MOVIES

Feux Rouges

The brilliant, sinister French thriller ''Red Lights,'' which opens today in New York, is a twisty road movie in which every sign points toward catastrophe. As night falls during the journey of Antoine (Jean-Pierre Darroussin), and Hélène (Carole Bouquet) Dunan, an unhappily married couple on their way from Paris to Bordeaux, the highway takes them into descending levels of psychosexual hell.

Antoine, a mousy, balding insurance salesman who suggests a dilapidated version of the 60's James Mason, hates his job, and whines out loud that he wants to ''live like a man'' and ''be free.'' He complains to Hélène, a sleek, far more successful corporate lawyer whose success galls him, that's she's too consumed with work. The Dunans are headed south to pick up their two children from summer camp. But even before they leave Paris, the tension between them hangs in the air like stale, sour static with nowhere to escape.

''Red Lights,'' adapted from a Georges Simenon novel set in America, sustains an appearance of realism even while embracing symbolic and surreal elements. Its eeriness is enhanced by its soundtrack's repetition of excerpts from Debussy's ''Nuages.'' Above all, it is a chilly study of an uncomfortably common breed of male paranoia. A major reason the marriage has turned rancid is that Antoine feels himself less than an equal partner. And with a sly, malicious humor, the film dramatizes his alcohol-fueled rebellion, which precipitates a grisly solution to his masculinity crisis.

The film was directed by Cédric Kahn, whose 1998 film, ''L'Ennui,'' immersed itself in a different kind of sexual paranoia. Based on a novel by Alberto Moravia, ''L'Ennui'' followed the descent into pathological obsession of an arrogant middle-aged philosopher who strikes up a casual affair with a woman barely out of adolescence toward whom he feels infinitely condescending. Sexually compliant but emotionally impenetrable, she slowly drives him mad with his desire to possess her out of pride that curdles into abject desperation.

Mr. Darroussin's depiction of Antoine as a glowering textbook example of passive-aggression is so uncompromising that Antoine often infuriates you. One way he vents his hostility toward Hélène is by secretly drinking during the trip. As you watch him tanking up at rest stops and stoking his resentment while she waits impatiently in the car, your sympathy for him ebbs, and you want to taunt him as a gutless, drunken milquetoast busily destroying himself. Yet the marriage is not lost. There are signs that a core of loyalty still exists between the two.

As Antoine finds himself stuck in crawling traffic, with episodes of gridlock, ''Red Lights'' reminds you of Godard's ''Weekend,'' and Claire Denis's ''Friday Night,'' movies in which traffic jams are disquieting metaphors for something bigger. Antoine quickly succumbs to road rage, which escalates the more he drinks. Against Hélène's wishes, he impulsively turns off the highway onto a darker route, and soon they are lost. Reports on the radio warn of an escaped convict from a prison in Le Mans and that roadblocks have been set up. The tension between the Dunans reaches the breaking point when Hélène warns her husband she's going to take the train. Stopping at another bar, he angrily takes the car keys with him.

Inside he is distracted by an English hippie who tells him he's driving in the wrong direction. When he returns, Hélène is gone. Driving like a maniac, he desperately tries to catch up with her train but misses each station by minutes.

In another, more ominous bar, he meets a mysterious, silent hitch-hiker (Vincent Deniard) whom he suspects may be the escaped convict, and offers him a lift. The implicit danger in which Antoine puts himself brings out a reckless bravado. Eventually they land inside a forest where Antoine endures a life-changing ordeal that becomes a Hemingway-esque rite of male passage.

The film captures the claustrophobic terror of an unstable driver and hostile passenger trapped in a speeding vehicle. It also conjures a primal dread of violence lurking in the night in strange territory. But its most suspenseful scene takes place the following morning in a diner. Shaken and hung over, Antoine desperately calls every railroad station and hospital in the area for news of his wife.

