MUSIC: APPRECIATIONS

from Rolling Stone

Elvis Presley

Out of Tupelo, Mississippi, out of Memphis, Tennessee, came this green, sharkskin-suited girl chaser, wearing eye shadow -- a trucker-dandy white boy who must have risked his hide to act so black and dress so gay. This wasn't New York or even New Orleans; this was Memphis in the Fifties. This was punk rock. This was revolt. Elvis changed everything -- musically, sexually, politically. In Elvis, you had the whole lot; it's all there in that elastic voice and body. As he changed shape, so did the world: He was a Fifties-style icon who was what the Sixties were capable of, and then suddenly not. In the Seventies, he turned celebrity into a blood sport, but interestingly, the more he fell to Earth, the more godlike he became to his fans. His last performances showcase a voice even bigger than his gut, where you cry real tears as the music messiah sings his tired heart out, turning casino into temple. In Elvis, you have the blueprint for rock & roll: The highness -- the gospel highs. The mud -- the Delta mud, the blues. Sexual liberation. Controversy. Changing the way people feel about the world. It's all there with Elvis.

I was barely conscious when I saw the '68 comeback special, at eight years old -- which was probably an advantage. I hadn't the critical faculties to divide the different Elvises into different categories or sort through the contradictions. Pretty much everything I want from guitar, bass and drums was present: a performer annoyed by the distance from his audience; a persona that made a prism of fame's wide-angle lens; a sexuality matched only by a thirst for God's instruction. But it's that elastic spastic dance that is the most difficult to explain -- hips that swivel from Europe to Africa, which is the whole point of America, I guess. For an Irish boy, the voice might have explained the sexiness of the U.S.A., but the dance explained the energy of this new world about to boil over and scald the rest of us with new ideas on race, religion, fashion, love and peace. These were ideas bigger than the man who would break the ice for them, ideas that would later confound the man who took the Anglo-Saxon stiff upper lip and curled it forever. He was "Elvis the Pelvis," with one hand on the blues terminal and the other on the gospel, which is the essence of rock & roll, a lightning flash running along his spine, electroshock therapy for a generation about to refuse numbness, both male and female, black and white.

I recently met with Coretta Scott King, John Lewis and some of the other leaders of the American civil-rights movement, and they reminded me of the cultural apartheid rock & roll was up against. I think the hill they climbed would have been much steeper were it not for the racial inroads black music was making on white pop culture. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival were all introduced to the blues through Elvis. He was already doing what the civil-rights movement was demanding: breaking down barriers. You don't think of Elvis as political, but that is politics: changing the way people see the world.

In the Eighties, U2 went to Memphis, to Sun Studio -- the scene of rock & roll's big bang. We were working with Elvis' engineer and music diviner, Cowboy Jack Clement. He reopened the studio so we could cut some tracks within the same four walls where Elvis recorded "Mystery Train." He found the old valve microphone the King had howled through; the reverb was the same reverb: "Train I ride, sixteen coaches long." It was a small tunnel of a place, but there was a certain clarity to the sound. You can hear it in those Sun records, and they are the ones for me -- leanness but not meanness. The King didn't know he was the King yet. It's haunted, hunted, spooky music. Elvis doesn't know where the train will take him, and that's why we want to be passengers. Jerry Schilling, the only one of the Memphis Mafia not to sell him out, told me a story about when he used to live at Graceland, down by the squash courts. He had a little room there, and he said that when Elvis was upset and feeling out of kilter, he would leave the big house and go down to his little gym, where there was a piano. With no one else around, his choice would always be gospel, losing and finding himself in the old spirituals. He was happiest when he was singing his way back to spiritual safety. But he didn't stay long enough. Self-loathing was waiting back up at the house, where Elvis was seen shooting at his TV screens, the Bible open beside him at St. Paul's great ode to love, Corinthians 13. Elvis clearly didn't believe God's grace was amazing enough.

Some commentators say it was the Army, others say it was Hollywood or Las Vegas that broke his spirit. The rock & roll world certainly didn't like to see their King doing what he was told. I think it was probably much more likely his marriage or his mother -- or a finer fracture from earlier on, like losing his twin brother, Jesse, at birth. Maybe it was just the big arse of fame sitting on him. I think the Vegas period is underrated. I find it the most emotional. By that point Elvis was clearly not in control of his own life, and there is this incredible pathos. The big opera voice of the later years -- that's the one that really hurts me. Why is it that we want our idols to die on a cross of their own making, and if they don't, we want our money back? But you know, Elvis ate America before America ate him. – Bono

The Beatles

I first heard of the Beatles when I was nine years old. I spent most of my holidays on Merseyside then, and a local girl gave me a bad publicity shot of them with their names scrawled on the back. This was 1962 or '63, before they came to America. The photo was badly lit, and they didn't quite have their look down; Ringo had his hair slightly swept back, as if he wasn't quite sold on the Beatles haircut yet. I didn't care about that; they were the band for me. The funny thing is that parents and all their friends from Liverpool were also curious and proud about this local group. Prior to that, the people in show business from the north of England had all been comedians. Come to think of it, the Beatles recorded for Parlophone, which was a comedy label. I was exactly the right age to be hit by them full on. My experience -- seizing on every picture, saving money for singles and EPs, catching them on a local news show -- was repeated over and over again around the world. It was the first time anything like this had happened on this scale. But it wasn't just about the numbers; Michael Jackson can sell records until the end of time, but he'll never matter to people as much as the Beatles did.

Every record was a shock when it came out. Compared to rabid R&B evangelists like the Rolling Stones, the Beatles arrived sounding like nothing else. They had already absorbed Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers and Chuck Berry, but they were also writing their own songs. They made writing your own material expected, rather than exceptional. John Lennon and Paul McCartney were exceptional songwriters; McCartney was, and is, a truly virtuoso musician; George Harrison wasn't the kind of guitar player who tore off wild, unpredictable solos, but you can sing the melodies of nearly all of his breaks. Most important, they always fit right into the arrangement. Ringo Starr played the drums with an incredibly unique feel that nobody can really copy, although many fine drummers have tried and failed. Most of all, John and Paul were fantastic singers. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison had stunningly high standards as writers. Imagine releasing a song like "Ask Me Why" or "Things We Said Today" as a B side. They made such fantastic records as "Paperback Writer" b/w "Rain" or "Penny Lane" b/w "Strawberry Fields Forever" and only put them out as singles. These records were events, and not just advance notice of an album release.

Then they started to really grow up. Simple love lyrics to adult stories like "Norwegian Wood," which spoke of the sour side of love, and on to bigger ideas than you would expect to find in catchy pop lyrics. They were pretty much the first group to mess with the aural perspective of their recordings and have it be more than just a gimmick. Brilliant engineers at Abbey Road Studios like Geoff Emerick invented techniques that we now take for granted in response to the group's imagination. Before the Beatles, you had guys in lab coats doing recording experiments in the Fifties, but you didn't have rockers deliberately putting things out of balance, like a quiet vocal in front of a loud track on "Strawberry Fields Forever." You can't exaggerate the license that this gave to everyone from Motown to Jimi Hendrix.

My absolute favorite albums are Rubber Soul and Revolver. On both records you can hear references to other music -- R&B, Dylan, psychedelia -- but it's not done in a way that is obvious or dates the records. When you picked up Revolver, you knew it was something different. Heck, they are wearing sunglasses indoors in the picture on the back of the cover and not even looking at the camera . . . and the music was so strange and yet so vivid. If I had to pick a favorite song from those albums, ift would be "And Your Bird Can Sing" . . . no, "Girl" . . . no, "For No One" . . . and so on, and so on. . . .

