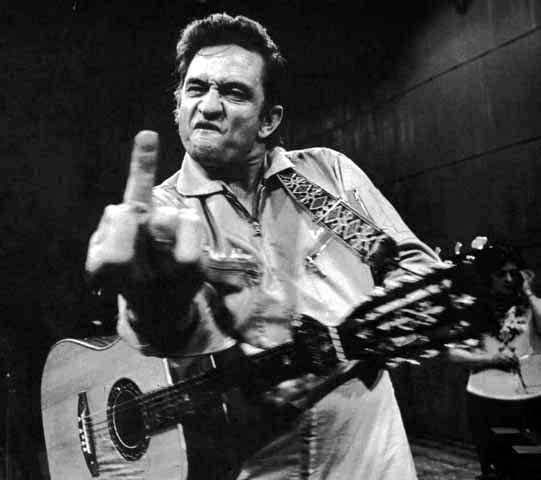

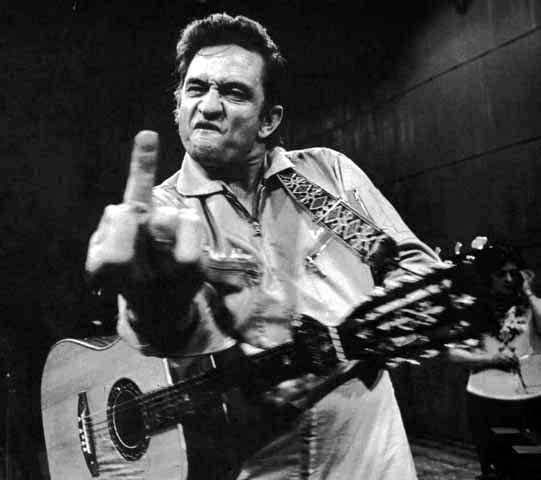

The Johnny Cash biopic is good. Here is Folsom Prison Blues.

First Love

by Wislawa Szymborska

Translated from the Polish

They say

the first love's most important.

That's very romantic,

but not my experience.

Something was and wasn't there between us,

something went on and went away.

My hands never tremble

when I stumble on silly keepsakes

and a sheaf of letters tied with string

— not even ribbon.

Our only meeting after years:

two chairs chatting

at a chilly table.

Other loves

still breathe deep inside me.

This one's too short of breath even to sigh.

Yet just exactly as it is,

it does what the others still can't manage:

unremembered,

not even seen in dreams,

it introduces me to death.

MANAGEMENT

ON NOVEMBER 11th, a few days short of his 96th birthday, Peter Drucker died. The most important management thinker of the past century, he wrote about 40 books (the last, “The Effective Executive in Action” will be published in January) and thousands of articles. He was a guru to the world's corporate elite, not just in his native Europe and his adoptive America, but also in Japan and the developing world (one devoted South Korean businessman even changed his first name to Mr Drucker). And he never rested in his mission to persuade the world that management matters—that, in his own rather portentous formula, “Management is the organ of institutions...the organ that converts a mob into an organisation, and human efforts into performance.”

Did he succeed? The range of his influence was extraordinary. George Bush is a devotee of Mr Drucker's idea of “management by objectives”. (“I had read Peter Drucker,” Karl Rove once told the Atlantic Monthly, “but I'd never seen Drucker until I saw Bush in action.”) Newt Gingrich mentions him in almost every speech. Mr Drucker helped to inspire privatisation—an idea that in the 1980s galvanised Britain's sclerotic economy.

He changed the course of thousands of businesses. He spawned two huge revolutions at General Electric—first when GE followed the radical decentralisation he preached in the 1950s, and again in the 1980s when Jack Welch rebuilt the company around Mr Drucker's belief that it should be first or second in a line of business, or else get out. Yet Mr Drucker is also cited as a muse by both the Salvation Army and the modern mega-church movement. Wherever people grapple with tricky management problems, from big organisations to small ones, from the public sector to the private, and increasingly in the voluntary sector, you can find Mr Drucker's fingerprints.