With a central character who at his most comically disoriented suggests Jacques Tati, ''Red Lights'' also owes much to Alfred Hitchcock's gallows humor. But it is completely its own movie. And the reverberations of its deceptively easygoing ending should set off debates among analysts of sexual power games in film for years to come.

The Return

The Russian film "The Return" is a stunning contemporary fable about a divided family in the wilderness - a simple, riveting film that almost achieves greatness.

In this hypnotic, stark movie, which won the Golden Lion (grand prize) of the last Venice Film Festival, we see a family strangely reunited: a father and his two sons traveling by car through the countryside after a 12-year separation. One of the boys, Andrei (the late Vladimir Garin), is obedient. The other younger son, Ivan (Ivan Dobronravov), is surly and rebellious.

The father himself (Konstantin Lavronenko) is an ex-pilot whose abandonment of his family is never explained. (Nor is his return.) Taciturn, muscular, glowering with the intimidating self-confidence of a career soldier, he dominates the boys and the landscape. As the three travel to a forest lake area on a fishing expedition, the tensions grow. Finally in the wilderness, on a ramshackle light tower that instills fear of falling in Ivan, they explode. "The Return" marks an amazing feature filmmaking debut by Andrei Zvyagintsev, a stage actor and TV director who also co-wrote the screenplay. Like many of the great Russian films, it has a mystical, poetic quality that invests the simplest scenes - walks through the forest, drives through the rain, the two boys fleeing through abandoned buildings - with power.

But the movie is also a potent psychological study. Told primarily from the viewpoint of young Ivan, it's a story of a child alienated from his long-absent father, bonded with his older brother, and how that child reacts when the father and discipline re-enter his life - and disrupt his bonds with mother and brother. Dobronravov, who bears a strong resemblance to the Haley Joel Osment of "The Sixth Sense," portrays Ivan with the perfect, self-contained egoism of childhood. Believing that everything revolves around him, he resents this strong, unknown intruder - even doubting that he's a pilot or really their father.

In a film by Tarkovsky as much as a novel by Dostoyevsky, something always seethes below the surface. And there always seems to be more here than we see or the characters can say. "The Return" might be seen as a symbolic study of a nation adjusted to loss of a tyrannical superstructure, suddenly coping with its return.

Perhaps that's not what Zvyagintsev intends. But one feels throughout this taut film, with its gray landscapes (beautifully photographed by Mikhail Krichman) and its air of mounting doom - right up to its shocking climax - that every event and every speech has significance beyond what we see, even though the film itself isn't didactic or preachy.

"The Return" has a power almost biblical in its purity. Like the tale of Abraham and Isaac, this story invests family conflict and tragedy with cosmic inevitability and force.

Closer

Mike Nichols' "Closer" is a movie about four people who richly deserve one another. Fascinated by the game of love, seduced by seduction itself, they play at sincere, truthful relationships which are lies in almost every respect, except their desire to sleep with each other. All four are smart and ferociously articulate, adept at seeming forthright and sincere even in their most shameless deceptions.

"The truth," one says. "Without it, we're animals." Actually, truth causes them more trouble than it saves, because they seem compelled to be most truthful about the ways in which they have been untruthful. There is a difference between confessing you've cheated because you feel guilt and seek forgiveness, and confessing merely to cause pain.

The movie stars, in order of appearance, Jude Law, Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts and Clive Owen. Law plays Dan, who writes obituaries for his London newspaper; Portman is Alice, an American who says she was a stripper and fled New York to end a relationship; Roberts is Anna, an American photographer; and Owen is Larry, a dermatologist. The characters connect in a series of Meet Cutes that are perhaps no more contrived than in real life. In the opening sequence, the eyes of Alice and Dan (Natalie Portman and Jude Law) meet as they approach each other on a London street. Eye contact leads to an amused flirtation, and then Alice, distracted, steps into the path of a taxicab. Knocked on her back, she opens her eyes, sees Dan, and says "Hello, stranger." Time passes. Dan writes a novel based on his relationship with Alice, and has his book jacket photo taken by Anna, who he immediately desires. More time passes. Dan, who has been with Anna, impersonates a woman named "Anna" on a chat line, and sets up a date with Larry, a stranger. When Larry turns up as planned at the aquarium, Anna is there, but when he describes "their" chat, she disillusions him: "I think you were talking with Daniel Wolf."