Their breakup album, Let It Be, contains songs both gorgeous and jagged. I suppose ambition and human frailty creep into every group, but they managed to deliver some incredible performances. I remember going to Leicester Square and seeing the film of Let It Be in 1970. I left with a melancholy feeling. The word Beatlesque has been in the dictionary for a while now. I can hear them in the Prince album Around the World in a Day; in Ron Sexsmith's tunes; in Harry Nilsson's melodies. You can hear that Kurt Cobain listened to the Beatles and mixed them in with punk and metal in some of his songs. You probably wouldn't be listening to the ambition of the latest OutKast record if the Beatles hadn't made the White Album into a double LP! I've co-written some songs with Paul McCartney and performed with him in concert on two occasions. In 1999, a little time after Linda McCartney's death, Paul did the Concert for Linda, organized by Chrissie Hynde. During the rehearsal, I was singing harmony on a Ricky Nelson song, and Paul called out the next tune: "All My Loving." I said, "Do you want me to take the harmony line the second time round?" And he said, "Yeah, give it a try." I'd only had thirty-five years to learn the part. It was a very poignant performance, witnessed only by the crew and other artists on the bill. At the show, it was very different. The second he sang the opening lines -- "Close your eyes, and I'll kiss you" -- the crowd's reaction was so intense that it all but drowned the song out. It was very thrilling but also rather disconcerting. Perhaps I understood in that moment one of the reasons why the Beatles had to stop performing. The songs weren't theirs anymore. They were everybody's. - Elvis Costello

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan and I started out from different sides of the tracks. When I first heard him, I was already in a band, playing rock & roll. I didn't know a lot of folk music. I wasn't up to speed on the difference he was making as a songwriter. I remember somebody playing "Oxford Town," from The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, for me. I thought, "There's something going on here." His voice seemed interesting to me. But it wasn't until we started playing together that I really understood it. He is a powerful singer and a great musical actor, with many characters in his voice. I could hear the politics in the early songs. It's very exciting to hear somebody singing so powerfully, with something to say. But what struck me was how the street had had such a profound effect on him: coming from Minnesota, setting out on the road and coming into New York. There was a hardness, a toughness, in the way he approached his songs and the characters in them. That was a rebellion, in a certain way, against the purity of folk music. He wasn't pussyfooting around on "Like a Rolling Stone" or "Ballad of a Thin Man." This was the rebel rebelling against the rebellion.

I learned early on with Bob that the people he hung around with were not musicians. They were poets, like Allen Ginsberg. When we were in Europe, there'd be poets coming out of the woodwork. His writing came directly out of a tremendous poetic influence, a license to write in images that weren't in the Tin Pan Alley tradition or typically rock & roll, either. I watched him sing "Desolation Row" and "Mr. Tambourine Man" in those acoustic sets in 1965 and '66. I had never seen anything like it -- how much he could deliver with a guitar and a harmonica, and how people would just take the ride, going through these stories and songs with him.

When he and I went to Nashville in 1966, to work on Blonde on Blonde, it was the first time I'd ever seen a songwriter writing songs on a typewriter. We'd go to the studio, and he'd be finishing up the lyrics to some of the songs we were going to do. I could hear this typewriter -- click, click, click, ring, really fast. He was typing these things out so fast; there was so much to be said. And he'd be changing things during a session. He'd have a new idea and try to incorporate that. That was something else he taught me early on. The Hawks were band musicians. We needed to know where the song was going to go, what the chord changes were, where the bridge was. Bob has never been big on rehearsing. He comes from a place where he just did the songs on acoustic guitar by himself. When we'd play the song with him, it would be, "How do we end it?" And he'd say, "Oh, when it's over, it's over. We'll just stop." We got so we were ready for anything -- and that was a good feeling. We'd think, "OK, this can take a left turn at any minute -- and I'm ready."

More than anything, in my own songwriting, the thing I learned from Bob is that it's OK to break those traditional rules of what songs are supposed to be: the length of a song, how imaginative you could get telling the story. It was great that someone had broken down the gates, opened up the sky to all of the possibilities. One thing that I don't think people realize is that to write the way he does, to get that many ideas into these very distinct melodies, you had to be really good at phrasing. His vocal phrasing was special. He got these characters and images across in a way that didn't feel stiff or forced, with a musical comfort so you could just take the ride and never question it. And a lot of times there was an attitude in his voice that worked for a particular record. I remember when he played Nashville Skyline for me. I was amazed at the character that he had pulled out of the bag for that.

I think Bob has a true passion for the challenge, for coming up with something in the music that makes him feel good, to keep on doing it and doing it, as he does now. The songs Bob is writing now are as good as any songs he's ever written. There's a wonderful honesty in them. He writes about what he sees and feels, about who he is. We spent a lot of time together in the 1970s. We were both living in Malibu and knew what was going on in our respective day-to-day lives. And I know Blood on the Tracks is a reflection of what was happening to him then. When he writes songs, he's telling me things about himself, holding up a mirror -- and I'm seeing it all clearly, like I've never seen it before.

From my knowledge of him, I don't think Bob ever wanted to be more than a good songwriter. When people are like, "Oh, my God, you're having an effect on culture and society" -- I doubt he thinks like that. I don't think Hank Williams understood why his songs were so much more moving than other people's songs. I think Bob is thinking, "I hope I can think of another really good song." He's putting one foot in front of the other and just following his bliss.

But Bob is a great barometer for young singers and songwriters. As soon as they think they've written something good -- "I'm pushing the envelope here, I've made a breakthrough" -- they should listen to one of his songs. He will always stand as the one to measure good work by. That's one of the greatest accomplishments of all. - Robbie Robertson

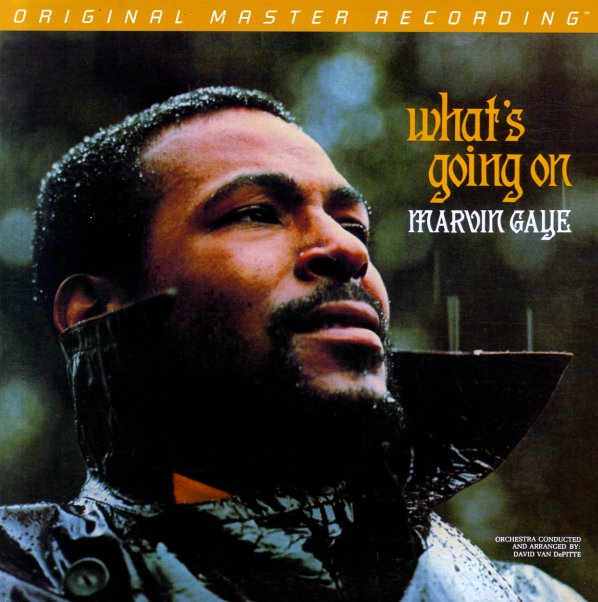

Marvin Gaye

At Motown, Marvin was one of the main characters in the greatest musical story ever told. Prior to that, nothing quite like Motown had ever existed -- all those songwriters, singers, producers working and growing together, part family, part business -- and I doubt seriously if it will ever happen like that again. And there's no question that Marvin will always be a huge part of the Motown legacy.

When Marvin first came to Motown, he was the drummer on all the early hits I had with the Miracles. He and I became close friends -- he was my brother, really -- and I did a lot of production and wrote a lot of songs for him: "Ain't That Peculiar," "I'll Be Doggone." Of course, that means that I spent a lot of time waiting for Marvin. See, Marvin was basically late coming to the studio all the time. But I never minded, because I knew that whenever Marvin did get there, he was going to sing my song in a way that I had never imagined it. He would Marvinize my songs, and I loved it. Marvin could sing anything, from gospel to gutbucket blues, to jazz, to pop.

But Marvin was much more than just a great singer. He was a great record maker, a gifted songwriter, a deep thinker -- a real artist in the true sense. What's Going On is the most profound musical statement in my lifetime. It never gets dated. Listen to it right now -- "Brother, brother, brother/ There's far too many of you dying" -- it's even more poignant than it was when he made it. I still remember when I would go by Marvin's house and he was working on it, he would say, "Smoke, this album is being written by God, and I'm just the instrument that he's writing it through."

Marvin really had it all -- that voice, that soul, that look, too. He was one very handsome man, and he had sex appeal that women were drawn to always. And his music was sexy, not just "Let's Get It On" or "I Want You," but all of it. You couldn't blame women for falling in love with Marvin. Beyond being his friend and his brother, I'm a major Marvin Gaye fan. At the time Marvin was alive, his was my favorite male voice. I said before that when you worked with Marvin, it meant you were waiting for Marvin. But Marvin was always worth the wait. I suppose that in a way, I'm still waiting for Marvin. – Smokey Robinson

U2

I don't buy weekend tickets to Ireland and hang out in front of their gates, but U2 are the only band whose entire catalog I know by heart. The first song on The Unforgettable Fire, "A Sort of Homecoming," I know backward and forward -- it's so rousing, brilliant and beautiful. It's one of the first songs I played to my unborn baby. The first U2 album I ever heard was Achtung Baby. It was 1991, and I was fourteen years old. Before that, I didn't even know what albums were. From that point, I worked backward -- every six months, I'd get to buy a new U2 album. The sound they pioneered -- the driving bass and drums underneath and those ethereal, effects-laden guitar tracks floating out from above -- was nothing that had been heard before. They may be the only good anthemic rock band ever. Certainly they're the best.