This is not to say that Mr Drucker was invariably right—or even always sensible. He was given to making sweeping statements that sometimes turned out to be nonsense. He argued, for example, that the great American research universities are “failures” that would soon become “relics”—odd for a man who made so much of the knowledge economy. He was slow to shift his attention from big firms to entrepreneurial start-ups. But he was much more often right than wrong. And even when he was wrong he had a way of being thought-provoking.

The man who became famous as an American management thinker was really a Viennese Jewish intellectual. The author of this article once visited him in his home in Claremont, California—a modest affair when set beside the mansions of most management gurus. His choice of a restaurant for lunch was more modest still. But as Mr Drucker talked it was easy to forget about the giant plastic wagon wheels that decorated the walls or even the execrable food. He talked with his deep, heavy Teutonic accent about meeting Sigmund Freud (as a boy), John Maynard Keynes and Ludwig Wittgenstein (as a student at Cambridge). He said that he liked to keep his mind fresh by taking up a new subject every three or four years (he was heavily immersed in early medieval Paris at the time). The overall effect was rather like listening to Isaiah Berlin channelled by Henry Kissinger.

Mr Drucker was born in 1909 in the Austrian upper middle class—his father was a government official—and educated in Vienna and Germany. He earned a doctorate in international and public law from Frankfurt university in 1931. In normal times this would have led to a distinguished, if predictable, academic career. But those were not normal times—and Mr Drucker was not a man to bow down to the confines of academic disciplines. He spent his 20s trying to avoid Adolf Hitler and drifting among a number of jobs, including banking, consultancy, academic law and journalism (his journalistic career included a spell as the acting editor of a women's page).

Along the way, he became increasingly convinced that the best hope for saving civilisation from barbarism lay in the humdrum science of management. He was too sensitive to the thinness of the crust of civilisation to share the classic liberal faith in the market, but too clear-sighted to embrace the growing fashion for big-government solutions. The man in the grey-flannel suit held out more hope for mankind than either the hidden hand or the gentleman in Whitehall.

He finally found a home in American academia, teaching politics, philosophy and economics. But it was not exactly a happy home. His first two books—“The End of Economic Man” (1939) and “The Future of Industrial Man” (1942)—had their admirers, including Winston Churchill, but they annoyed academic critics by ranging so widely over so many different subjects. This might have sealed his fate as just another discontented academic maverick. But “The Future of Industrial Man” attracted the attention of General Motors—then the world's biggest company—with its passionate insistence that companies had a social dimension as well as an economic purpose.

The car company invited Mr Drucker to paint its portrait—and offered him unique access to GMers from Alfred Sloan down. The resulting book—“The Concept of the Corporation”—changed the young man's life. The book not only became an instant bestseller, in Japan as well as in America, remaining in print ever since. It also helped to create a management fashion for decentralisation. By the 1980s, about three-quarters of American companies had adopted a decentralised model. Mr Drucker later boasted that the book “had an immediate impact on American business, on public service institutions, on government agencies—and none on General Motors.” Mr Drucker the management guru had been born.

Knowledge workers

The two most interesting arguments in “The Concept of the Corporation” actually had little to do with the decentralisation fad. They were to dominate his work.

The first had to do with “empowering” workers. Mr Drucker believed in treating workers as resources rather than just as costs. He was a harsh critic of the assembly-line system of production that then dominated the manufacturing sector—partly because assembly lines moved at the speed of the slowest and partly because they failed to engage the creativity of individual workers. He was equally scathing of managers who simply regarded companies as a way of generating short-term profits. In the late 1990s he turned into one of America's leading critics of soaring executive pay, warning that “in the next economic downturn, there will be an outbreak of bitterness and contempt for the super-corporate chieftains who pay themselves millions.”