Eventually both men will have sex with both women, occasionally as a round trip back to the woman they started with. There is no constancy in this crowd: When they're not with the one they love, they love the one they're with. It is a good question, actually, whether any of them are ever in love at all, although they do a good job of saying they are.

They are all so very articulate, which is refreshing in a time when literate and evocative speech has been devalued in the movies. Their words are by Patrick Marber, based on his award-winning play. Consider Dan as he explains to Alice his job writing obituaries. There is a kind of shorthand, he tells her: "If you say someone was

'convivial,' that means he was an alcoholic. 'He was a private person’

means he was gay. 'Enjoyed his privacy' means he was a raging queen."

Forced to rank the four characters in order of their nastiness, I would place Dr. Larry at the top of the list. He seems to derive genuine enjoyment from the verbal lacerations he administers, pointing out the hypocrisies and evasions of the others.

Dan is an innocent by comparison; he wants to be bad, but isn't good at it. Anna, the photographer, is accurately sniffed out by Alice as a possible lover of Dan. "I'm not a thief, Alice," she says, but she is. Alice seems the most innocent and blameless of the four until the very end of the movie, when we are forced to ask if everything she did was a form of stripping, in which much is revealed, but little is surrendered. "Lying is the most fun a girl can have without taking her clothes off," she tells Dr. Larry, "but it's more fun if you do."

There's a creepy fascination in the way these four characters stage their affairs while occupying impeccable lifestyles. They dress and present themselves handsomely. They fit right in at the opening of Anna's photography exhibition. (One of the photographs shows Alice with tears on her face as she discerns that Dan was unfaithful with Anna; that's the stuff that art is made of, isn't it?) They move in that London tourists never quite see, the London of trendy restaurants on dodgy streets, and flats that are a compromise between affluence and the exorbitant price of housing. There is the sense that their trusts and betrayals are not fundamentally important to them; "You've ruined my life," one says, and then is told, "You'll get over it."

Yes, unless, fatally, true love does strike at just that point when all the lies have made it impossible. Is there anything more pathetic than a lover who realizes he (or she) really is in love, after all the trust has been lost, all the bridges burnt and all the reconciliations used up?

Mike Nichols has been through the gender wars before, in films like "Carnal Knowledge" and "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf." Those films, especially "Woolf," were about people who knew and understood each other with a fearsome intimacy and knew all the right buttons to push.

What is unique about "Closer," making it seem right for these insincere times, is that the characters do not understand each other, or themselves. They know how to go through the motions of pushing the right buttons, and how to pretend their buttons have been pushed, but do they truly experience anything at all except their own pleasure?

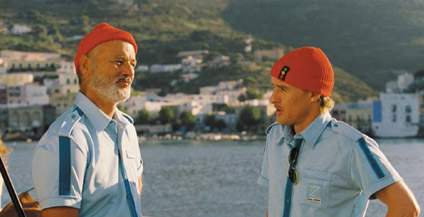

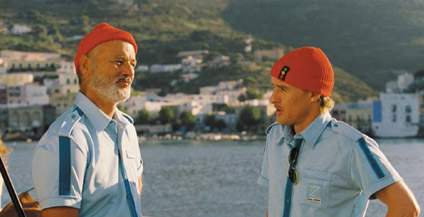

The Life Aquatic

Although still fond of oddballs and eccentrics, Wes Anderson moves past the merely quirky in "The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou," his wonderfully weird and wistful adventure-comedy about a fish-out-of-water oceanographer. Following his Oscar-nominated turn in "Lost in Translation," Bill Murray brings his singularly edgy ennui to the unlikely role of a modern-day Ahab.

