid the bullets and mayhem.

Although he slams into stationary objects with his customary zeal, the usually dependable Mr. Cruise is off his game here, sabotaged by the misguided attempt to shade his character with gray. The domestication of Ethan Hunt may have seemed like a good idea, a humanizing touch, perhaps, but it only bogs down the action. Worse, it turns a perfectly good franchise into a seriously strange vanity project, as the simpering brunette is swept into a new world by a dashing operative for a clandestine organization. Much like the man playing him, Ethan works only if you don't know anything about what makes him tick. Once upon a Hollywood time, the studios carefully protected their stars from the press and the public. Now the impossible mission, it seems, is protecting them from themselves.

Toronto, near my work

Titles of Songs I Could Credibly Write If I Became a Rap Star. BY GREG HOWARD

Ain't Nothin' but a G Thang, Although I Usually Go by "Greg," to Be Honest

Mama Said Have Some Milk and Cookies

Bitches and Hos (I Have Neither/Nor)

I Know Someone Who Has a Friend of a Friend Who's Chillin' on Death Row

Ready 2 Take a Nap

Roll Me a Blunt (Now What Does That Mean Again?)

The Best Tastee-Freezes Are in My Hood

YO Gangsta (Do You Know How to Get to Napa Valley? I Appear to Be Lost)

I Like Medium-Sized Butts ... I Mean, It's Great If They Have Some Dimension but Let's Not Get Carried Away, but on the Other Hand It's No Good When the Legs Just Shoot Straight Up to the Hips and There's Nothing Else There, I Hate That

Smack My Fax Up

INTERESTING

Canadians are not responsible for making sure their house guests don't drive away drunk, the Supreme Court of Canada said on Friday. The top court ruled that Zoe Childs cannot sue the people who let a known drunk leave their party in Ottawa and drive away in 1999. The court unanimously ruled against her suit for damages. Childs was left paralyzed when Desmond Desormeaux slammed his car into the one she was riding in. Her boyfriend was killed in the collision. Desormeaux, an alcoholic with previous drunk-driving convictions, had just left a New Year's Eve house party and had more than twice the legal limit of alcohol in his system.

He was jailed in 2000 for 10 years, in what was thought to be the country's longest sentence for impaired driving causing death. After the criminal case was completed, Childs filed suit against Desormeaux and against the hosts of the party. The case against the hosts reached the top court earlier this year, when her lawyer, Barry Laushway. argued that the crash was predictable, and that the hosts should have seen it coming because they knew Desormeaux was unfit to drive.

"Whatever the test is, we say it has to be more than what these people did — which is absolutely nothing," he said. Proponents of tougher drunk-driving laws, including Mothers Against Drunk Driving, have said private party hosts should meet the same standards that apply to bars, which are responsible for drinkers. Jeremy Debeer, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, wonders how far people would have to go to prevent their guests from drinking and driving should Childs win her case.

"Do they have to ask their guest if they're OK to drive?" he asked. "Do they have to offer to call a cab? Actually call a cab? Physically restrain a guest from leaving? Call the police after the guest has left?"

"There's a whole spectrum in terms of the standard we're going to hold social hosts to."

Eric Williams, the lawyer for the hosts, argued in court that his clients had not served Desormeaux the alcohol and could not have known how much he had consumed or exactly how drunk he was when he drove off. Williams also argued that a finding of social host liability in the case could unfairly burden any Canadian who has friends over to share a drink. Lawyers for the Insurance Board of Canada made similar arguments in court, predicting a spike in both lawsuits and insurance premiums if the Supreme Court rules in Childs' favour.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home