The second argument had to do with the rise of knowledge workers. Mr Drucker argued that the world is moving from an “economy of goods” to an economy of “knowledge”—and from a society dominated by an industrial proletariat to one dominated by brain workers. He insisted that this had profound implications for both managers and politicians. Managers had to stop treating workers like cogs in a huge inhuman machine—the idea at the heart of Frederick Taylor's stopwatch management—and start treating them as brain workers. In turn, politicians had to realise that knowledge, and hence education, was the single most important resource for any advanced society.

Yet Mr Drucker also thought that this economy had implications for knowledge workers themselves. They had to come to terms with the fact that they were neither “bosses” nor “workers”, but something in between: entrepreneurs who had responsibility for developing their most important resource, brainpower, and who also needed to take more control of their own careers, including their pension plans.

All this sounds as if Mr Drucker was an exponent of the airy-fairy human-relations school of management. But there was also a “hard” side to his work. Mr Drucker was responsible for inventing one of the rational school of management's most successful products—“management by objectives” (this is the one that Mr Bush still follows).

In one of his most substantial works, “The Practice of Management” (1954), he emphasised the importance of managers and corporations setting clear long-term objectives and then translating those long-term objectives into more immediate goals. He argued that firms should have an elite corps of general managers, who set these long-term objectives, and then a group of more specialised managers.

For his critics (who had a point), this was a retreat from his earlier emphasis on the soft side of management. For Mr Drucker it was all perfectly consistent: if you rely too much on empowerment you risk anarchy, whereas if you rely too much on command-and-control you sacrifice creativity. The trick is for managers to set long-term goals, but then allow their employees to work out ways of achieving those goals.

From early on, Mr Drucker tried to apply his interest in management in a universal way. For instance, he realised that America has no monopoly on management wisdom. This might not sound like much of an insight today, in the light of the Asian miracles. But in 1950s America—when most American managers dismissed Japan as a maker of cheap knickknacks and the rest of Asia as an irrelevance—it was a revelation.

Mr Drucker used his newfound fame in Japan to flesh out his suspicion that Japan was turning itself into an economic powerhouse. (As a sideline he managed to develop a fine collection of Japanese art.) He wrote extensively about Japanese management techniques long before they became popular in America in the 1980s. But he also exported many American techniques to a country that was desperate to learn from Uncle Sam.

More than just a business thinker

If Mr Drucker helped make management a global industry, he also helped push it beyond its business base. He was emphatically a management thinker, not just a business one. He believed that management is “the defining organ of all modern institutions”, not just corporations; and the management school that bears his name at Claremont College recruits a third of its students from outside the business world.

In the public sector, as well as championing privatisation, he helped to inspire the reinventing-government movement that Al Gore promoted with some success in the 1990s. That movement has gone into eclipse at the federal level, but is still forging ahead in some states, such as Massachusetts, where Mitt Romney, the governor, is a powerful supporter.

Some of Mr Drucker's most innovative work was with voluntary and religious institutions (indeed, Mr Bush singled out his contribution to civil institutions when he awarded him the presidential medal of freedom three years ago). Mr Drucker told his clients, who included the American Red Cross and the Girl Scouts of America, that they needed to think more like businesses—albeit businesses that dealt in “changed lives” rather than in maximising profits. Their donors, he warned, would increasingly judge them not on the goodness of their intentions, but on the basis of their results.

One perhaps unexpected example of Druckerism is the modern mega-church movement. He suggested to evangelical pastors that they create a more customer-friendly environment (hold back on the overt religious symbolism and provide plenty of facilities). Bill Hybels, the pastor of the 17,000-strong Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Illinois, has a quotation from Mr Drucker hanging outside his office: “What is our business? Who is our customer? What does the customer consider value?”

Mr Drucker went further than just applying business techniques to managing voluntary organisations. He believed that such entities have many lessons to teach business corporations. They are often much better at engaging the enthusiasm of their volunteers—and they are also better at turning their “customers” into “marketers” for their organisation. These days, business organisations have as much to learn from churches as churches have to learn from them.