The writer-director's most recent film, "The Royal Tenenbaums," was a museum collection of character types that never coalesced into an affecting story. Here, sharing scripting duties with Noah Baumbach, Anderson still struggles to fuse character observation with feeling, and most of the proceedings unfold at an emotional distance. But, in the helmer's most expansive project yet, the cast's commitment and the inventive milieu, rendered with enormous care, keep the story well afloat. Given Murray's heightened boxoffice profile and Anderson's loyal following, "Aquatic," which goes wide Christmas Day after its New York/L.A. bow Friday, should reel in high midrange receipts.

Steve Zissou (Murray) is a 52-year-old American version of Jacques Cousteau but without the joie de vivre. He moves with a weary stiffness, and when a child presents him with a brightly striped seahorse -- the first of the film's many fantastic creatures -- he glances impassively at it. Later, he flicks a Day-Glo yellow lizard off his wrist with cavalier spite.

Steve's empire of all things Zissou has been in decline for a decade, and he's having trouble securing financing for Part 2 of his latest documentary. The object is revenge: He intends to hunt down the mysterious jaguar shark that devoured his lead diver and best friend (Seymour Cassel) before his eyes in Part 1.

As in "Tenenbaums," Anderson's focus is a reluctant father figure, and a familial story soon supplants the obsessive Moby-Dick angle. Just before the Belafonte, Zissou's converted World War II submarine hunter, heads out to sea, a young man named Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson), genteel to the point of quaintness, introduces himself as Steve's possible son from a long-ago liaison. Responding to the admiration in Ned's eyes -- and sensing a "relationship subplot" for the documentary -- Steve invites him to join Team Zissou's expedition. Ned proves smarter than his mellow exterior would suggest, and soon he's bailing out the strapped production and provoking the jealousy of devoted engineer Klaus (Willem Dafoe, delivering a comic and touching performance).

Also on board is an at-loose-ends pregnant British journalist (a disappointingly wan Cate Blanchett) and the bond company rep, a milquetoast who turns out to be a mensch (Bud Cort, terrific). Staying behind is Steve's wife, Eleanor (a regal Anjelica Huston), who objects to the mission. Although their marriage is running on fumes, it's a blow to Steve; she's the brains of the operation. Twisting the knife, she opts for R&R at the tropical estate of her ex, Hennessey (Jeff Goldblum, an effective nemesis), a glamour-boy oceanographer whose state-of-the-art sea lab casts Zissou in the dated shadows.

Highlighting the story's melancholy are musical interludes by actor-musician Seu Jorge ("City of God"), playing a guitar-strumming member of the crew who sings David Bowie songs in Portuguese. "Ziggy Stardust" in the language of fado is a strange and beautiful thing, encapsulating the dislocation, sadness and wonder that define the film's watery world.

Anderson's deep affection for his "pack of strays" is clear, and the final moments of the film are truly moving. But much of the time the characters' specific emotions play out at a remove, filtered through ironic humor and high-seas danger. Murray convincingly conveys an existential ache, but Steve's paternal pangs lack the intended impact, and -- Wilson's fine performance notwithstanding -- Ned is more device than character.

Eschewing digital effects for hand-crafted whimsy, the film uses stop-motion animation by Henry Selick ("The Nightmare Before Christmas") for such delightful creations as candy-colored sugar crabs and rhinestone bluefins. Robert Yeoman's fluid camerawork captures the expressive production design of Mark Friedberg, especially the Belafonte's faded glory. The handsome, Italy-shot production also benefits from Milena Canonero's slightly cartoony, character-defining costumes and Mark Mothersbaugh's jaunty score.

The Aviator

The Aviator

An enormously entertaining slice of biographical drama, "The Aviator" flies like one of Howard Hughes' record-setting speed airplanes. While it doesn't dig deeply into the psychology of one of the most famous industrialists and behavioral oddballs of the 20th century, Martin Scorsese's most pleasurable narrative feature in many a year is both extravagant and disciplined, grandly conceived and packed with minutiae. Although he was not exactly born for the role, Leonardo DiCaprio is in terrific movie star mode portraying an often inscrutable man whose passion for planes, motion pictures and beautiful women is emphatically expressed. The director/star combo assures considerable public interest, but the film's commercial fate hangs on two big ifs -- the domestic Miramax release building momentum as a major awards contender into the new year and the lavish period piece capturing the interest of younger auds.

