FILM

Movies to rent this weekend:

CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS

"This is private, so if you're not me, you shouldn't be watching." So warns David Friedman into a video camera as he records his dew-eyed rantings regarding the sex scandal that was devouring his family. At first you feel like a guilty voyeur to witness such raw emotions, but then you think: Wait, who else could have given the maker of "Capturing the Friedmans" the tape?

The contradiction is typical of the Friedman family and Andrew Jarecki's disturbing, multilayered, compulsively watchable documentary. Every time you think you have a handle on who these people are, what this story is, some new piece of information, usually ugly, gives you a fresh case of mental whiplash.

Appearances are deceiving, and the Friedmans are obsessed with making them. Apparently no moment was too intimate or uncomfortable for someone to turn on the video camera or tape machine.

What we see and hear is the implosion of a formerly respectable suburban family. What we experience is more complex: a challenge to our sense that the truth is ultimately knowable if you just dig deep enough. Here the truth is more like a cloud blown apart by the crosswinds of memory, recorded images, group psychology, imagination, repression and secrets that may remain forever elusive.

On the surface Arnold and Elaine Friedman are living an unextraordinary life with sons David, Seth and Jesse in the affluent Long Island town of Great Neck when police bust Arnold, an award-winning schoolteacher, for possession of a child pornography magazine. As detectives recall, Arnold insists there's just the one magazine - until they find a stash tucked behind the piano.

Like a loose thread pulling apart a sweater, Arnold's claims and the family members' lives unravel. Investigators canvass the neighborhood with questions about the children's computer class that Arnold taught in his basement, and soon Arnold is arrested on child sex-abuse charges - as is his youngest son, 18-year-old Jesse.

All of these events are recounted in the film's opening minutes, yet the story continues to develop and deepen in surprising, suspenseful ways. Jarecki masterfully interweaves his own after-the-fact interviews with TV news coverage of the events and the Friedmans' own stash of home movies, videos and audio tapes. (Jarecki initially intended to make a documentary about David Friedman as New York City's most popular birthday-party clown until David related his family's story and offered the tapes and access in an effort to set the record straight.)

The narrative is clear and moves along briskly, even as it explores a great range of complex issues. Arnold and Jesse protest their innocence, Jesse louder than Arnold, David loudest of all as he stridently supports his father and viciously tears into his mother for expressing any doubts.

The reserved but blunt Elaine, isolated among the tight-knit males in her household, doesn't know what to believe as she learns that her 33-year marriage has been built on a foundation of lies. ("There was nothing between us but the children we yelled at," she says in retrospect.) We come to share her confusion.

The vivid accounts of computer-class assaults are undermined by an almost total lack of either physical evidence or previous complaints of abuse, leading one investigative journalist to inquire whether the entire case is built on community hysteria and the detectives' leading questions.

Jarecki allows his own interviews' wholly contradictory accounts to smack up against one another. One former student describing Arnold's basement sessions as nothing more than a boring computer class is followed by the lead investigator characterizing them as a "free-for-all." At first this lack of resolution is frustrating, like Jarecki owes it to us to solve this case in a way that investigators and journalists couldn't. But some facts may never be known, and others exist in such subjective places that they're beyond reconciliation.

One telling moment comes when David says he doesn't remember the night before Jesse's final court appearance except for what's on the family videotape. What he sees becomes his version of truth.

The same is true for this movie's viewers, who are sure to develop their own theories to make sense of the events. "Capturing the Friedmans" follows Arnold's and Jesse's cases through the court system and beyond (I won't give away what happens here), and we come to question our responses to just about everyone on screen. On the surface David comes across as the most unhinged of the Friedmans, while Arnold remains mild-mannered, Jesse relatively cool-headed.

"Capturing the Friedmans," which won the Grand Jury Prize at January's Sundance Film Festival, is a family drama that takes on an epic, Shakespearean scope. The more you learn, the more questions you have about life in that Great Neck house. Leo Tolstoy wrote that "every unhappy family is unhappy in its own fashion," but not even he could have invented the Friedmans.