What he got wrong

There are three persistent criticisms of Mr Drucker's work. The first is that he was never as good on small organisations—particularly entrepreneurial start-ups—as he was on big ones. “The Concept of the Corporation” was in many ways a fanfare to big organisations: “We know today that in modern industrial production, particularly in modern mass production,” Mr Drucker opined, “the small unit is not only inefficient, it cannot produce at all.” The book helped to launch the “big organisation boom” that dominated business thinking for the next 20 years.

The second criticism is that Mr Drucker's enthusiasm for management by objectives helped to lead business down a dead end. Most of today's best organisations have abandoned this idea—at least in the mechanistic form that it rapidly assumed. They prefer to allow ideas—including ideas for long-term strategies—to bubble up from the bottom and middle of the organisations rather than being imposed from on high. And they tend to eschew the complex management structures of the management-by-objectives era. The reason is that top management is often cut off from the people who know both their markets and their products best (a criticism that certainly rings true in Mr Bush's White House, though that is another story).

Third, Mr Drucker is criticised for being a maverick in the management world—and a maverick who has increasingly been left behind by the increasing rigour of his chosen field. He taught in tiny Claremont rather than at Harvard or Stanford. He never grappled with the rigours of quantitative techniques. There is no single area of academic management theory that he made his own—as Michael Porter did with strategy and Theodore Levitt did with marketing. He would throw out a highly provocative idea—such as the idea that the West has entered a post-capitalist society, thanks to the importance of pension funds—without really clarifying his terms or tying up his arguments.

There is some truth in the first two arguments. Mr Drucker never wrote anything as good as “The Concept of the Corporation” on entrepreneurial start-ups. This is odd, given his personality: this prophet of the “age of organisations” was a quintessential individualist who was happiest ploughing his own furrow. (One of his favourite sayings was, “One either meets or one works.”) It is also remarkable since he spent so much of his life in southern California—a hotbed of individualism and entrepreneurialism that helped to produce the small-business revolution of the 1980s. Mr Drucker's work on management by objectives sits uneasily with his earlier (and later) writing on the importance of knowledge workers and self-directed teams.

But the third argument—that he was too much of a maverick—is both short-sighted and unfair. It is short-sighted because it ignores Mr Drucker's pioneering role in creating the modern profession of management. He produced one of the first systematic studies of a big company. He pioneered the idea that ideas can help galvanise companies. And he helped to make management fashionable with a constant stream of popular writing. It may be over-egging things to claim that Mr Drucker was “the man who invented management”. But he certainly made a unique contribution to the development of the subject.

It is true that he cannot be put into any neat academic pigeonhole: he liked to refer to himself as a “social ecologist” rather than a management theorist, still less a management guru (he once quipped that journalists use the word “guru” only because “charlatan” is too long for a headline). It is true that he eschewed the system-building of some of his fellow academics. And he preferred reading Jane Austen to doing multivariate analysis.

But system-building often produces castles in the air rather than enduring insights. (It is notable that Mr Drucker's most systematic work—on management by objectives—has lasted least well.) Mr Drucker made up for his lack of system with a stream of insights on an extraordinary range of subjects: he was one of the first people to predict, back in the 1950s, that computers would revolutionise business, for example. His reading of history enabled him to see through the fog that clouds less learned minds: he liked to puncture breathless talk of the new age of globalisation by pointing out that companies such as Fiat (founded in 1899) and Siemens (founded in 1847) produced more abroad than at home almost as soon as they got off the ground.

These days management theory is increasingly dominated by academic clones who produce papers on minute subjects in unreadable prose. That certainly does not apply to a man who claimed that the academic course that most influenced him was on, of all things, admiralty law.

The legacy

The biggest problem with evaluating Mr Drucker's influence is that so many of his ideas have passed into conventional wisdom—in other words, that he is the victim of his own success. His writings on the importance of knowledge workers and empowerment may sound a little banal today. But they certainly weren't banal when he first dreamed them up in the 1940s, or when they were first put in to practice in the Anglo-Saxon world in the 1980s. Remember the way that many British bosses scoffed when Japanese carmakers set up factories in Britain and told their Geordie workers that they had to think as well as rivet, weld and hammer?