Concentrating on the key years of the young Hughes' greatest accomplishments, from his splash in late-'20s Hollywood with his World War I epic "Hell's Angels" to setting flying records in the '30s and taking on the U.S. government and aviation giant Pan Am in the '40s, screenwriter John Logan made difficult choices about what to dwell upon and what to sweep over in montage-like fashion. He has done so intelligently, with preference for his subject's maniacal industriousness but with enough private moments to provide touchstones for his increasingly eccentric traits.

Scorsese, who came aboard the project when Michael Mann decided he couldn't do a third big bio picture in a row, has injected his own mania for cinema into Hughes' obsession for aviation and, secondarily, for filmmaking and actresses. Resulting energy propels every aspect of the production, notably the performances, exceptionally dense soundtrack and magnificent design. If "Gangs of New York" felt heavy and never found its proper rhythm, "The Aviator" runs like a dream on all cylinders with scarcely a sputter or a cough.

After an odd opening in which Hughes' mother gives her young son an overly attentive bath during a flu quarantine, action jumps to 1927 Hollywood, when the 21-year-old Hughes, already wealthy from the family oil well drill bits business, sank millions into "Hell's Angels." Hughes, learning to direct on the job at his own expense, was forced to remake most of his silent picture when sound came in, driving the production schedule to three years.

Scorsese's action-painting evocation of the laborious shoot is exhilarating and amusing, combining footage from the actual picture with shots of dozens of biplanes diving in dizzying patterns, often with Hughes himself up in the air with a camera. At one point, the director halts production until Mother Nature can provide the background he wants -- clouds that resemble giant breasts.

Although Louis B. Mayer is seen being dismissive of the brash upstart at the Cocoanut Grove (just one of many locations lovingly recreated by production designer Dante Ferretti), film underplays the extent to which the outsider was shunned by the studio heads. Their hostility pushed Hughes into an increasingly adversarial stance toward Hollywood, a position that foreshadowed his later contentious relationships with the aviation industry and Washington.

Hughes breaths a sigh of relief after the successful premiere of "Hell's Angels" at Grauman's Chinese, an event stunningly rendered via staged material and colorized vintage newsreel footage; with Hollywood Boulevard festooned with large model planes dangling overhead, preem drew a reported 500,000 people and served as the inspiration for Nathaniel West's "The Day of the Locust."

As the action jumps to the mid-'30s, Hughes lands a plane at the beach location of "Sylvia Scarlett" to fetch Katharine Hepburn (Cate Blanchett) for a round of golf. This cockeyed romance, which lasts considerably longer in the film than it did in real life, proves as charming as it is unlikely, thanks in large measure to Blanchett's dead-on rendering of the star's hauteur and vocal peculiarities.

Once the startling impact of her impersonation has subsided, the relationship successfully defines itself as a pairing of two completely self-absorbed misfits. The bond is strengthened by the rarefied air they share as two of the most famous people in the world, romanticized in a lovely "date" on Hughes' plane over Los Angeles at night and unsettled in a brilliantly funny sequence in which Hepburn takes her beau to the family compound in Connecticut, where the eccentric clan's air of self-obsessed superiority makes the famous daughter look like a piker (Frances Conroy's cameo as Mrs. Hepburn is indelible).

Although he continued to dabble in pictures, aviation consumed Hughes far more. Pic raptly documents his creation of the H-1 Racer, a sleek silver bullet in which he set the world speed record; his record-setting 1936 'round-the-world flight (partly conveyed by doc footage in which DiCaprio's face has been laid, "Zelig"-like, over the real thing); his 1946 test flight of the XF-11, which concluded with its pilot's nearly fatal crash into several houses in Beverly Hills, a spectacle rendered here with incredible force and detail; his support for the swan-like Constellation passenger plane, which made his TWA into a world-class airline, and his contentious construction of the world's biggest flying machine, the Hercules, or Spruce Goose, the one and only flight of which provides the picture with its stirring climax.