SPELLBOUND

On its most basic level, Jeff Blitz's Spellbound (ThinkFilm) documents the 1999 nerd Olympics: 9 million nationwide spelling-bee contestants reduced to 249 finalists reduced to one winner. But the contest turns out to have a deeper resonance than if the sport had been merely physical: Among other things, mastery of the English language becomes a means of affirming one's American-ness. The movie is chiefly a portrait of eight aspiring contestants and their families. The first half introduces them singly in their hometowns: five girls and three boys from all over the country, from different races and economic classes—Angela, Nupur, Ted, Emily, Ashley, Neil, April, and wacky Harry. The second half is the bee itself, in Washington, D.C., where Blitz shows them knocked off, one by one, as in Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None—a favorite of the director's. But these kids aren't expendable drawing-room-mystery victims: It's devastating to watch their stabs of grief when they misspell obscure words (care for a hellebore, anyone?) and the bell goes ding! The movie becomes a nail-biter, the audience hanging on every letter. Who could have anticipated that a spelling competition would yield such a heartbreaking thriller?

You know that the director is onto something with the very first girl, Angela, whose father, Ubaldo, a ranch manager in Texas, speaks no English: The family crossed illegally into the United States from Mexico before she was born. Blitz doesn't sit the father down, the way he will the other parents, as if sensing that a straightforward interview would diminish the man. His uninsistent camera shows Ubaldo traipsing around the ranch, his domain, while his older son explains the risk his dad took so that his children would have an education. Fueled by little more than her parents' dreams, the gangly, giddy Angela is the best speller in her part of Texas—and the family will go to Washington for the first time in their lives.

You'll wonder how Blitz can top Angela, yet almost all these kids hook you on the same level. Nupur is the daughter of Indian immigrants—whose children, says her English teacher, have "a great work ethic." Then there's a cut to Nupur, sawing determinedly on her violin, serious beyond words. Blitz, who shot most of the movie himself on digital video, is a natural at framing these people in a way that captures their glorious individuality yet gives their lives a powerful social context. "You don't get second chances in India the way you do in America," says Nupur's father. And this is Nupur's second chance: The year before, she got knocked out of the nationals in the third round. This year, three local boys do their best to psych her out in the regional bee. But Nupur is unfazeable. The local Tampa, Fla. Hooters celebrates her regional win on its sign: "Congradu tions Nupur."

It's no wonder that the immigrant motif emerges so strongly in Spellbound: This melting-pot nation has a melting-pot language. English has roots in both German and Latin/French, with regular vocabulary infusions from sundry immigrant populations. Mastering its spelling requires both prodigious memorization and a grasp of each word's origins. Distress isn't limited to non-native speakers.

To select his subjects, Blitz and his co-producer, Sean Welch, reportedly combed lists of returning regional champions and picked the brains of countless officials and coaches. The order of the stories is significant, with the worldly, confident Nupur followed by Ted, a rural Missouri kid whose sense of isolation is palpable. "There are a couple of smart kids in my class but not many," he says—not sounding snotty, just lonely. Then it's on to the well-to-do Emily, who has a nice Connecticut home, an au pair, and a warmly supportive community; and Ashley, an African-American girl in southeast Washington, D.C., who has little community support or recognition. Ashley's mother sits smoking at her kitchen table, listing the obstacles her daughter has had to overcome, bitter over the lack of attention: The winner of the Washington metro bee, Ashley doesn't even have a trophy. But the girl herself—dressed in immaculate white—is radiant. "I'm a prayer warrior," she says. "I just can't stop praying. I rise above all my problems." Trying to convince herself as much as Blitz's camera, Ashley makes you want to cry.

In wealthy San Clemente, Calif., we don't see much of Neil—the focus is on his Indian father, whose children are vessels for his seemingly boundless ambition. He loves America: "If you work hard, you'll make it," he avers, and he has Neil working superhumanly hard, drilling him endlessly and hiring tutors in French, Spanish, and German to supplement his school's program in Latin. When we finally meet Neil, the kid seems barely conscious—diffident, almost robotic in his obedience. You know he'd rather be shooting hoops. Blitz follows the most high-pressure dad with a sweetly pessimistic one. In Ambler, Pa., cute, doleful April studies by herself from a battered unabridged dictionary while her father, owner of the rundown "Easy Street Pub," describes himself as "not a real success story," and her chipper mother says, "I can't even pronounce these words. It's rather sad." Surveying her own chances, April confesses, "I don't expect to get past the first round tomorrow." (Of course, I was rooting for April.) The final subject is New Jersey's irrepressible Harry—a twitchy, compulsively prattling uber-geek who tugs at the microphone ("Is this thing edible?") and nearly brings the national bee to a halt.

