12.20.2005

12.12.2005

MUSIC

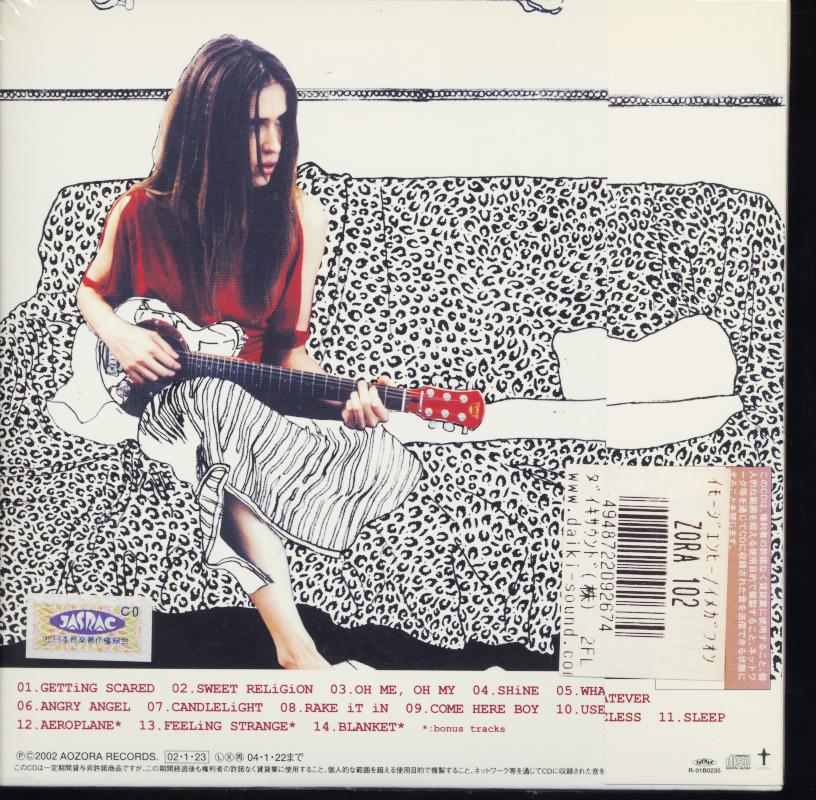

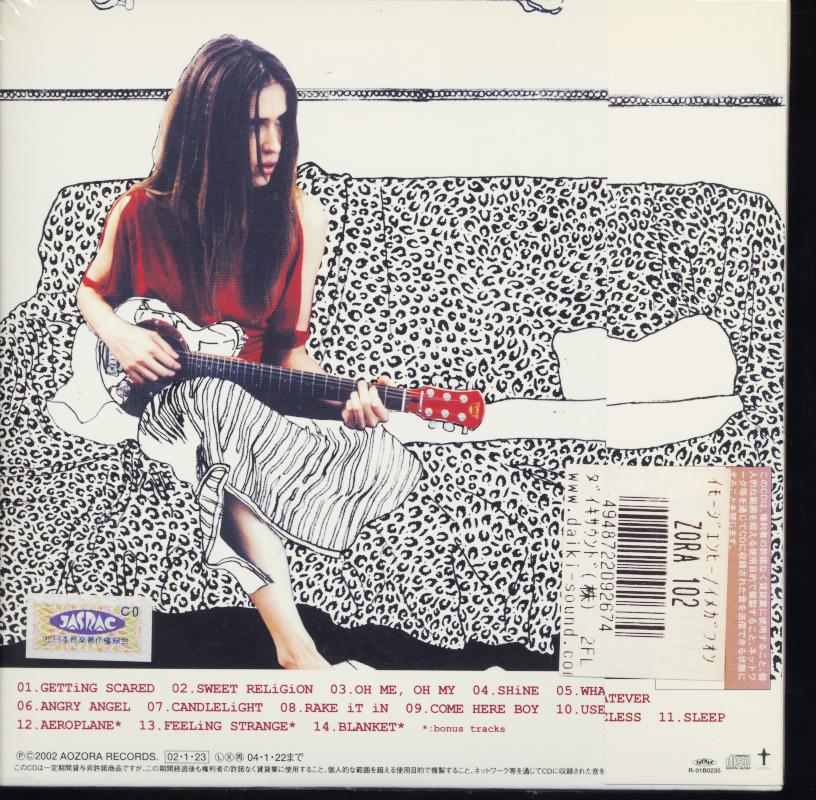

Beck

Beck's eyes are preternaturally blue, and until recently, exactly what lay behind them was something of an enigma. Whether clowning in videos, spontaneously breakdancing at awards shows, or just gazing ahead on his album covers, the junkyard boho was always looking beyond, seemingly into a bizarre realm unhindered by genre-- or behavioral-- expectations. But lately, he just looks lost. Wandering down a gimmicky path lined with empty pop-up confections in the "Girl" video, the 35-year-old dad with bad hair found himself relegated to the role of passerby. More than ever, 2005 saw Beck losing his edge. So, on this take two, he embraces the talent and ideas of contemporaries and descendants alike (all of whom, I'm sure, are really, really nice), hoping for a little friendly friction. Much like its inconsistent source material, Guerolito emits a few flashes but lacks the cohesiveness that was once this innovator's hallmark.

Possibly a sign of self-conscious second-guessing, Beck began to commission new mixes for Guero early on. Oddly, the lo-fi blip GameBoy Variations EP, featuring remixes for four of the album's songs, was thrown up online a full two months before Guero's official release. Then, over the course of the year, about a half-dozen more trickled out. Wisely, not all of these previously released alternates-- including lazy efforts from Dizzee Rascal and Röyksopp-- are included here. All in all, nine of Guerolito's 14 tracks are new, which, along with fresh artwork courtesy of surrealist Guero cover illustrator Marcel Dzama, and a track-for-track sequencing, indicates the intention of a true remix album rather than just another careless fourth-quarter hodge-podge ch-ching. While such efforts are duly noted, the bare-bones liners and widely varying quality of these retries make Guerolito better suited for iTunes cherry-picking than full-on Amazon consumption.

Several tracks equal or trump their initial incarnations by emphasizing pluses and playing into their remixers' entrenched strengths. Both Boards of Canada and Air are wonderfully type-cast; the former's take on "Broken Drum" highlights Beck's Sea Change-y lonesome vocals with apropos amble ambience while the latter's "Missing" redux, "Heaven Hammer", boosts sexy-church synths, echoing drums, and everything else you'd expect from France's finest purveyors of cheesy-cool. The new "Scarecrow", courtesy of El-P, is a marked improvement on its predecessor, with the hip-hop producer's succinct drums and keyboard stabs giving the song a newfound strut. Meanwhile, golden boy Diplo reiterates his current crate-king status by slowing down the staccato bass backbone of the English Beat's "Twist and Crawl" to provide his "Go It Alone" redo with a stealth funk.