What I love most about U2 is that the band is more important than any of their songs or albums. I love that they're best mates and have an integral role in one another's lives as friends. I love the way that they're not interchangeable -- if Larry Mullen Jr. wants to go scuba diving for a week, the rest of the band can't do a thing. U2 -- like Coldplay -- maintain that all songs that appear on their albums are credited to the band. And they are the only band that's been around for twenty years with no member changes and no big splits.

It's amazing that the biggest band in the world has so much integrity and passion in their music. Our society is thoroughly screwed, fame is a ridiculous waste of time, and celebrity culture is disgusting. There are only a few people around brave enough to talk out against it, who use their fame in a good way. And every time I try, I feel like an idiot, because I see Bono actually getting things achieved. While everyone else is swearing at George Bush, Bono is the one who rubs Bush's back and gets a billion dollars for Africa. People can be so cynical -- they don't like do-gooders -- but Bono's attitude is, "I don't care what anybody thinks, I'm going to speak out." He's accomplished so much with Greenpeace, in Sarajevo, at the concert to shut down the Sellafield nuclear plant, and he still runs the gantlet. When the time came for Coldplay to think about fair trade, we took his lead to speak out regardless of what anyone may think. That's what we've learned from U2: You have to be brave enough to be yourself. – Chris Martin

Bruce Springsteen

In many ways, Bruce Springsteen is the embodiment of rock & roll. Combining strains of Appalachian music, rockabilly, blues and R&B, his work epitomizes rock's deepest values: desire, the need for freedom and the search to find yourself. All through his songs there is a generosity and a willingness to portray even the simplest aspects of our lives in a dramatic and committed way.

The first time I heard him play was at a small club, the Bitter End in New York, where he did a guest set. He had this descriptive power -- it was just an amazing display of lyrical prowess. I asked him where he was from, and he sort of grinned and said he was from New Jersey. In those days people used to joke about New Jersey. There was this collective complex that people from New Jersey had about what it meant to be from there, and he just smiled because he knew where he was from.

The next time I saw him play it was with his band, the one with David Sancious in it. I'd never seen anybody do what he was doing: He would play acoustic guitar and dance all over the place, and the guitar wasn't plugged into anything. There wasn't this meticulous need to have every note heard. It was so powerful, and it filled that college gym with so much emotion that it didn't matter if you couldn't hear every note. It was drama, his approach to music, something that he would expand on many times over, but it was there from the beginning.

A year or so later I saw him play in L.A., with Max Weinberg, Clarence Clemons and Steve Van Zandt in the band, and it was even more dramatic -- the use of lights and the way it was staged. There were these events built into the music. I went to see them the second night, and I guess I expected it to be the same thing, but it was completely different. It was obvious that they were drawing on a vocabulary. It was exhilarating, and at the bottom of it all there was all this joy and fun and a sense of brotherhood, of being outsiders who had tremendous power and a story to tell.

Bruce has been unafraid to take on the tasks associated with growing up. He's a family man, with kids and the same values and concerns as working-class Americans. It runs all through his work, the idea of finding that one person and making a life together. Look at "Rosalita": Her mother doesn't like him, her father doesn't like him, but he's come for her. Or in "The River," where he gets Mary pregnant and for his nineteenth birthday he gets a union card and a wedding coat. That night they go to the river and dive in. For those of us who are ambivalent about marriage, the struggle for love in a world of impermanence is summed up by the two of them diving into that river at night. Bruce's songs are filled with these images, but they aren't exclusively the images of working-class people. It just happens to be where he's from.

Bruce has all kinds of influences, from Chuck Berry and Gary "U.S." Bonds to Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie. But he's also a lot like Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and James Dean -- people whose most indistinct utterances have been magnified to communicate volumes. Bruce has always had enormous range in terms of subject and emotion, as well as volume -- his quietest stuff is as quiet as you will ever hear anyone sing, but at his loudest he is, well, he's the loudest. But he's always worked on a very large scale, a scale that is nothing short of heroic. He is one of the few songwriters who works on a scale that is capable of handling the subject of our national grief and the need to find a response to September 11th. His sense of music as a healing power, of band-as-church, has always been there, woven into the fabric of his songs. He's got his feet planted on either side of that great divide between black and white gospel, between blues and country, between rebellion and redemption. – Jackson Browne

Neil Young

There's a rare contradiction in Neil Young's work. He works so hard as a songwriter, and he's written a phenomenal number of perfect songs. And, at the same time, he doesn't give a fuck. That comes from caring about essence. There can be things out of tune and all wild-sounding and not recorded meticulously. And he doesn't care. He's made whole albums that aren't great, and instead of going back to a formula that he knows works, he would rather represent where he is at the time. That's what's so awesome: watching his career wax and wane according to the truth of his character at the moment. It's never phony. It's always real. The truth is not always perfect.

I can't say enough about how much I love Crazy Horse. The sound is so deep, the groove is so deep -- even when they're off, it still sounds great, because they feel it so much. I don't usually go for that approach. I like Sly and the Family Stone, Miles Davis and Mingus. I like consummate steady musicianship. I grew up on jazz. I didn't listen to rock music until I played in my first rock band when I was in high school. I went from progressive to Hendrix to funk to full-on L.A. punk. That's when I had the realization that emotion and content, no matter how simple, were valuable. A great one-chord punk song became as important to me as a Coltrane solo, and I've had the same feeling about Neil Young. He changed the way I thought about rock music. As a bass player, I used to be into very boisterous, syncopated and rhythmically complex songs. After hearing Neil, I appreciated simplicity, the poignancy of "less is more."

My favorite Neil album is Zuma, with "Pardon My Heart" and "Lookin' for a Love": "But I hope I treat her kind/And don't mess with her mind/When she starts to see the darker side of me." And "Tell Me Why," on After the Gold Rush -- when he says, "Is it hard to make arrangements with yourself/When you're old enough to repay but young enough to sell?" it feels like me. I know I'm not alone. Tonight's the Night is probably the greatest raw rock record ever made, on a level with the Stooges' Fun House or any Hendrix album. It's such a mess, with stuff recorded so loud that it distorts. The background vocals are completely out of tune. And I wouldn't change a note. It's the spirit of what rock music is, and it's the reason to play rock music.

Neil is the guy I look at when I think about getting older in a rock band and still having dignity and relevance and honesty. He's never, ever sold out, and he's never pretended to be anything other than what he is. The Chili Peppers get offers all the time to sell songs for commercials and tour sponsorships, and our manager says it's not considered selling out anymore. It's the smart move, he says. Maybe we could whore ourselves out for the right price someday. I don't know. But I always think, "Would Neil Young do this?" And the answer is no. Neil Young wouldn't fuckin' do it. – Flea

The Band

I've used The Band as an example for my career. When I first tried to get record deals, nobody knew how to market me, because my sound didn't necessarily fit into any stereotypes. But the Band did a little bit of everything. I remember when Music From Big Pink came out, in 1968. I was living in Arkansas at the time. You couldn't categorize the Band's sound, but it was so organic -- a little bit country, a little bit roots, a little bit mountain, a little bit rock -- and their vocal styles and harmonies totally set them apart. Each band member brought something, because they were all consummate musicians.

Their work as the Hawks on Dylan's 1966 tour is some of the best rock & roll ever made, with Robbie Robertson playing just amazing guitar. The Band let Dylan branch out stylistically. In his writing, Dylan was getting away from those heavy, metaphorical songs on Blonde on Blonde and writing cool little tunes.

Their songs are uncoverable -- who can pull off Richard Manuel's incredible high voice? -- but we tried. Any time we sat around singing songs, someone would inevitably pull out a version of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" and drunken and stoned singalongs of "The Weight." My favorite song was "It Makes No Difference," from Northern Lights-Southern Cross. The sentiment of it is so heart-wrenching, and the performance is so honest. This guy is saying that his lover has just left him, and he's totally devastated. It's one of the most beautiful melodies I've ever heard.