It's understandable that we root for the less privileged kids because they've made their own way in the world—but I wish that Blitz didn't show us Connecticut Emily trotting on a horse to reinforce the point that she has money. That said, Emily ultimately comes off as a nice girl with a healthy attitude. It's a measure of Blitz's humanism that even Neil's overbearing father has moments of grace. You can't hate him when you see him rocking in prayer for his son to succeed.

Spellbound is a gorgeous weave. When the contestants take the stage, the editor, Yana Gorskaya, cuts fluidly from the kids to their parents—often doubled over with anxiety—and back to the harrowing recitation of letters. Daniel Hulsizer's simple, plinking chords remind you of "Chopsticks" or a child's building blocks: It's the perfect music for this innocent—yet unnerving—milieu. The real-time tension is so strong that it's a relief when the movie takes a breather to meet contest officials and past spelling champions, among them the very first winner, from 1925. They remember their own sense of monklike isolation while they studied, the bond they felt to other social misfits when they arrived at the national finals, and their Olympian pride in victory.

Since seeing Spellbound, I've had many conversations with friends and colleagues about their spelling bee experiences. In the early '70s, I was in the last little group of spellers at my local Connecticut bee but got nailed—symbolically, it has been suggested—by the word "responsibility." My wife, only a decade before she'd embark on thousands of hours of therapy, flamed out on the word "psychiatrist." In Spellbound, Emily hates the word that knocked her out of the '98 bee and says that before it's all over, "I'm probably gonna hate one more word." The brother of a contestant who spells "distractible" with an "a" instead of an "i" insists, "I still think he spelled it right."

There is astonishing skill in Spellbound, but there are also accidents that seem blessed. It's almost like a novel when poor Ashley, the prayer warrior, freezes in terror on hearing the word "ecclesiastical," and when the Indian-American Neil, his head overstuffed with Latin, French, Spanish, and German, registers nothing but bewilderment when asked to spell "Darjeeling." The winner finishes with "logorrhea," which must be someone at the bee's idea of a grand joke. It sounds corny, but I had a hard time seeing any of these kids as losers—and a harder time figuring out how this deeply generous American documentary could have lost the Academy Award to Bowling for Columbine. Is it fair to ask whether most of the voters saw Spellbound? Or would that be irresponseble?

SWIMMING POOL

French director Francois Ozon doesn't like to repeat himself. His last film, 8 Women, was a theatrical, rather campy piece of fluff starring la crème de la crème of contemporary Gallic actresses. Before that came Under the Sand, an unsettling drama about a woman (Charlotte Rampling, giving perhaps her finest screen performance) who loses her grip on reality in the wake of her husband's disappearance. That film was preceded by Water Drops on Burning Rocks, a perverse psychosexual farce adapted from a play by the late German wunderkind Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Ozon's latest offering turns another 180 degrees. A delicious little thriller about an uptight, ill-humored English mystery writer who becomes enmeshed in murder, Swimming Pool is at once comical, contrary, resourceful and ambiguous. Only after it has ended does one realize that its salient characteristic is actually playfulness.

In her second collaboration with Ozon, Rampling stars as Sarah Morton, a British crime novelist whose repeated success has done nothing to improve her sour disposition. Bored with her own exceedingly popular literary creation, Sarah wants to stretch her artistic muscles, a desire discouraged by her editor and sometime lover John (Charles Dance), who is all too familiar with his client's prickly personality and demands for attention. John suggests that Sarah take a holiday and offers her the use of his home in the south of France. After initial grousing, she accepts.

It turns out to be just what the doctor ordered, a beautiful, quiet country home, peaceful and sunny, the perfect environment for Sarah's work. Her tranquility is almost immediately interrupted, however, by the unexpected arrival of John's teen-age French daughter Julie (another Ozon favorite, Ludivine Sagnier). The product of one of John's many extramarital liaisons, Julie is sexy, nonchalant and completely uninhibited. She lounges around the swimming pool topless and sleeps with a succession of unsuitable men. When her attempts to get along with Sarah are met with undisguised animosity, she stops trying.

Sarah's curiosity about Julie, however, grows. She takes to voyeuristically watching the young woman, going so far as to riffle through her diary. In an even more shocking lapse of ethics, Sarah pilfers passages from the diary for her new novel.

Giving away more of the plot would be unfair to the movie. While some of what transpires feels outlandish and even artificial, everything falls into place by the time the story draws to a close. And that's no mean feat.