Moreover, Mr Drucker continued to produce new ideas up until his 90s. His work on the management of voluntary organisations—particularly religious organisations—remained at the cutting edge. America's business academics have only just begun to look seriously at the organisational transformation that he helped to pioneer.

Mr Drucker has a way of getting the last word. Richard Nixon once began a pep talk to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare with a side-swipe at him. “Mr Drucker says that modern government can do only two things well: wage war and inflate the currency. It's the aim of my administration to prove Mr Drucker wrong.” In retrospect, Mr Nixon failed even at those potentially achievable tasks.

Asked which management books he paid attention to, Bill Gates once replied, “Well, Drucker of course,” before citing a few lesser mortals. Management theory has not evolved into the world's most rigorous or enticing intellectual discipline. But in Peter Drucker it at least found a champion whom every educated person should take the trouble to read.

First Love

by Wislawa Szymborska

Translated from the Polish

They say

the first love's most important.

That's very romantic,

but not my experience.

Something was and wasn't there between us,

something went on and went away.

My hands never tremble

when I stumble on silly keepsakes

and a sheaf of letters tied with string

— not even ribbon.

Our only meeting after years:

two chairs chatting

at a chilly table.

Other loves

still breathe deep inside me.

This one's too short of breath even to sigh.

Yet just exactly as it is,

it does what the others still can't manage:

unremembered,

not even seen in dreams,

it introduces me to death.

MANAGEMENT

ON NOVEMBER 11th, a few days short of his 96th birthday, Peter Drucker died. The most important management thinker of the past century, he wrote about 40 books (the last, “The Effective Executive in Action” will be published in January) and thousands of articles. He was a guru to the world's corporate elite, not just in his native Europe and his adoptive America, but also in Japan and the developing world (one devoted South Korean businessman even changed his first name to Mr Drucker). And he never rested in his mission to persuade the world that management matters—that, in his own rather portentous formula, “Management is the organ of institutions...the organ that converts a mob into an organisation, and human efforts into performance.”

Did he succeed? The range of his influence was extraordinary. George Bush is a devotee of Mr Drucker's idea of “management by objectives”. (“I had read Peter Drucker,” Karl Rove once told the Atlantic Monthly, “but I'd never seen Drucker until I saw Bush in action.”) Newt Gingrich mentions him in almost every speech. Mr Drucker helped to inspire privatisation—an idea that in the 1980s galvanised Britain's sclerotic economy.

He changed the course of thousands of businesses. He spawned two huge revolutions at General Electric—first when GE followed the radical decentralisation he preached in the 1950s, and again in the 1980s when Jack Welch rebuilt the company around Mr Drucker's belief that it should be first or second in a line of business, or else get out. Yet Mr Drucker is also cited as a muse by both the Salvation Army and the modern mega-church movement. Wherever people grapple with tricky management problems, from big organisations to small ones, from the public sector to the private, and increasingly in the voluntary sector, you can find Mr Drucker's fingerprints.

This is not to say that Mr Drucker was invariably right—or even always sensible. He was given to making sweeping statements that sometimes turned out to be nonsense. He argued, for example, that the great American research universities are “failures” that would soon become “relics”—odd for a man who made so much of the knowledge economy. He was slow to shift his attention from big firms to entrepreneurial start-ups. But he was much more often right than wrong. And even when he was wrong he had a way of being thought-provoking.

The man who became famous as an American management thinker was really a Viennese Jewish intellectual. The author of this article once visited him in his home in Claremont, California—a modest affair when set beside the mansions of most management gurus. His choice of a restaurant for lunch was more modest still. But as Mr Drucker talked it was easy to forget about the giant plastic wagon wheels that decorated the walls or even the execrable food. He talked with his deep, heavy Teutonic accent about meeting Sigmund Freud (as a boy), John Maynard Keynes and Ludwig Wittgenstein (as a student at Cambridge). He said that he liked to keep his mind fresh by taking up a new subject every three or four years (he was heavily immersed in early medieval Paris at the time). The overall effect was rather like listening to Isaiah Berlin channelled by Henry Kissinger.