Since planes represent one of the great subjects for motion picture cameras, enthusiasts will have a field day watching all these amazing aircraft onscreen, both in live-action and in eminently satisfying CGI representations. It's not that you can't tell when a flight is being digitally rendered, but it's all done amazingly well -- the degree of artifice surrounding the entire picture allows the computer work to fit in gracefully rather than to stick out.

Said artifice is established by a visual style devised by Scorsese and cinematographer Robert Richardson that emphasizes the primary colors dominant in the Technicolor images of '30s and '40s Hollywood, albeit with subtle gradations that shift according to the era.

While "The Aviator" is not remotely intended to look or feel like a classical studio picture -- there's far too much movement and razzle-dazzle -- Scorsese artfully uses all the latest techniques in the service of evoking the periods in question. In every respect, the film is a technological marvel.

Dramatically, story crescendos with the rivalry between Hughes and Pan Am's Juan Trippe (a very effective Alec Baldwin), whose monopoly on international air travel by a U.S. company Hughes means to break with his TWA Constellations. Trippe (whose office in the upper realms of the Chrysler Building is a wonder to behold) acquires a powerful crony in Sen. Ralph Owen Brewster (Alan Alda, superb), who intends to crush Hughes in Senate hearings pinned to the tycoon's alleged squandering of government money on failed airplane projects.

Rooted, according to the script's logic, in his mother's protective preoccupation, Hughes exhibits an increasing phobia about germs, expressed in ever-more bizarre behavior in public restrooms, as well as insecurity about his deafness and mental stability. He comes temporarily unhinged after his 1946 plane crash, locking himself in his screening room and growing a beard, long hair and nails while sexy images of Jane Russell flicker on the screen, all intimating the bizarre accounts of his reclusive later life.

The huge number of women Hughes collected over the years can only be glancingly noted.

Of them, just two beyond Hepburn are even shown, Faith Domergue (Kelli Garner), a hapless teenager Hughes groomed for never-to-be stardom, and, more prominently, Ava Gardner (Kate Beckinsale). Although the latter pops up, mostly argumentatively, several times, the nature of her relationship with Hughes remains unclear (by her own testimony, they never slept together), giving their scenes fuzzy import.

Physically, DiCaprio is not as tall, rangy or rugged as the real Hughes, and the remnants of his baby face are at utter odds with the angles and creases of Hughes' mug. But the actor completely engages with the role in all the ways that count, conveying utter absorption in his work, driving perfectionism, masculine allure, public reticence, increasing eccentricity and simmering hostility for anything that stands in his way.

One can still imagine that Warren Beatty would once have been the ideal bigscreen Hughes, and regret that Beatty never managed to make what should have been his great romance of capitalism to match his epic romance of communism, "Reds." But DiCaprio puts his imprint on the part with surprising effectiveness.

Aside from members of Hughes' inner circle played with intentional modesty by John C. Reilly, Ian Holm, Matt Ross and Adam Scott, other characters sweep in and out like gusts of wind: Among them are Errol Flynn (a vivaciously insouciant Jude Law), Jean Harlow (Gwen Stefani with a couple of lines), MPAA censorship czar Joseph Breen (a harrumphing Edward Herrmann) and a sleazy magazine publisher (Willem Dafoe).

Ever-present music plays a key role in sustaining the film's effervescence, as Howard Shore's propulsive original score meshes seamlessly with an enormous assortment of popular tunes from the periods played boisterously in nightclub settings or subtly in the background.