Both actresses are superb. The normally sensual Rampling looks appropriately dour in unfashionable dresses and sensible shoes, but it is her clenched jaw, erect bearing and purposeful strides that so perfectly communicate her petulant nature and disdainful attitude toward her housemate. A scene in which she attacks a plate of profiteroles in a passive-aggressive rage is wonderful.

With her perfect breasts, pouty Lolita-esque posture and enviable lack of self-consciousness, Sagnier manages to convey a wide range of seemingly contradictory emotions and qualities: brashness, shyness, confidence, vulnerability, wanton sexuality, persuasive innocence. While Julie is supposed to be all of these things, it is difficult to think of another young actress who could suggest such conflicting traits so convincingly and in such a sympathetic manner.

Swimming Pool is Ozon's first English-language film (though a quarter of it is in French--subtitled, of course). Contributing greatly to the picture's overall effectiveness is Phillipe Rombi's Hitchcock-flavored score, a chilling little melody that crops up at infrequent intervals like signposts along a deserted highway, warning viewers of something off-kilter just beyond the bend.

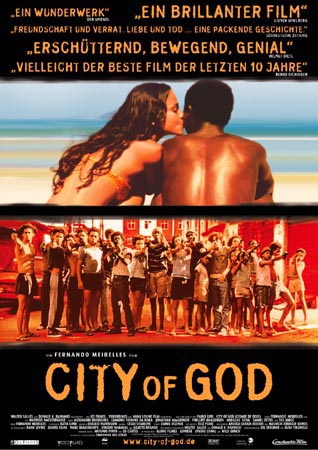

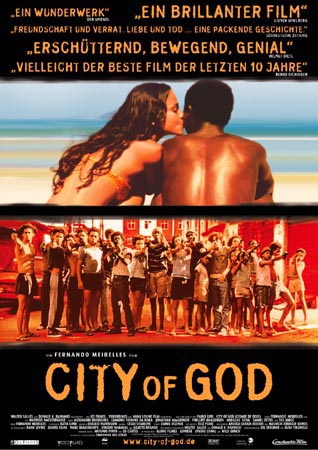

CITY OF GOD

FIRST-TIME director Fernando Meirelles' "City of God" is like a bomb exploding in a fireworks factory: It's fierce and shocking and dazzling and wonderful. It opens with an absconding chicken, hot-footing it through a Rio de Janeiro slum, chased by a pack of gun-wielding teens firing off salvos with abandon. This place is called Cidade de Deus, or City of God - a misnomer if ever there was one, because it looks a lot like hell, and guns are as omnipresent as drugs.

The level of cruelty is bone-chilling, as seething hatreds fester and trigger-happy kids kill each other, but the sheer brilliance of Meirelles' filmmaking is in presenting the ultra-violence in a way that is neither heavy-handed nor blasé. Consider also the fact that Brazil's foremost director of commercials infuses his thoroughly engaging, character-heavy story with wicked humor and a truckload of style, and this debut marks him as one to watch. Screenwriter Braulio Mantovani has done a superb job adapting Paulo Lin's fact-based novel for the screen - no easy task, as Lin's book is an epic that spans three decades and features hundreds of characters.

The cast of mostly amateurs is exceptional, fully inhabiting the myriad characters who people this non-linear film, each one telling a different, interlocking story and each one unforgettable. Backtracking from that bravura opening scene to the 1960s - when the housing project was a moral vacuum, but not yet the diabolical gangland it would become - we meet two 11-year-old kids who will grow to take divergent paths: Rocket (Luis Otavio), a sensitive kid looking to escape the menace of the streets, and Lil Dice (Douglas Silva), a boy with a bloodlust that's shocking in its purity.

Cut to the '70s, and Lil Dice has become Lil Z (Leandro Firmino da Hora), the most feared drug dealer in the city, heading an army of killers as young as 9. When Lil Z gratuitously rapes the girlfriend of Knockout Ned (Seu Jorge), one of the few good guys in this wretched hellhole, Ned is bent on revenge. Ned goes over to the dark side, joining forces with Lil Z's rival drug dealer, Carrot (Matheus Nachtergaele), and, by the 1980s, the two warring gangs have begun tearing the city apart. Rocket (now played by Alexandre Rodrigues), meanwhile, has picked up a camera and has unparalleled access to no man's land. His pictures start landing on the front page of the newspaper.