Mr Drucker was born in 1909 in the Austrian upper middle class—his father was a government official—and educated in Vienna and Germany. He earned a doctorate in international and public law from Frankfurt university in 1931. In normal times this would have led to a distinguished, if predictable, academic career. But those were not normal times—and Mr Drucker was not a man to bow down to the confines of academic disciplines. He spent his 20s trying to avoid Adolf Hitler and drifting among a number of jobs, including banking, consultancy, academic law and journalism (his journalistic career included a spell as the acting editor of a women's page).

Along the way, he became increasingly convinced that the best hope for saving civilisation from barbarism lay in the humdrum science of management. He was too sensitive to the thinness of the crust of civilisation to share the classic liberal faith in the market, but too clear-sighted to embrace the growing fashion for big-government solutions. The man in the grey-flannel suit held out more hope for mankind than either the hidden hand or the gentleman in Whitehall.

He finally found a home in American academia, teaching politics, philosophy and economics. But it was not exactly a happy home. His first two books—“The End of Economic Man” (1939) and “The Future of Industrial Man” (1942)—had their admirers, including Winston Churchill, but they annoyed academic critics by ranging so widely over so many different subjects. This might have sealed his fate as just another discontented academic maverick. But “The Future of Industrial Man” attracted the attention of General Motors—then the world's biggest company—with its passionate insistence that companies had a social dimension as well as an economic purpose.

The car company invited Mr Drucker to paint its portrait—and offered him unique access to GMers from Alfred Sloan down. The resulting book—“The Concept of the Corporation”—changed the young man's life. The book not only became an instant bestseller, in Japan as well as in America, remaining in print ever since. It also helped to create a management fashion for decentralisation. By the 1980s, about three-quarters of American companies had adopted a decentralised model. Mr Drucker later boasted that the book “had an immediate impact on American business, on public service institutions, on government agencies—and none on General Motors.” Mr Drucker the management guru had been born.

Knowledge workers

The two most interesting arguments in “The Concept of the Corporation” actually had little to do with the decentralisation fad. They were to dominate his work.

The first had to do with “empowering” workers. Mr Drucker believed in treating workers as resources rather than just as costs. He was a harsh critic of the assembly-line system of production that then dominated the manufacturing sector—partly because assembly lines moved at the speed of the slowest and partly because they failed to engage the creativity of individual workers. He was equally scathing of managers who simply regarded companies as a way of generating short-term profits. In the late 1990s he turned into one of America's leading critics of soaring executive pay, warning that “in the next economic downturn, there will be an outbreak of bitterness and contempt for the super-corporate chieftains who pay themselves millions.”

The second argument had to do with the rise of knowledge workers. Mr Drucker argued that the world is moving from an “economy of goods” to an economy of “knowledge”—and from a society dominated by an industrial proletariat to one dominated by brain workers. He insisted that this had profound implications for both managers and politicians. Managers had to stop treating workers like cogs in a huge inhuman machine—the idea at the heart of Frederick Taylor's stopwatch management—and start treating them as brain workers. In turn, politicians had to realise that knowledge, and hence education, was the single most important resource for any advanced society.

Yet Mr Drucker also thought that this economy had implications for knowledge workers themselves. They had to come to terms with the fact that they were neither “bosses” nor “workers”, but something in between: entrepreneurs who had responsibility for developing their most important resource, brainpower, and who also needed to take more control of their own careers, including their pension plans.

All this sounds as if Mr Drucker was an exponent of the airy-fairy human-relations school of management. But there was also a “hard” side to his work. Mr Drucker was responsible for inventing one of the rational school of management's most successful products—“management by objectives” (this is the one that Mr Bush still follows).