Alas, many other attempts fall flat due to weak, repetitive arrangements, or an inability to convincingly congeal with their forebears. The worst offender is nerd rap group Subtle, whose lumbering "Farewell Ride" won't entice anybody to grab onto the Anticon trolley anytime soon. (I hope.) Two ex-Unicorn projects are represented, and neither clicks, though for different reasons; Islands' Uni-lite twee instrumentation sounds woefully out of place when meshed with Beck's East L.A. non-sequiturs on "Que Onda Guero" (not to mention the ill-fated, half-assed screwed 'n' chopped bit), while Th' Corn Gangg's electro R2-D2 spin on "Emergency Exit" takes too long to climax with its dense thump and cut-up vox. And just when you thought the Beasties couldn't get more annoying, Adrock comes along with his throwback minimalist-clang take on "Black Tambourine" featuring enough repeating "ugh!" and "what!" drops to make you want to steamroll your copy of Check Your Head.

His fierce glint fading, it's becoming increasingly clear that Beck is no longer able to freely revel in the youthful dalliances that made him famous more than a decade ago. Guerlito's standouts prove that proper taste and a good ear can be just as valuable as songwriting to a multi-tasker like Beck, but even for an artist this venerable, a remix record is still a remix record-- generally uneven, part enlightening, and part skippable.

TURKEY

ON TRIAL

by Orhan Pamuk

New Yorker

In Istanbul this Friday—in SiSli, the district where I have spent my whole life, in the courthouse directly opposite the three-story house where my grandmother lived alone for forty years—I will stand before a judge. My crime is to have “publicly denigrated Turkish identity.” The prosecutor will ask that I be imprisoned for three years. I should perhaps find it worrying that the Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink was tried in the same court for the same offense, under Article 301 of the same statute, and was found guilty, but I remain optimistic. For, like my lawyer, I believe that the case against me is thin; I do not think I will end up in jail.