Cinematographer Cesar Charlone illuminates the sun-drenched war zone with a golden hue and Meirelles' extraordinarily assured visual maneuvers (jump cuts, split screens, video capture, fast motion and scenes of carnage shot from on high, à la "Taxi Driver") make the frenzied action burn beneath a soundscape of funky samba rhythms and a blazing sun. "City of God," Brazil's official Oscar entry, is that rare film that manages to be seductively entertaining without ever compromising its authenticity and power.

Movies to rent this weekend:

CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS

"This is private, so if you're not me, you shouldn't be watching." So warns David Friedman into a video camera as he records his dew-eyed rantings regarding the sex scandal that was devouring his family. At first you feel like a guilty voyeur to witness such raw emotions, but then you think: Wait, who else could have given the maker of "Capturing the Friedmans" the tape?

The contradiction is typical of the Friedman family and Andrew Jarecki's disturbing, multilayered, compulsively watchable documentary. Every time you think you have a handle on who these people are, what this story is, some new piece of information, usually ugly, gives you a fresh case of mental whiplash.

Appearances are deceiving, and the Friedmans are obsessed with making them. Apparently no moment was too intimate or uncomfortable for someone to turn on the video camera or tape machine.

What we see and hear is the implosion of a formerly respectable suburban family. What we experience is more complex: a challenge to our sense that the truth is ultimately knowable if you just dig deep enough. Here the truth is more like a cloud blown apart by the crosswinds of memory, recorded images, group psychology, imagination, repression and secrets that may remain forever elusive.

On the surface Arnold and Elaine Friedman are living an unextraordinary life with sons David, Seth and Jesse in the affluent Long Island town of Great Neck when police bust Arnold, an award-winning schoolteacher, for possession of a child pornography magazine. As detectives recall, Arnold insists there's just the one magazine - until they find a stash tucked behind the piano.

Like a loose thread pulling apart a sweater, Arnold's claims and the family members' lives unravel. Investigators canvass the neighborhood with questions about the children's computer class that Arnold taught in his basement, and soon Arnold is arrested on child sex-abuse charges - as is his youngest son, 18-year-old Jesse.

All of these events are recounted in the film's opening minutes, yet the story continues to develop and deepen in surprising, suspenseful ways. Jarecki masterfully interweaves his own after-the-fact interviews with TV news coverage of the events and the Friedmans' own stash of home movies, videos and audio tapes. (Jarecki initially intended to make a documentary about David Friedman as New York City's most popular birthday-party clown until David related his family's story and offered the tapes and access in an effort to set the record straight.)

The narrative is clear and moves along briskly, even as it explores a great range of complex issues. Arnold and Jesse protest their innocence, Jesse louder than Arnold, David loudest of all as he stridently supports his father and viciously tears into his mother for expressing any doubts.

The reserved but blunt Elaine, isolated among the tight-knit males in her household, doesn't know what to believe as she learns that her 33-year marriage has been built on a foundation of lies. ("There was nothing between us but the children we yelled at," she says in retrospect.) We come to share her confusion.

The vivid accounts of computer-class assaults are undermined by an almost total lack of either physical evidence or previous complaints of abuse, leading one investigative journalist to inquire whether the entire case is built on community hysteria and the detectives' leading questions.

Jarecki allows his own interviews' wholly contradictory accounts to smack up against one another. One former student describing Arnold's basement sessions as nothing more than a boring computer class is followed by the lead investigator characterizing them as a "free-for-all." At first this lack of resolution is frustrating, like Jarecki owes it to us to solve this case in a way that investigators and journalists couldn't. But some facts may never be known, and others exist in such subjective places that they're beyond reconciliation.

One telling moment comes when David says he doesn't remember the night before Jesse's final court appearance except for what's on the family videotape. What he sees becomes his version of truth.

The same is true for this movie's viewers, who are sure to develop their own theories to make sense of the events. "Capturing the Friedmans" follows Arnold's and Jesse's cases through the court system and beyond (I won't give away what happens here), and we come to question our responses to just about everyone on screen. On the surface David comes across as the most unhinged of the Friedmans, while Arnold remains mild-mannered, Jesse relatively cool-headed.