There is an element of sadness about the Band. The Last Waltz, despite its wonderful music, was sad to see because they had so much more to give. Richard Manuel's death was really tragic. I got to meet Garth Hudson -- he played on a demo I did back in the mid-Eighties. I just remember he was really quiet, soft-spoken and real sweet. And he played like an angel. – Lucinda Williams

The Who

The Who began as spectacle. They became spectac-ular. Early on, the band was in pure demolition mode; later, on albums like Tommy and Quadrophenia, they coupled that raw energy with precision and desire to complete musical experiments on a grand scale. They asked, "What were the limits of rock & roll? Could the power of music actually change the way you feel?" Pete Townshend allowed that there be spiritual value in music. They were an incredible band whose main songwriter happened to be on a quest for reason and harmony in his life. He shared that journey with the listener, becoming an inspiration for others to seek out their own path - this while being in the Guinness book of world records as the world's loudest band.

Presumptuously I speak for all Who fans when I say being a fan of the Who has incalculably enriched my life. What disturbs me about the Who is the way they smashed through every door of rock & roll, leaving rubble and not much else for the rest of us to lay claim to. In the beginning they took on an arrogance when, as Pete says, "We were actually a very ordinary group." As they became accomplished, this attitude stuck. Therein lies the thread to future punks. They wanted to be louder, so they had Jim Marshall invent the 100-watt amp. Needed more volume, so they began stacking them. It is said that the first guitar feedback ever to make it to record was on "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere," in 1965. The Who told stories within the confines of a song and, over the course of an entire album, pushed boundaries. How big of a story could be told? And how would it transmit (pre-video screens, etc.) to a large crowd? Smash the instruments? Keith Moon said they wanted to grab the audience by the balls. Pete countered that like the German autodestruct movement, where they made sculpture that would collapse and buildings that would explode, it was high art.

I was around nine when a baby sitter snuck Who's Next onto the turntable. The parents were gone. The windows shook. The shelves were rattling. Rock & roll. That began an exploration into music that had soul, rebellion, aggression, affection. Destruction. And this was all Who music. There was the mid-Sixties maximum-R&B period: mini-operas, Woodstock, solo records. Imagine, as a kid, stumbling upon the locomotive that is Live at Leeds. "Hi, my name is Eddie. I'm ten years old and I'm getting my fucking mind blown!" The Who on record were dynamic. Roger Daltrey's delivery allowed vulnerability without weakness; doubt and confusion, but no plea for sympathy. (You should hear Roger's vocal on a song called "Lubie [Come Back Home]," a bonus track from the My Generation reissue. It's top-gear.)

The Who quite possibly remain the greatest live band ever. Even the list-driven punk legend and music historian Johnny Ramone agrees with me on this. You can't explain Keith Moon or his playing. John Entwistle was an enigma unto himself, another virtuoso musical oddity. Roger turned his mike into a weapon, seemingly in self-defense. All the while, Pete was leaping into the rafters wielding a Seventies Gibson Les Paul, which happens to be a stunningly heavy guitar. As a live group, they created momentum, and they seemed to be released by the ritual of their playing. (Check out "A Quick One," from The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus.)

In Chicago recently, I saw Pete wring notes out of his guitar like a mechanic squeezing oil from a rag. I watched as the guitar became a living being, one getting its body bashed and its neck strangled. As Pete set it down, I swear I sensed relief coming from that guitar. A Stratocaster with sweat on it. The guitar's sweat.

John and Keith made the Who what they were. Now they're different, but still the Who. Roger's a rock. And at this point Pete has been through and survived more than anyone in rock royalty. Perhaps even beyond Keith Richards, who was actually guilty of most things he was accused of. Drummer Zak Starkey played me a new song a while back, "Real Good Looking Boy." It was beyond moving.

The songwriter-listener relationship grows deeper after all the years. Pete saw that "a celebrity in rock is charged by the audience with a function, like, 'You stand there and we will know ourselves.' Not 'You stand there and we will pay you loads of money to keep us entertained as we eat our oysters.' " He saw the connection could be profound. He also realized the audience may say, "When we're finished with you, we'll replace you with somebody else." For myself and so many others (including shopkeepers, foremen, professionals, bellboys, gravediggers, directors, musicians), they won't be replaced. Yes, Pete, music can change you. – Eddie Vedder

Dr. Dre

Do hip-hop producers hold Dr. Dre in high esteem? It's like asking a Christian if he believes Christ died for his sins. Dre has a whole coast on his back. He discovered Snoop -- one of the two greatest living rappers, along with Jay-Z -- and signed Eminem, 50 Cent and now the Game. He takes artists with great potential and makes them even better. I wonder where I'd be right now if Dre had discovered me.

I remember hearing Dre's music before I really knew who he was. I had a tape of Eazy-E's Eazy-Duz-It when I was ten years old (until my mother found out it had curses on it and confiscated it). I didn't know what "production" was back then, but I knew I loved the music. The more I learned about producing hip-hop, the more I respected what Dre was doing. Think about how on old N.W. A records the beat would change four or five times in a single song. A million people can program beats, but can they put together an entire album like it's a movie? When I was learning to produce, working in a home studio in my mother's crib, I tried to make beats that sounded exactly like Timbaland's, DJ Premier's, Pete Rock's and, especially, Dr. Dre's. Dre productions like Tupac's "California Love" were just so far beyond what I was doing that I couldn't even comprehend what was going on. I had no idea how to get to that point, how to layer all those instruments. The Chronic is still the hip-hop equivalent to Stevie Wonder's Songs in the Key of Life. It's the benchmark you measure your album against if you're serious. But it's "Xxplosive," off 2001, that I got my entire sound from -- if you listen to the track, it's got a soul beat, but it's done with those heavy Dre drums. Listen to "This Can't Be Life," a track I did for Jay-Z's Dynasty album, and then listen to "Xxplosive." It's a direct bite. I just met Dre for the first time in December -- he asked me to produce a track ("Dreams") for the Game's record. At first I was starstruck, but within thirty minutes I was begging him to mix my next album. He's the definition of a true talent: Dre feels like God placed him here to make music, and no matter what forces are aligned against him, he always ends up on the mountaintop. - Kanye West

The Clash

The Clash, more than any other group, kick-started a thousand garage bands across Ireland and the U.K. For U2 and other people of our generation, seeing them perform was a life-changing experience. There's really no other way to describe it.

I can vividly remember when I first saw the Clash. It was in Dublin in October 1977. They were touring behind their first album, and they played a 1,200-capacity venue at Trinity College. Dublin had never seen anything like it. It really had a massive impact around here, and I still meet people who are in the music business today -- maybe they are DJs, maybe they are in bands -- because they saw that show.

U2 were a young band at the time, and it was a complete throw-down to us. It was like: Why are you in music? What the hell is music all about, anyway? The members of the Clash were not world-class musicians by any means, but the racket they made was undeniable -- the pure, visceral energy and the anger and the commitment. They were raw in every sense, and they were not ashamed that they were about much more than playing with precision and making sure the guitars were in tune. This wasn't just entertainment. It was a life-and-death thing. They made it possible for us to take our band seriously. I don't think that we would have gone on to become the band we are if it wasn't for that concert and that band. There it was. They showed us what you needed. And it was all about heart.

The social and political content of the songs was a huge inspiration, certainly for U2. It was the call to wake up, get wise, get angry, get political and get noisy about it. It's interesting that the members were quite different characters. Paul Simonon had an art-school background, and Joe Strummer was the son of a diplomat. But you really sensed they were comrades in arms. They were completely in accord, railing against injustice, railing against a system they were just sick of. And they thought it had to go.