Maria Full of Grace

Maria Full of Grace

Long-stemmed roses must come from somewhere, but I never gave the matter much thought until I saw "Maria Full of Grace," which opens with Maria working an assembly line in Colombia, preparing the roses for shipment overseas. I guess I thought the florist picked them early every morning, while mockingbirds trilled. Maria is young and pretty and filled with fire, and when she finds she's pregnant, she isn't much impressed by the attitude of Juan, her loser boyfriend. She dumps her job and gets a ride to Bogota with a man who tells her she could make some nice money as a mule -- a courier flying to New York with dozens of little Baggies of cocaine in her stomach.

Maria (Catalina Sandino Moreno) is being exploited by the drug business, but she sees it as an opportunity. Her best friend Blanca (Yenny Paola Vega) comes along, and they get tips from Lucy (Giulied Lopez), who has been a mule before; it's a way to visit her sister in New York.

At Kennedy Airport, the customs officials weren't born yesterday and consider the girls obvious suspects, but Maria can't be X-rayed because she's pregnant. The girls slip through and make contact with two witless drug workers whose job is to guard them while the drug packets emerge. But Lucy is feeling ill. A packet has broken in her stomach, and soon she's dead of an overdose. Her body is crudely disposed of by the two workers; her death is nothing more than a cost of doing business.

Maria is a victim of economic pressures, but she doesn't think like a victim. She has spunk and intelligence and can think on her feet, and the movie wisely avoids the usual cliches about the drug cartel and instead shows us a fairly shabby importing operation, run by people more slack-jawed than evil. Here is a drug movie with no machineguns and no chases. It focuses on its human story, and in Catalina Sandino Moreno, finds a bright-eyed, charismatic actress who engages our sympathy.

The story of the making of the movie is remarkable. It was filmed on an indie budget by Joshua Marston, a first-time American director in his 30s, who found Moreno at an audition, cast mostly unknowns, and used real people in some roles -- notably Orlando Tobin, who in life as in the film operates out of a Queens storefront, acting as middleman and counselor to Colombian immigrants in need.

The movie has the freshness and urgency of life actually happening. There's little feeling that a plot is grinding away; instead, Maria takes this world as she finds it and uses common sense to try to survive. She makes one crucial decision that a lesser movie would have overlooked; she goes to find the sister who Lucy came to visit.

I learn from Ella Taylor's article in the L.A. Weekly that one of Marston's favorite directors is Ken Loach, the British poet of working people. Like Loach, Marston has made a film that understands and accepts poverty without feeling the need to romanticize or exaggerate it. Also like Loach, he shows us how evil things happen because of economic systems, not because villains gnash their teeth and hog the screen. Hollywood simplifies the world for moviegoers by pretending evil is generated by individuals, not institutions; kill the bad guy, and the problem is solved.

"Maria Full of Grace" is an extraordinary experience for many reasons, including, oddly, its willingness to be ordinary. We see everyday life here, plausible motives, convincing decisions, and characters who live at ground level. The movie's suspense is heightened by being generated entirely at the speed of life, by emerging out of what we feel probably would really happen. Consider the way the two drug middlemen are seen as depraved and cruel, but also as completely banal, as bored by their job as Maria was with the roses. Most drug movies are about glamorous stars surrounded by special effects. Meanwhile, in a world almost below the radar, the Marias and Lucys hopefully board their flights with stomachs full of death.

The Son

The Son" is complete, self-contained and final. All the critic can bring to it is his admiration. It needs no insight or explanation. It sees everything and explains all. It is as assured and flawless a telling of sadness and joy as I have ever seen.

I agree with Stanley Kauffmann in The New Republic, that a second viewing only underlines the film's greatness, but I would not want to have missed my first viewing, so I will write carefully. The directors, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, do not make the slightest effort to mislead or deceive us. Nor do they make any effort to explain. They simply (not so simply) show, and we lean forward, hushed, reading the faces, watching the actions, intent on sharing the feelings of the characters.

Let me describe a very early sequence in enough detail for you to appreciate how the brothers work. Olivier (Olivier Gourmet), a Belgian carpenter, supervises a shop where teenage boys work. He corrects a boy using a power saw. We wonder, because we have been beaten down by formula films, if someone is going to lose a finger or a hand. No. The plank is going to be cut correctly.