"Capturing the Friedmans," which won the Grand Jury Prize at January's Sundance Film Festival, is a family drama that takes on an epic, Shakespearean scope. The more you learn, the more questions you have about life in that Great Neck house. Leo Tolstoy wrote that "every unhappy family is unhappy in its own fashion," but not even he could have invented the Friedmans.

SPELLBOUND

On its most basic level, Jeff Blitz's Spellbound (ThinkFilm) documents the 1999 nerd Olympics: 9 million nationwide spelling-bee contestants reduced to 249 finalists reduced to one winner. But the contest turns out to have a deeper resonance than if the sport had been merely physical: Among other things, mastery of the English language becomes a means of affirming one's American-ness. The movie is chiefly a portrait of eight aspiring contestants and their families. The first half introduces them singly in their hometowns: five girls and three boys from all over the country, from different races and economic classes—Angela, Nupur, Ted, Emily, Ashley, Neil, April, and wacky Harry. The second half is the bee itself, in Washington, D.C., where Blitz shows them knocked off, one by one, as in Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None—a favorite of the director's. But these kids aren't expendable drawing-room-mystery victims: It's devastating to watch their stabs of grief when they misspell obscure words (care for a hellebore, anyone?) and the bell goes ding! The movie becomes a nail-biter, the audience hanging on every letter. Who could have anticipated that a spelling competition would yield such a heartbreaking thriller?

You know that the director is onto something with the very first girl, Angela, whose father, Ubaldo, a ranch manager in Texas, speaks no English: The family crossed illegally into the United States from Mexico before she was born. Blitz doesn't sit the father down, the way he will the other parents, as if sensing that a straightforward interview would diminish the man. His uninsistent camera shows Ubaldo traipsing around the ranch, his domain, while his older son explains the risk his dad took so that his children would have an education. Fueled by little more than her parents' dreams, the gangly, giddy Angela is the best speller in her part of Texas—and the family will go to Washington for the first time in their lives.

You'll wonder how Blitz can top Angela, yet almost all these kids hook you on the same level. Nupur is the daughter of Indian immigrants—whose children, says her English teacher, have "a great work ethic." Then there's a cut to Nupur, sawing determinedly on her violin, serious beyond words. Blitz, who shot most of the movie himself on digital video, is a natural at framing these people in a way that captures their glorious individuality yet gives their lives a powerful social context. "You don't get second chances in India the way you do in America," says Nupur's father. And this is Nupur's second chance: The year before, she got knocked out of the nationals in the third round. This year, three local boys do their best to psych her out in the regional bee. But Nupur is unfazeable. The local Tampa, Fla. Hooters celebrates her regional win on its sign: "Congradu tions Nupur."

It's no wonder that the immigrant motif emerges so strongly in Spellbound: This melting-pot nation has a melting-pot language. English has roots in both German and Latin/French, with regular vocabulary infusions from sundry immigrant populations. Mastering its spelling requires both prodigious memorization and a grasp of each word's origins. Distress isn't limited to non-native speakers.

To select his subjects, Blitz and his co-producer, Sean Welch, reportedly combed lists of returning regional champions and picked the brains of countless officials and coaches. The order of the stories is significant, with the worldly, confident Nupur followed by Ted, a rural Missouri kid whose sense of isolation is palpable. "There are a couple of smart kids in my class but not many," he says—not sounding snotty, just lonely. Then it's on to the well-to-do Emily, who has a nice Connecticut home, an au pair, and a warmly supportive community; and Ashley, an African-American girl in southeast Washington, D.C., who has little community support or recognition. Ashley's mother sits smoking at her kitchen table, listing the obstacles her daughter has had to overcome, bitter over the lack of attention: The winner of the Washington metro bee, Ashley doesn't even have a trophy. But the girl herself—dressed in immaculate white—is radiant. "I'm a prayer warrior," she says. "I just can't stop praying. I rise above all my problems." Trying to convince herself as much as Blitz's camera, Ashley makes you want to cry.

In wealthy San Clemente, Calif., we don't see much of Neil—the focus is on his Indian father, whose children are vessels for his seemingly boundless ambition. He loves America: "If you work hard, you'll make it," he avers, and he has Neil working superhumanly hard, drilling him endlessly and hiring tutors in French, Spanish, and German to supplement his school's program in Latin. When we finally meet Neil, the kid seems barely conscious—diffident, almost robotic in his obedience. You know he'd rather be shooting hoops. Blitz follows the most high-pressure dad with a sweetly pessimistic one. In Ambler, Pa., cute, doleful April studies by herself from a battered unabridged dictionary while her father, owner of the rundown "Easy Street Pub," describes himself as "not a real success story," and her chipper mother says, "I can't even pronounce these words. It's rather sad." Surveying her own chances, April confesses, "I don't expect to get past the first round tomorrow." (Of course, I was rooting for April.) The final subject is New Jersey's irrepressible Harry—a twitchy, compulsively prattling uber-geek who tugs at the microphone ("Is this thing edible?") and nearly brings the national bee to a halt.