I saw them a couple of times after the Dublin show, and they always had something fresh going on. It's a shame that they weren't around longer. The music they made is timeless. It's got so much fighting spirit, so much heart, that it just doesn't age. You can still hear it in Green Day and No Doubt, Nirvana and the Pixies, certainly U2 and Audioslave. There wasn't a minute when you sensed that they were coasting. They meant it, and you can hear it in their work. – The Edge

SONGS OF THE DAY

Trapeze Swinger - Iron & Wine

Please, remember me, Happily, By the rosebush laughing

With bruises on my chin, The time when We counted every black car passing

Your house beneath the hill, And up until, Someone caught us in the kitchen

With maps, a mountain range, A piggy bank, A vision too removed to mention

But

Please, remember me, Fondly, I heard from someone you're still pretty

And then, They went on to say, That the pearly gates

Had some eloquent graffiti: Like 'We'll meet again', And 'Fuck the man'

And 'Tell my mother not to worry'

And angels with their gray Handshakes Were always done in such a hurry

And

Please, remember me, At Halloween, Making fools of all the neighbors

Our faces painted white, By midnight, We'd forgotten one another

And when the morning came, I was ashamed, Only now it seems so silly

That season left the world And then returned And now you're lit up by the city

So

Please, remember me, Mistakenly, In the window of the tallest tower call

Then pass us by, But much too high, To see the empty road at happy hour

Leave and resonate, Just like the gates, Around the holy kingdom

With words like 'Lost and Found' and 'Don't Look Down' and 'Someone Save Temptation'

And

Please, remember me, As in the dream, We had as rug-burned babies

Among the fallen trees, And fast asleep, Aside the lions and the ladies

That called you what you like, And even might Give a gift for your behavior

A fleeting chance to see A trapeze Swing as high as any savior

But

Please, remember me, My misery, And how it lost me all I wanted

Those dogs that love the rain, And chasing trains, The colored birds above there running

In circles round the well, And where it spells, On the wall behind St. Peter's

So bright with cinder gray And spray paint 'Who the hell can see forever?'

And

Please, remember me, Seldomly, In the car behind the carnival

My hand between your knees You turn from me

And said 'The trapeze act was wonderful but never meant to last'

The clown that passed Saw me just come up with anger

When it filled with circus dogs The parking lot Had an element of danger

So

Please, remember me, Finally, And all my uphill clawing My dear

But if i make The pearly gates Do my best to make a drawing

Of God and Lucifer A boy and girl An angel kissing a sinner

A monkey and a man; a marching band

All around the frightened trapeze swingers

Human Nature - Michael Jackson

Looking out, Across the night-time, The city winks a sleepless eye

Hear her voice, Shake my window, Sweet seducing sighs

Get me out, Into the night-time, Four walls won’t hold me tonight

If this town, Is just an apple, Then let me take a bite

If they say - Why, why, tell ’em that is human nature

Why, why, does he do me that way?

If they say - Why, why, tell ’em that is human nature

Why, why, does he do me that way?

Reaching out, To touch a stranger, Electric eyes are ev’rywhere

See that girl, She knows I’m watching, She likes the way I stare

If they say - Why, why, tell ’em that is human nature

Why, why, does he do me that way?

If they say - Why, why, tell ’em that is human nature

Why, why, does he do me that way?

I like livin’ this way

I like lovin’ this way

Looking out Across the morning, The city’s heart begins to beat

Reaching out I touch her shoulder, I’m dreaming of the street

If they say - Why, why, tell ’em that is human nature

Why, why, does he do me that way?

I like livin’ this way

OTHER

1. Why didn’t they embalm the Pope?

Pilgrims traveled to Rome this week to view the body of Pope John Paul II, who died last Saturday. Vatican officials say the body has not been embalmed but only "prepared" for viewing. How long will it take for the pope to decompose? And why wasn't he embalmed in the first place? Barring unusual conditions, putrefaction usually sets in within about a week. At that stage of decomposition, bacteria from the intestines start breaking down body tissues and releasing foul-smelling gases and fluids. Pressure within the body causes abdominal bloating and the "purge" of fluids through the nose and mouth.

The speed at which a body decomposes depends on a number of factors, including temperature and body type. As a general rule, the bodies of fat people in a hot and humid environment will rot more quickly than those of skinny people in cooler weather. The temperature in Rome this week has been in the low 60s, but it's likely colder within the stone walls of St. Peter's. On the other hand, the thousands of people filing through the Basilica have probably generated a fair bit of heat. Decomposition could be staved off by refrigeration, but the pope's body appears to be lying on an uncovered catafalque.

There has been intense speculation about the state of the pope's body among American death industry professionals. Some claim to have identified a purpling of the lips in photographs, suggestive of decay produced by bacterial populations in the mouth and on the gums. Others say the pope shows signs of bloating. There seems to be no strict Vatican policy on how the pope's body should be preserved. Most recent popes have been embalmed, including the last four before John Paul II: Pius XII, John XXIII, Paul VI, and John Paul I. While he didn't say anything specific about embalming in his testament, John Paul II did state that he wanted to be buried "in the bare earth, not a tomb."

The unembalmed body of John Paul II may have been partially preserved without being subjected to the whole process. A full-scale embalming (which is most common in the United States, New Zealand, and Australia) takes several steps. The embalmer first disinfects the outside of the body, then inserts tubes into a major artery and a major vein. Next, he pumps a mixture of fixatives, dyes, and perfume into the artery using an "embalming machine" and flushes blood and other fluids out through the open vein. Finally, he sucks gases and liquids out of the abdominal and chest cavities through a long tube and replaces them with more fixative. The pope's body did not go through all these steps, but it's possible that his corpse was treated only in the cavities or partially fixed with surface injections.

John Paul II will not be the first pope to decompose in public. In August of 1978, the body of Paul VI "took on a greenish tinge," and fans were installed in the Basilica to disperse the smell. Twenty years earlier, a maverick doctor persuaded the Vatican to let him try an experimental embalming technique on the body of Pope Pius XII, with disastrous consequences—the body turned black and disintegrated in the casket. Pope John XXIII, who died in 1963, seems to have been treated better: When his embalmed body was disinterred in 2001, it looked to be in pretty good shape. If John Paul II is eventually canonized, he might not have to worry. Some Catholics believe that the bodies of saints are "incorruptible." That is, they never decompose.

2. The Shins play Toronto April 17th at Kool Haus.

3. The one bedroom semi-detached house next to the one we’re renting, 131 Alcorn Avenue, is on sale for $600,000.

4. Fever Pitch (NYTimes) – To watch "Fever Pitch," the new, thoroughly winning if not especially good film by Peter and Bobby Farrelly, is to appreciate, yet again, that the great loves of our lives are rarely perfect. That is, of course, not big news. If Hollywood has taught us anything over the last century it is that every so often a seemingly ordinary commercial enterprise can afford us fleeting access to the sublime. And for my money, there are few movie moments right now more sublime than the image of Drew Barrymore running across a major league baseball field and, with that famous jaw jutting into the wind, dodging ballplayers and storybook clichés to save the windup of this imperfectly true romance.

Written by the industrial-strength team of Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel ("Splash," "City Slickers") and loosely based on the Nick Hornby memoir of the same title, "Fever Pitch" is one of the few Farrelly movies that the brothers didn't also (officially) write. And while it features a lengthy sequence involving regurgitation - mind you, an unabashedly romantic sequence involving regurgitation - this is the first of their films that doesn't lean on sight gags and the various insults and humiliations that come with having an all-too-human body. When Ms. Barrymore's character, Lindsey Meeks, turns an alarming shade of green after a bout of food poisoning, the Farrellys sneak in some delightful business with a dog and an electric toothbrush, but otherwise keep an uncharacteristically discreet distance.

For longtime Farrelly fans, this turn to relative discretion may set off alarms. Ever since their first movie, the gleefully stupid "Dumb and Dumber," the brothers have been doing their part to flush American comedy down the toilet. In contrast to many of their barf-bag brethren, however, who seem stuck in the anal and oral stages, content to manufacture poop jokes and sail along on their own flatulence, the Farrellys have consistently pushed their comedy into new territory, including fatherhood, brotherly love and romance. Equal parts Three Stooges and classic screwball comedy, "There's Something About Mary" was a crudely funny valentine of a movie, but a valentine nonetheless. In their last comedy, "Stuck on You," a story about conjoined twins with conflicting desires, the brothers sent another valentine, this time to each other.

"Stuck on You" didn't fully work and neither does "Fever Pitch," but it's good to see the Farrellys pushing their own comedy comfort level, if only because they're running out of body fluids to exploit. Ms. Barrymore's character is an alpha-gal Bostonian with designer tastes, a high-stakes consultant who crunches numbers for high-end clients. One day at work, she finds herself performing career show-and-tell for some elementary school math nerds and their equally nerdy teacher, Ben Wrightman (Jimmy Fallon). After some hemming and hawing, he asks her out and she hesitantly agrees. It isn't that he isn't cute (with his fluttery lashes and tentative smile, Mr. Fallon has cute down). The problem, one of her friends suggests, may be that she makes more money. After all, when it comes to most men, "It's like you're dating yourself."