In one of his most substantial works, “The Practice of Management” (1954), he emphasised the importance of managers and corporations setting clear long-term objectives and then translating those long-term objectives into more immediate goals. He argued that firms should have an elite corps of general managers, who set these long-term objectives, and then a group of more specialised managers.

For his critics (who had a point), this was a retreat from his earlier emphasis on the soft side of management. For Mr Drucker it was all perfectly consistent: if you rely too much on empowerment you risk anarchy, whereas if you rely too much on command-and-control you sacrifice creativity. The trick is for managers to set long-term goals, but then allow their employees to work out ways of achieving those goals.

From early on, Mr Drucker tried to apply his interest in management in a universal way. For instance, he realised that America has no monopoly on management wisdom. This might not sound like much of an insight today, in the light of the Asian miracles. But in 1950s America—when most American managers dismissed Japan as a maker of cheap knickknacks and the rest of Asia as an irrelevance—it was a revelation.

Mr Drucker used his newfound fame in Japan to flesh out his suspicion that Japan was turning itself into an economic powerhouse. (As a sideline he managed to develop a fine collection of Japanese art.) He wrote extensively about Japanese management techniques long before they became popular in America in the 1980s. But he also exported many American techniques to a country that was desperate to learn from Uncle Sam.

More than just a business thinker

If Mr Drucker helped make management a global industry, he also helped push it beyond its business base. He was emphatically a management thinker, not just a business one. He believed that management is “the defining organ of all modern institutions”, not just corporations; and the management school that bears his name at Claremont College recruits a third of its students from outside the business world.

In the public sector, as well as championing privatisation, he helped to inspire the reinventing-government movement that Al Gore promoted with some success in the 1990s. That movement has gone into eclipse at the federal level, but is still forging ahead in some states, such as Massachusetts, where Mitt Romney, the governor, is a powerful supporter.

Some of Mr Drucker's most innovative work was with voluntary and religious institutions (indeed, Mr Bush singled out his contribution to civil institutions when he awarded him the presidential medal of freedom three years ago). Mr Drucker told his clients, who included the American Red Cross and the Girl Scouts of America, that they needed to think more like businesses—albeit businesses that dealt in “changed lives” rather than in maximising profits. Their donors, he warned, would increasingly judge them not on the goodness of their intentions, but on the basis of their results.

One perhaps unexpected example of Druckerism is the modern mega-church movement. He suggested to evangelical pastors that they create a more customer-friendly environment (hold back on the overt religious symbolism and provide plenty of facilities). Bill Hybels, the pastor of the 17,000-strong Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Illinois, has a quotation from Mr Drucker hanging outside his office: “What is our business? Who is our customer? What does the customer consider value?”

Mr Drucker went further than just applying business techniques to managing voluntary organisations. He believed that such entities have many lessons to teach business corporations. They are often much better at engaging the enthusiasm of their volunteers—and they are also better at turning their “customers” into “marketers” for their organisation. These days, business organisations have as much to learn from churches as churches have to learn from them.

What he got wrong

There are three persistent criticisms of Mr Drucker's work. The first is that he was never as good on small organisations—particularly entrepreneurial start-ups—as he was on big ones. “The Concept of the Corporation” was in many ways a fanfare to big organisations: “We know today that in modern industrial production, particularly in modern mass production,” Mr Drucker opined, “the small unit is not only inefficient, it cannot produce at all.” The book helped to launch the “big organisation boom” that dominated business thinking for the next 20 years.

The second criticism is that Mr Drucker's enthusiasm for management by objectives helped to lead business down a dead end. Most of today's best organisations have abandoned this idea—at least in the mechanistic form that it rapidly assumed. They prefer to allow ideas—including ideas for long-term strategies—to bubble up from the bottom and middle of the organisations rather than being imposed from on high. And they tend to eschew the complex management structures of the management-by-objectives era. The reason is that top management is often cut off from the people who know both their markets and their products best (a criticism that certainly rings true in Mr Bush's White House, though that is another story).