It's understandable that we root for the less privileged kids because they've made their own way in the world—but I wish that Blitz didn't show us Connecticut Emily trotting on a horse to reinforce the point that she has money. That said, Emily ultimately comes off as a nice girl with a healthy attitude. It's a measure of Blitz's humanism that even Neil's overbearing father has moments of grace. You can't hate him when you see him rocking in prayer for his son to succeed.

Spellbound is a gorgeous weave. When the contestants take the stage, the editor, Yana Gorskaya, cuts fluidly from the kids to their parents—often doubled over with anxiety—and back to the harrowing recitation of letters. Daniel Hulsizer's simple, plinking chords remind you of "Chopsticks" or a child's building blocks: It's the perfect music for this innocent—yet unnerving—milieu. The real-time tension is so strong that it's a relief when the movie takes a breather to meet contest officials and past spelling champions, among them the very first winner, from 1925. They remember their own sense of monklike isolation while they studied, the bond they felt to other social misfits when they arrived at the national finals, and their Olympian pride in victory.

Since seeing Spellbound, I've had many conversations with friends and colleagues about their spelling bee experiences. In the early '70s, I was in the last little group of spellers at my local Connecticut bee but got nailed—symbolically, it has been suggested—by the word "responsibility." My wife, only a decade before she'd embark on thousands of hours of therapy, flamed out on the word "psychiatrist." In Spellbound, Emily hates the word that knocked her out of the '98 bee and says that before it's all over, "I'm probably gonna hate one more word." The brother of a contestant who spells "distractible" with an "a" instead of an "i" insists, "I still think he spelled it right."

There is astonishing skill in Spellbound, but there are also accidents that seem blessed. It's almost like a novel when poor Ashley, the prayer warrior, freezes in terror on hearing the word "ecclesiastical," and when the Indian-American Neil, his head overstuffed with Latin, French, Spanish, and German, registers nothing but bewilderment when asked to spell "Darjeeling." The winner finishes with "logorrhea," which must be someone at the bee's idea of a grand joke. It sounds corny, but I had a hard time seeing any of these kids as losers—and a harder time figuring out how this deeply generous American documentary could have lost the Academy Award to Bowling for Columbine. Is it fair to ask whether most of the voters saw Spellbound? Or would that be irresponseble?

SWIMMING POOL

French director Francois Ozon doesn't like to repeat himself. His last film, 8 Women, was a theatrical, rather campy piece of fluff starring la crème de la crème of contemporary Gallic actresses. Before that came Under the Sand, an unsettling drama about a woman (Charlotte Rampling, giving perhaps her finest screen performance) who loses her grip on reality in the wake of her husband's disappearance. That film was preceded by Water Drops on Burning Rocks, a perverse psychosexual farce adapted from a play by the late German wunderkind Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Ozon's latest offering turns another 180 degrees. A delicious little thriller about an uptight, ill-humored English mystery writer who becomes enmeshed in murder, Swimming Pool is at once comical, contrary, resourceful and ambiguous. Only after it has ended does one realize that its salient characteristic is actually playfulness.

In her second collaboration with Ozon, Rampling stars as Sarah Morton, a British crime novelist whose repeated success has done nothing to improve her sour disposition. Bored with her own exceedingly popular literary creation, Sarah wants to stretch her artistic muscles, a desire discouraged by her editor and sometime lover John (Charles Dance), who is all too familiar with his client's prickly personality and demands for attention. John suggests that Sarah take a holiday and offers her the use of his home in the south of France. After initial grousing, she accepts.

It turns out to be just what the doctor ordered, a beautiful, quiet country home, peaceful and sunny, the perfect environment for Sarah's work. Her tranquility is almost immediately interrupted, however, by the unexpected arrival of John's teen-age French daughter Julie (another Ozon favorite, Ludivine Sagnier). The product of one of John's many extramarital liaisons, Julie is sexy, nonchalant and completely uninhibited. She lounges around the swimming pool topless and sleeps with a succession of unsuitable men. When her attempts to get along with Sarah are met with undisguised animosity, she stops trying.