But Ben isn't like most men and it's the very specific way in which he stands apart from the herd that's meant to give "Fever Pitch" its singular kick. What makes Ben special isn't his love for teaching, the way he never tucks in his shirt or any of the little things that make up the sum of a person; it's that he is a major league Red Sox fan, an obsessive, a true believer, a nut. Having been inducted into the Sox cult at the impressionable age of 8, Jimmy has turned the team into his church and his home. A reproduction of the Green Monster - the left field wall in Fenway Park - covers half his living room. He sleeps in a Sox T-shirt, buys beer with a Sox credit card. He even uses Yankees toilet paper. For Lindsey, who first falls for the man she calls Winter Guy only to end up a few months later with the single-minded demon she comes to know as Summer Guy, the road to happiness (or maybe madness) may be lined with team jerseys, Johnny Damon bobble-head dolls and countless iterations of red-and-white socks. Working off of Mr. Hornby's memoir, which recounts his lifelong obsession with a soccer team, the filmmakers try to attenuate Ben's fixation and balance the lopsided relationship by turning Lindsey into a workaholic. But her friendships have nothing to do with work and her apartment doesn't resemble a 12-year-old's rumpus room. Other than the fact that she looks like Drew Barrymore and is impossibly beautiful, Lindsey is just like any other overworked single woman who has ever turned a blind eye to a beer gut, a receding hair line and years of indulgent mothering for a date.

Try as they might, the Farrellys don't seem wholly comfortable with this material. Unlike Chris and Paul Weitz, who translated Mr. Hornby's novel "About a Boy" to the screen with such fluidity, the Farrellys have a hard time finding the right rhythm for their film, perhaps because for once the actors aren't spinning in circles. This is the first Farrelly movie not stuffed to the gills with comic bells and whistles and booming yuks, which may explain why the first 20 minutes are so excruciating. The film has the flat lighting and sound of canned television, and the actors look as if they have been dropped on the set without instruction. Things improve as the story unfolds, or maybe I was just too eager to see it all work out to continue fussing about the filmmaking. Still, despite the visual clumsiness and the production's tattered seams, I found myself rooting for this movie anyway, partly because Lindsey and Ben make a nice fit, as do the actors playing them, partly because the Farrellys bring so much heart to their movies, and partly because Ms. Barrymore inspires more goodwill than any other young actress I can think of working today in American movies. She doesn't give a performance for the ages in "Fever Pitch" (we may have to wait for her movie with Curtis Hanson, "Lucky You," to see what she is capable of), but she does enough. Like a loyal Sox fan, you root hard for her to make it across that baseball field, just as you root hard for the Farrellys, hoping against hope that they have hit another one out of the park.

4. Currently reading: Alice Munro’s Runaway and Andrea Levy’s Small Island.

from Rolling Stone

Elvis Presley

Out of Tupelo, Mississippi, out of Memphis, Tennessee, came this green, sharkskin-suited girl chaser, wearing eye shadow -- a trucker-dandy white boy who must have risked his hide to act so black and dress so gay. This wasn't New York or even New Orleans; this was Memphis in the Fifties. This was punk rock. This was revolt. Elvis changed everything -- musically, sexually, politically. In Elvis, you had the whole lot; it's all there in that elastic voice and body. As he changed shape, so did the world: He was a Fifties-style icon who was what the Sixties were capable of, and then suddenly not. In the Seventies, he turned celebrity into a blood sport, but interestingly, the more he fell to Earth, the more godlike he became to his fans. His last performances showcase a voice even bigger than his gut, where you cry real tears as the music messiah sings his tired heart out, turning casino into temple. In Elvis, you have the blueprint for rock & roll: The highness -- the gospel highs. The mud -- the Delta mud, the blues. Sexual liberation. Controversy. Changing the way people feel about the world. It's all there with Elvis.

I was barely conscious when I saw the '68 comeback special, at eight years old -- which was probably an advantage. I hadn't the critical faculties to divide the different Elvises into different categories or sort through the contradictions. Pretty much everything I want from guitar, bass and drums was present: a performer annoyed by the distance from his audience; a persona that made a prism of fame's wide-angle lens; a sexuality matched only by a thirst for God's instruction. But it's that elastic spastic dance that is the most difficult to explain -- hips that swivel from Europe to Africa, which is the whole point of America, I guess. For an Irish boy, the voice might have explained the sexiness of the U.S.A., but the dance explained the energy of this new world about to boil over and scald the rest of us with new ideas on race, religion, fashion, love and peace. These were ideas bigger than the man who would break the ice for them, ideas that would later confound the man who took the Anglo-Saxon stiff upper lip and curled it forever. He was "Elvis the Pelvis," with one hand on the blues terminal and the other on the gospel, which is the essence of rock & roll, a lightning flash running along his spine, electroshock therapy for a generation about to refuse numbness, both male and female, black and white.

I recently met with Coretta Scott King, John Lewis and some of the other leaders of the American civil-rights movement, and they reminded me of the cultural apartheid rock & roll was up against. I think the hill they climbed would have been much steeper were it not for the racial inroads black music was making on white pop culture. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival were all introduced to the blues through Elvis. He was already doing what the civil-rights movement was demanding: breaking down barriers. You don't think of Elvis as political, but that is politics: changing the way people see the world.

In the Eighties, U2 went to Memphis, to Sun Studio -- the scene of rock & roll's big bang. We were working with Elvis' engineer and music diviner, Cowboy Jack Clement. He reopened the studio so we could cut some tracks within the same four walls where Elvis recorded "Mystery Train." He found the old valve microphone the King had howled through; the reverb was the same reverb: "Train I ride, sixteen coaches long." It was a small tunnel of a place, but there was a certain clarity to the sound. You can hear it in those Sun records, and they are the ones for me -- leanness but not meanness. The King didn't know he was the King yet. It's haunted, hunted, spooky music. Elvis doesn't know where the train will take him, and that's why we want to be passengers. Jerry Schilling, the only one of the Memphis Mafia not to sell him out, told me a story about when he used to live at Graceland, down by the squash courts. He had a little room there, and he said that when Elvis was upset and feeling out of kilter, he would leave the big house and go down to his little gym, where there was a piano. With no one else around, his choice would always be gospel, losing and finding himself in the old spirituals. He was happiest when he was singing his way back to spiritual safety. But he didn't stay long enough. Self-loathing was waiting back up at the house, where Elvis was seen shooting at his TV screens, the Bible open beside him at St. Paul's great ode to love, Corinthians 13. Elvis clearly didn't believe God's grace was amazing enough.

Some commentators say it was the Army, others say it was Hollywood or Las Vegas that broke his spirit. The rock & roll world certainly didn't like to see their King doing what he was told. I think it was probably much more likely his marriage or his mother -- or a finer fracture from earlier on, like losing his twin brother, Jesse, at birth. Maybe it was just the big arse of fame sitting on him. I think the Vegas period is underrated. I find it the most emotional. By that point Elvis was clearly not in control of his own life, and there is this incredible pathos. The big opera voice of the later years -- that's the one that really hurts me. Why is it that we want our idols to die on a cross of their own making, and if they don't, we want our money back? But you know, Elvis ate America before America ate him. – Bono

The Beatles

I first heard of the Beatles when I was nine years old. I spent most of my holidays on Merseyside then, and a local girl gave me a bad publicity shot of them with their names scrawled on the back. This was 1962 or '63, before they came to America. The photo was badly lit, and they didn't quite have their look down; Ringo had his hair slightly swept back, as if he wasn't quite sold on the Beatles haircut yet. I didn't care about that; they were the band for me. The funny thing is that parents and all their friends from Liverpool were also curious and proud about this local group. Prior to that, the people in show business from the north of England had all been comedians. Come to think of it, the Beatles recorded for Parlophone, which was a comedy label. I was exactly the right age to be hit by them full on. My experience -- seizing on every picture, saving money for singles and EPs, catching them on a local news show -- was repeated over and over again around the world. It was the first time anything like this had happened on this scale. But it wasn't just about the numbers; Michael Jackson can sell records until the end of time, but he'll never matter to people as much as the Beatles did.