Third, Mr Drucker is criticised for being a maverick in the management world—and a maverick who has increasingly been left behind by the increasing rigour of his chosen field. He taught in tiny Claremont rather than at Harvard or Stanford. He never grappled with the rigours of quantitative techniques. There is no single area of academic management theory that he made his own—as Michael Porter did with strategy and Theodore Levitt did with marketing. He would throw out a highly provocative idea—such as the idea that the West has entered a post-capitalist society, thanks to the importance of pension funds—without really clarifying his terms or tying up his arguments.

There is some truth in the first two arguments. Mr Drucker never wrote anything as good as “The Concept of the Corporation” on entrepreneurial start-ups. This is odd, given his personality: this prophet of the “age of organisations” was a quintessential individualist who was happiest ploughing his own furrow. (One of his favourite sayings was, “One either meets or one works.”) It is also remarkable since he spent so much of his life in southern California—a hotbed of individualism and entrepreneurialism that helped to produce the small-business revolution of the 1980s. Mr Drucker's work on management by objectives sits uneasily with his earlier (and later) writing on the importance of knowledge workers and self-directed teams.

But the third argument—that he was too much of a maverick—is both short-sighted and unfair. It is short-sighted because it ignores Mr Drucker's pioneering role in creating the modern profession of management. He produced one of the first systematic studies of a big company. He pioneered the idea that ideas can help galvanise companies. And he helped to make management fashionable with a constant stream of popular writing. It may be over-egging things to claim that Mr Drucker was “the man who invented management”. But he certainly made a unique contribution to the development of the subject.

It is true that he cannot be put into any neat academic pigeonhole: he liked to refer to himself as a “social ecologist” rather than a management theorist, still less a management guru (he once quipped that journalists use the word “guru” only because “charlatan” is too long for a headline). It is true that he eschewed the system-building of some of his fellow academics. And he preferred reading Jane Austen to doing multivariate analysis.

But system-building often produces castles in the air rather than enduring insights. (It is notable that Mr Drucker's most systematic work—on management by objectives—has lasted least well.) Mr Drucker made up for his lack of system with a stream of insights on an extraordinary range of subjects: he was one of the first people to predict, back in the 1950s, that computers would revolutionise business, for example. His reading of history enabled him to see through the fog that clouds less learned minds: he liked to puncture breathless talk of the new age of globalisation by pointing out that companies such as Fiat (founded in 1899) and Siemens (founded in 1847) produced more abroad than at home almost as soon as they got off the ground.

These days management theory is increasingly dominated by academic clones who produce papers on minute subjects in unreadable prose. That certainly does not apply to a man who claimed that the academic course that most influenced him was on, of all things, admiralty law.

The legacy

The biggest problem with evaluating Mr Drucker's influence is that so many of his ideas have passed into conventional wisdom—in other words, that he is the victim of his own success. His writings on the importance of knowledge workers and empowerment may sound a little banal today. But they certainly weren't banal when he first dreamed them up in the 1940s, or when they were first put in to practice in the Anglo-Saxon world in the 1980s. Remember the way that many British bosses scoffed when Japanese carmakers set up factories in Britain and told their Geordie workers that they had to think as well as rivet, weld and hammer?

Moreover, Mr Drucker continued to produce new ideas up until his 90s. His work on the management of voluntary organisations—particularly religious organisations—remained at the cutting edge. America's business academics have only just begun to look seriously at the organisational transformation that he helped to pioneer.

Mr Drucker has a way of getting the last word. Richard Nixon once began a pep talk to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare with a side-swipe at him. “Mr Drucker says that modern government can do only two things well: wage war and inflate the currency. It's the aim of my administration to prove Mr Drucker wrong.” In retrospect, Mr Nixon failed even at those potentially achievable tasks.

Asked which management books he paid attention to, Bill Gates once replied, “Well, Drucker of course,” before citing a few lesser mortals. Management theory has not evolved into the world's most rigorous or enticing intellectual discipline. But in Peter Drucker it at least found a champion whom every educated person should take the trouble to read.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home