Sarah's curiosity about Julie, however, grows. She takes to voyeuristically watching the young woman, going so far as to riffle through her diary. In an even more shocking lapse of ethics, Sarah pilfers passages from the diary for her new novel.

Giving away more of the plot would be unfair to the movie. While some of what transpires feels outlandish and even artificial, everything falls into place by the time the story draws to a close. And that's no mean feat.

Both actresses are superb. The normally sensual Rampling looks appropriately dour in unfashionable dresses and sensible shoes, but it is her clenched jaw, erect bearing and purposeful strides that so perfectly communicate her petulant nature and disdainful attitude toward her housemate. A scene in which she attacks a plate of profiteroles in a passive-aggressive rage is wonderful.

With her perfect breasts, pouty Lolita-esque posture and enviable lack of self-consciousness, Sagnier manages to convey a wide range of seemingly contradictory emotions and qualities: brashness, shyness, confidence, vulnerability, wanton sexuality, persuasive innocence. While Julie is supposed to be all of these things, it is difficult to think of another young actress who could suggest such conflicting traits so convincingly and in such a sympathetic manner.

Swimming Pool is Ozon's first English-language film (though a quarter of it is in French--subtitled, of course). Contributing greatly to the picture's overall effectiveness is Phillipe Rombi's Hitchcock-flavored score, a chilling little melody that crops up at infrequent intervals like signposts along a deserted highway, warning viewers of something off-kilter just beyond the bend.

CITY OF GOD

FIRST-TIME director Fernando Meirelles' "City of God" is like a bomb exploding in a fireworks factory: It's fierce and shocking and dazzling and wonderful. It opens with an absconding chicken, hot-footing it through a Rio de Janeiro slum, chased by a pack of gun-wielding teens firing off salvos with abandon. This place is called Cidade de Deus, or City of God - a misnomer if ever there was one, because it looks a lot like hell, and guns are as omnipresent as drugs.

The level of cruelty is bone-chilling, as seething hatreds fester and trigger-happy kids kill each other, but the sheer brilliance of Meirelles' filmmaking is in presenting the ultra-violence in a way that is neither heavy-handed nor blasé. Consider also the fact that Brazil's foremost director of commercials infuses his thoroughly engaging, character-heavy story with wicked humor and a truckload of style, and this debut marks him as one to watch. Screenwriter Braulio Mantovani has done a superb job adapting Paulo Lin's fact-based novel for the screen - no easy task, as Lin's book is an epic that spans three decades and features hundreds of characters.

The cast of mostly amateurs is exceptional, fully inhabiting the myriad characters who people this non-linear film, each one telling a different, interlocking story and each one unforgettable. Backtracking from that bravura opening scene to the 1960s - when the housing project was a moral vacuum, but not yet the diabolical gangland it would become - we meet two 11-year-old kids who will grow to take divergent paths: Rocket (Luis Otavio), a sensitive kid looking to escape the menace of the streets, and Lil Dice (Douglas Silva), a boy with a bloodlust that's shocking in its purity.

Cut to the '70s, and Lil Dice has become Lil Z (Leandro Firmino da Hora), the most feared drug dealer in the city, heading an army of killers as young as 9. When Lil Z gratuitously rapes the girlfriend of Knockout Ned (Seu Jorge), one of the few good guys in this wretched hellhole, Ned is bent on revenge. Ned goes over to the dark side, joining forces with Lil Z's rival drug dealer, Carrot (Matheus Nachtergaele), and, by the 1980s, the two warring gangs have begun tearing the city apart. Rocket (now played by Alexandre Rodrigues), meanwhile, has picked up a camera and has unparalleled access to no man's land. His pictures start landing on the front page of the newspaper.

Cinematographer Cesar Charlone illuminates the sun-drenched war zone with a golden hue and Meirelles' extraordinarily assured visual maneuvers (jump cuts, split screens, video capture, fast motion and scenes of carnage shot from on high, à la "Taxi Driver") make the frenzied action burn beneath a soundscape of funky samba rhythms and a blazing sun. "City of God," Brazil's official Oscar entry, is that rare film that manages to be seductively entertaining without ever compromising its authenticity and power.