Every record was a shock when it came out. Compared to rabid R&B evangelists like the Rolling Stones, the Beatles arrived sounding like nothing else. They had already absorbed Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers and Chuck Berry, but they were also writing their own songs. They made writing your own material expected, rather than exceptional. John Lennon and Paul McCartney were exceptional songwriters; McCartney was, and is, a truly virtuoso musician; George Harrison wasn't the kind of guitar player who tore off wild, unpredictable solos, but you can sing the melodies of nearly all of his breaks. Most important, they always fit right into the arrangement. Ringo Starr played the drums with an incredibly unique feel that nobody can really copy, although many fine drummers have tried and failed. Most of all, John and Paul were fantastic singers. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison had stunningly high standards as writers. Imagine releasing a song like "Ask Me Why" or "Things We Said Today" as a B side. They made such fantastic records as "Paperback Writer" b/w "Rain" or "Penny Lane" b/w "Strawberry Fields Forever" and only put them out as singles. These records were events, and not just advance notice of an album release.

Then they started to really grow up. Simple love lyrics to adult stories like "Norwegian Wood," which spoke of the sour side of love, and on to bigger ideas than you would expect to find in catchy pop lyrics. They were pretty much the first group to mess with the aural perspective of their recordings and have it be more than just a gimmick. Brilliant engineers at Abbey Road Studios like Geoff Emerick invented techniques that we now take for granted in response to the group's imagination. Before the Beatles, you had guys in lab coats doing recording experiments in the Fifties, but you didn't have rockers deliberately putting things out of balance, like a quiet vocal in front of a loud track on "Strawberry Fields Forever." You can't exaggerate the license that this gave to everyone from Motown to Jimi Hendrix.

My absolute favorite albums are Rubber Soul and Revolver. On both records you can hear references to other music -- R&B, Dylan, psychedelia -- but it's not done in a way that is obvious or dates the records. When you picked up Revolver, you knew it was something different. Heck, they are wearing sunglasses indoors in the picture on the back of the cover and not even looking at the camera . . . and the music was so strange and yet so vivid. If I had to pick a favorite song from those albums, ift would be "And Your Bird Can Sing" . . . no, "Girl" . . . no, "For No One" . . . and so on, and so on. . . .

Their breakup album, Let It Be, contains songs both gorgeous and jagged. I suppose ambition and human frailty creep into every group, but they managed to deliver some incredible performances. I remember going to Leicester Square and seeing the film of Let It Be in 1970. I left with a melancholy feeling. The word Beatlesque has been in the dictionary for a while now. I can hear them in the Prince album Around the World in a Day; in Ron Sexsmith's tunes; in Harry Nilsson's melodies. You can hear that Kurt Cobain listened to the Beatles and mixed them in with punk and metal in some of his songs. You probably wouldn't be listening to the ambition of the latest OutKast record if the Beatles hadn't made the White Album into a double LP! I've co-written some songs with Paul McCartney and performed with him in concert on two occasions. In 1999, a little time after Linda McCartney's death, Paul did the Concert for Linda, organized by Chrissie Hynde. During the rehearsal, I was singing harmony on a Ricky Nelson song, and Paul called out the next tune: "All My Loving." I said, "Do you want me to take the harmony line the second time round?" And he said, "Yeah, give it a try." I'd only had thirty-five years to learn the part. It was a very poignant performance, witnessed only by the crew and other artists on the bill. At the show, it was very different. The second he sang the opening lines -- "Close your eyes, and I'll kiss you" -- the crowd's reaction was so intense that it all but drowned the song out. It was very thrilling but also rather disconcerting. Perhaps I understood in that moment one of the reasons why the Beatles had to stop performing. The songs weren't theirs anymore. They were everybody's. - Elvis Costello

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan and I started out from different sides of the tracks. When I first heard him, I was already in a band, playing rock & roll. I didn't know a lot of folk music. I wasn't up to speed on the difference he was making as a songwriter. I remember somebody playing "Oxford Town," from The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, for me. I thought, "There's something going on here." His voice seemed interesting to me. But it wasn't until we started playing together that I really understood it. He is a powerful singer and a great musical actor, with many characters in his voice. I could hear the politics in the early songs. It's very exciting to hear somebody singing so powerfully, with something to say. But what struck me was how the street had had such a profound effect on him: coming from Minnesota, setting out on the road and coming into New York. There was a hardness, a toughness, in the way he approached his songs and the characters in them. That was a rebellion, in a certain way, against the purity of folk music. He wasn't pussyfooting around on "Like a Rolling Stone" or "Ballad of a Thin Man." This was the rebel rebelling against the rebellion.

I learned early on with Bob that the people he hung around with were not musicians. They were poets, like Allen Ginsberg. When we were in Europe, there'd be poets coming out of the woodwork. His writing came directly out of a tremendous poetic influence, a license to write in images that weren't in the Tin Pan Alley tradition or typically rock & roll, either. I watched him sing "Desolation Row" and "Mr. Tambourine Man" in those acoustic sets in 1965 and '66. I had never seen anything like it -- how much he could deliver with a guitar and a harmonica, and how people would just take the ride, going through these stories and songs with him.

When he and I went to Nashville in 1966, to work on Blonde on Blonde, it was the first time I'd ever seen a songwriter writing songs on a typewriter. We'd go to the studio, and he'd be finishing up the lyrics to some of the songs we were going to do. I could hear this typewriter -- click, click, click, ring, really fast. He was typing these things out so fast; there was so much to be said. And he'd be changing things during a session. He'd have a new idea and try to incorporate that. That was something else he taught me early on. The Hawks were band musicians. We needed to know where the song was going to go, what the chord changes were, where the bridge was. Bob has never been big on rehearsing. He comes from a place where he just did the songs on acoustic guitar by himself. When we'd play the song with him, it would be, "How do we end it?" And he'd say, "Oh, when it's over, it's over. We'll just stop." We got so we were ready for anything -- and that was a good feeling. We'd think, "OK, this can take a left turn at any minute -- and I'm ready."

More than anything, in my own songwriting, the thing I learned from Bob is that it's OK to break those traditional rules of what songs are supposed to be: the length of a song, how imaginative you could get telling the story. It was great that someone had broken down the gates, opened up the sky to all of the possibilities. One thing that I don't think people realize is that to write the way he does, to get that many ideas into these very distinct melodies, you had to be really good at phrasing. His vocal phrasing was special. He got these characters and images across in a way that didn't feel stiff or forced, with a musical comfort so you could just take the ride and never question it. And a lot of times there was an attitude in his voice that worked for a particular record. I remember when he played Nashville Skyline for me. I was amazed at the character that he had pulled out of the bag for that.

I think Bob has a true passion for the challenge, for coming up with something in the music that makes him feel good, to keep on doing it and doing it, as he does now. The songs Bob is writing now are as good as any songs he's ever written. There's a wonderful honesty in them. He writes about what he sees and feels, about who he is. We spent a lot of time together in the 1970s. We were both living in Malibu and knew what was going on in our respective day-to-day lives. And I know Blood on the Tracks is a reflection of what was happening to him then. When he writes songs, he's telling me things about himself, holding up a mirror -- and I'm seeing it all clearly, like I've never seen it before.

From my knowledge of him, I don't think Bob ever wanted to be more than a good songwriter. When people are like, "Oh, my God, you're having an effect on culture and society" -- I doubt he thinks like that. I don't think Hank Williams understood why his songs were so much more moving than other people's songs. I think Bob is thinking, "I hope I can think of another really good song." He's putting one foot in front of the other and just following his bliss.