A woman comes into the shop and asks Olivier if he can take another apprentice. No, he has too many already. He suggests the welding shop. The moment the woman and the young applicant leave, Olivier slips from the shop and, astonishingly, scurries after them like a feral animal and spies on them through a door opening and the angle of a corridor. A little later, strong and agile, he leaps up onto a metal cabinet to steal a look through a high window.

Then he tells the woman he will take the boy after all. She says the boy is in the shower room. The hand-held camera, which follows Olivier everywhere, usually in close medium shot, follows him as he looks around a corner (we intuit it is a corner; two walls form an apparent join). Is he watching the boy take a shower? Is Olivier gay? No. We have seen too many movies. He is simply looking at the boy asleep, fully clothed, on the floor of the shower room. After a long, absorbed look, he wakes up the boy and tells him he has a job.

Now you must absolutely stop reading and go see the film. Walk out of the house today, tonight, and see it, if you are open to simplicity, depth, maturity, silence, in a film that sounds in the echo-chambers of the heart. "The Son" is a great film. If you find you cannot respond to it, that is the degree to which you have room to grow. I am not being arrogant; I grew during this film. It taught me things about the cinema I did not know.

What did I learn? How this movie is only possible because of the way it was made, and would have been impossible with traditional narrative styles. Like rigorous documentarians, the Dardenne brothers follow Olivier, learning everything they know about him by watching him. They do not point, underline or send signals by music. There are no reaction shots because the entire movie is their reaction shot. The brothers make the consciousness of the Olivier character into the auteur of the film.

... So now you have seen the film. If you were spellbound, moved by its terror and love, struck that the visual style is the only possible one for this story, then let us agree that rarely has a film told us less and told us all, both at once.

Olivier trains wards of the Belgian state--gives them a craft after they are released from a juvenile home. Francis (Morgan Marinne) was in such a home from his 11th to 16th years. Olivier asks him what his crime was. He stole a car radio.

"And got five years?" "There was a death." "What kind of a death?" There was a child in the car who Francis did not see. The child began to cry and would not let go of Francis, who was frightened and "grabbed him by the throat." "Strangled him," Olivier corrects.

"I didn't mean to," Francis says.

"Do you regret what you did?" "Obviously." "Why obviously?" "Five years locked up. That's worth regretting." You have seen the film and know what Olivier knows about this death. You have seen it and know the man and boy are at a remote lumber yard on a Sunday. You have seen it and know how hard the noises are in the movie, the heavy planks banging down one upon another. How it hurts even to hear them. The film does not use these sounds or the towers of lumber to create suspense or anything else. It simply respects the nature of lumber, as Olivier does and is teaching Francis to do. You expect, because you have been trained by formula films, an accident or an act of violence. What you could not expect is the breathtaking spiritual beauty of the ending of the film, which is nevertheless no less banal than everything that has gone before.

Olivier Gourmet won the award for best actor at Cannes 2002. He plays an ordinary man behaving at all times in an ordinary way. Here is the key: o rdinary for him. The word for his behavior--not his performance, his behavior--is "exemplary." We use the word to mean "praiseworthy." Its first meaning is "fit for imitation." Everything that Olivier does is exemplary. Walk like this. Hold yourself just so. Measure exactly. Do not use the steel hammer when the wooden mallet is required. Center the nail. Smooth first with the file, then with the sandpaper. Balance the plank and lean into the ladder. Pay for your own apple turnover. Hold a woman who needs to be calmed. Praise a woman who has found she is pregnant. Find out the truth before you tell the truth. Do not use words to discuss what cannot be explained. Be willing to say, "I don't know." Be willing to have a son and teach him a trade. Be willing to be a father.

A recent movie got a laugh by saying there is a rule in "The Godfather" to cover every situation. There can never be that many rules. "The Son" is about a man who needs no rules because he respects his trade and knows his tools. His trade is life. His tools are his loss and his hope.