But Bob is a great barometer for young singers and songwriters. As soon as they think they've written something good -- "I'm pushing the envelope here, I've made a breakthrough" -- they should listen to one of his songs. He will always stand as the one to measure good work by. That's one of the greatest accomplishments of all. - Robbie Robertson

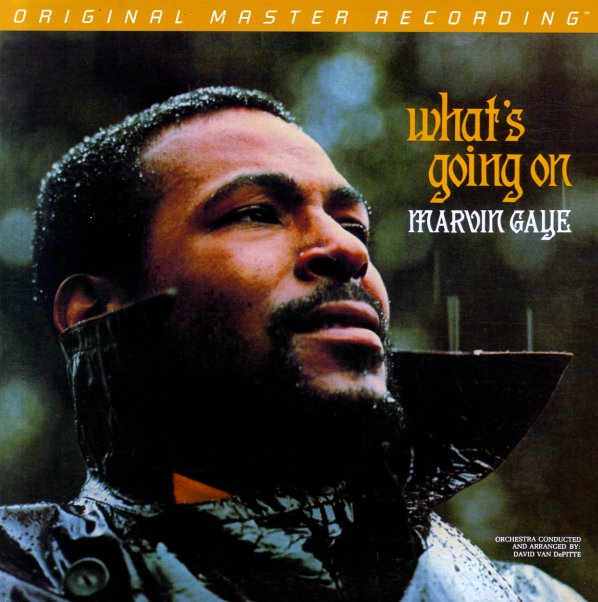

Marvin Gaye

At Motown, Marvin was one of the main characters in the greatest musical story ever told. Prior to that, nothing quite like Motown had ever existed -- all those songwriters, singers, producers working and growing together, part family, part business -- and I doubt seriously if it will ever happen like that again. And there's no question that Marvin will always be a huge part of the Motown legacy.

When Marvin first came to Motown, he was the drummer on all the early hits I had with the Miracles. He and I became close friends -- he was my brother, really -- and I did a lot of production and wrote a lot of songs for him: "Ain't That Peculiar," "I'll Be Doggone." Of course, that means that I spent a lot of time waiting for Marvin. See, Marvin was basically late coming to the studio all the time. But I never minded, because I knew that whenever Marvin did get there, he was going to sing my song in a way that I had never imagined it. He would Marvinize my songs, and I loved it. Marvin could sing anything, from gospel to gutbucket blues, to jazz, to pop.

But Marvin was much more than just a great singer. He was a great record maker, a gifted songwriter, a deep thinker -- a real artist in the true sense. What's Going On is the most profound musical statement in my lifetime. It never gets dated. Listen to it right now -- "Brother, brother, brother/ There's far too many of you dying" -- it's even more poignant than it was when he made it. I still remember when I would go by Marvin's house and he was working on it, he would say, "Smoke, this album is being written by God, and I'm just the instrument that he's writing it through."

Marvin really had it all -- that voice, that soul, that look, too. He was one very handsome man, and he had sex appeal that women were drawn to always. And his music was sexy, not just "Let's Get It On" or "I Want You," but all of it. You couldn't blame women for falling in love with Marvin. Beyond being his friend and his brother, I'm a major Marvin Gaye fan. At the time Marvin was alive, his was my favorite male voice. I said before that when you worked with Marvin, it meant you were waiting for Marvin. But Marvin was always worth the wait. I suppose that in a way, I'm still waiting for Marvin. – Smokey Robinson

U2

I don't buy weekend tickets to Ireland and hang out in front of their gates, but U2 are the only band whose entire catalog I know by heart. The first song on The Unforgettable Fire, "A Sort of Homecoming," I know backward and forward -- it's so rousing, brilliant and beautiful. It's one of the first songs I played to my unborn baby. The first U2 album I ever heard was Achtung Baby. It was 1991, and I was fourteen years old. Before that, I didn't even know what albums were. From that point, I worked backward -- every six months, I'd get to buy a new U2 album. The sound they pioneered -- the driving bass and drums underneath and those ethereal, effects-laden guitar tracks floating out from above -- was nothing that had been heard before. They may be the only good anthemic rock band ever. Certainly they're the best.

What I love most about U2 is that the band is more important than any of their songs or albums. I love that they're best mates and have an integral role in one another's lives as friends. I love the way that they're not interchangeable -- if Larry Mullen Jr. wants to go scuba diving for a week, the rest of the band can't do a thing. U2 -- like Coldplay -- maintain that all songs that appear on their albums are credited to the band. And they are the only band that's been around for twenty years with no member changes and no big splits.

It's amazing that the biggest band in the world has so much integrity and passion in their music. Our society is thoroughly screwed, fame is a ridiculous waste of time, and celebrity culture is disgusting. There are only a few people around brave enough to talk out against it, who use their fame in a good way. And every time I try, I feel like an idiot, because I see Bono actually getting things achieved. While everyone else is swearing at George Bush, Bono is the one who rubs Bush's back and gets a billion dollars for Africa. People can be so cynical -- they don't like do-gooders -- but Bono's attitude is, "I don't care what anybody thinks, I'm going to speak out." He's accomplished so much with Greenpeace, in Sarajevo, at the concert to shut down the Sellafield nuclear plant, and he still runs the gantlet. When the time came for Coldplay to think about fair trade, we took his lead to speak out regardless of what anyone may think. That's what we've learned from U2: You have to be brave enough to be yourself. – Chris Martin

Bruce Springsteen

In many ways, Bruce Springsteen is the embodiment of rock & roll. Combining strains of Appalachian music, rockabilly, blues and R&B, his work epitomizes rock's deepest values: desire, the need for freedom and the search to find yourself. All through his songs there is a generosity and a willingness to portray even the simplest aspects of our lives in a dramatic and committed way.

The first time I heard him play was at a small club, the Bitter End in New York, where he did a guest set. He had this descriptive power -- it was just an amazing display of lyrical prowess. I asked him where he was from, and he sort of grinned and said he was from New Jersey. In those days people used to joke about New Jersey. There was this collective complex that people from New Jersey had about what it meant to be from there, and he just smiled because he knew where he was from.

The next time I saw him play it was with his band, the one with David Sancious in it. I'd never seen anybody do what he was doing: He would play acoustic guitar and dance all over the place, and the guitar wasn't plugged into anything. There wasn't this meticulous need to have every note heard. It was so powerful, and it filled that college gym with so much emotion that it didn't matter if you couldn't hear every note. It was drama, his approach to music, something that he would expand on many times over, but it was there from the beginning.

A year or so later I saw him play in L.A., with Max Weinberg, Clarence Clemons and Steve Van Zandt in the band, and it was even more dramatic -- the use of lights and the way it was staged. There were these events built into the music. I went to see them the second night, and I guess I expected it to be the same thing, but it was completely different. It was obvious that they were drawing on a vocabulary. It was exhilarating, and at the bottom of it all there was all this joy and fun and a sense of brotherhood, of being outsiders who had tremendous power and a story to tell.

Bruce has been unafraid to take on the tasks associated with growing up. He's a family man, with kids and the same values and concerns as working-class Americans. It runs all through his work, the idea of finding that one person and making a life together. Look at "Rosalita": Her mother doesn't like him, her father doesn't like him, but he's come for her. Or in "The River," where he gets Mary pregnant and for his nineteenth birthday he gets a union card and a wedding coat. That night they go to the river and dive in. For those of us who are ambivalent about marriage, the struggle for love in a world of impermanence is summed up by the two of them diving into that river at night. Bruce's songs are filled with these images, but they aren't exclusively the images of working-class people. It just happens to be where he's from.

Bruce has all kinds of influences, from Chuck Berry and Gary "U.S." Bonds to Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie. But he's also a lot like Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and James Dean -- people whose most indistinct utterances have been magnified to communicate volumes. Bruce has always had enormous range in terms of subject and emotion, as well as volume -- his quietest stuff is as quiet as you will ever hear anyone sing, but at his loudest he is, well, he's the loudest. But he's always worked on a very large scale, a scale that is nothing short of heroic. He is one of the few songwriters who works on a scale that is capable of handling the subject of our national grief and the need to find a response to September 11th. His sense of music as a healing power, of band-as-church, has always been there, woven into the fabric of his songs. He's got his feet planted on either side of that great divide between black and white gospel, between blues and country, between rebellion and redemption. – Jackson Browne

Neil Young

There's a rare contradiction in Neil Young's work. He works so hard as a songwriter, and he's written a phenomenal number of perfect songs. And, at the same time, he doesn't give a fuck. That comes from caring about essence. There can be things out of tune and all wild-sounding and not recorded meticulously. And he doesn't care. He's made whole albums that aren't great, and instead of going back to a formula that he knows works, he would rather represent where he is at the time. That's what's so awesome: watching his career wax and wane according to the truth of his character at the moment. It's never phony. It's always real. The truth is not always perfect.