This makes it somewhat embarrassing to see my trial overdramatized. I am only too aware that most of the Istanbul friends from whom I have sought advice have at some point undergone much harsher interrogation and lost many years to court cases and prison sentences just because of a book, just because of something they had written. Living as I do in a country that honors its pashas, saints, and policemen at every opportunity but refuses to honor its writers until they have spent years in courts and in prisons, I cannot say I was surprised to be put on trial. I understand why friends smile and say that I am at last “a real Turkish writer.” But when I uttered the words that landed me in trouble I was not seeking that kind of honor.

Last February, in an interview published in a Swiss newspaper, I said that “a million Armenians and thirty thousand Kurds had been killed in Turkey”; I went on to complain that it was taboo to discuss these matters in my country. Among the world’s serious historians, it is common knowledge that a large number of Ottoman Armenians were deported, allegedly for siding against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, and many of them were slaughtered along the way. Turkey’s spokesmen, most of whom are diplomats, continue to maintain that the death toll was much lower, that the slaughter does not count as a genocide because it was not systematic, and that in the course of the war Armenians killed many Muslims, too. This past September, however, despite opposition from the state, three highly respected Istanbul universities joined forces to hold an academic conference of scholars open to views not tolerated by the official Turkish line. Since then, for the first time in ninety years, there has been public discussion of the subject—this despite the spectre of Article 301.

If the state is prepared to go to such lengths to keep the Turkish people from knowing what happened to the Ottoman Armenians, that qualifies as a taboo. And my words caused a furor worthy of a taboo: various newspapers launched hate campaigns against me, with some right-wing (but not necessarily Islamist) columnists going as far as to say that I should be “silenced” for good; groups of nationalist extremists organized meetings and demonstrations to protest my treachery; there were public burnings of my books. Like Ka, the hero of my novel “Snow,” I discovered how it felt to have to leave one’s beloved city for a time on account of one’s political views. Because I did not want to add to the controversy, and did not want even to hear about it, I at first kept quiet, drenched in a strange sort of shame, hiding from the public, and even from my own words. Then a provincial governor ordered a burning of my books, and, following my return to Istanbul, the ?i?li public prosecutor opened the case against me, and I found myself the object of international concern.

My detractors were not motivated just by personal animosity, nor were they expressing hostility to me alone; I already knew that my case was a matter worthy of discussion in both Turkey and the outside world. This was partly because I believed that what stained a country’s “honor” was not the discussion of the black spots in its history but the impossibility of any discussion at all. But it was also because I believed that in today’s Turkey the prohibition against discussing the Ottoman Armenians was a prohibition against freedom of expression, and that the two matters were inextricably linked. Comforted as I was by the interest in my predicament and by the generous gestures of support, there were also times when I felt uneasy about finding myself caught between my country and the rest of the world.

The hardest thing was to explain why a country officially committed to entry in the European Union would wish to imprison an author whose books were well known in Europe, and why it felt compelled to play out this drama (as Conrad might have said) “under Western eyes.” This paradox cannot be explained away as simple ignorance, jealousy, or intolerance, and it is not the only paradox. What am I to make of a country that insists that the Turks, unlike their Western neighbors, are a compassionate people, incapable of genocide, while nationalist political groups are pelting me with death threats? What is the logic behind a state that complains that its enemies spread false reports about the Ottoman legacy all over the globe while it prosecutes and imprisons one writer after another, thus propagating the image of the Terrible Turk worldwide? When I think of the professor whom the state asked to give his ideas on Turkey’s minorities, and who, having produced a report that failed to please, was prosecuted, or the news that between the time I began this essay and embarked on the sentence you are now reading five more writers and journalists were charged under Article 301, I imagine that Flaubert and Nerval, the two godfathers of Orientalism, would call these incidents bizarreries, and rightly so.

That said, the drama we see unfolding is not, I think, a grotesque and inscrutable drama peculiar to Turkey; rather, it is an expression of a new global phenomenon that we are only just coming to acknowledge and that we must now begin, however slowly, to address. In recent years, we have witnessed the astounding economic rise of India and China, and in both these countries we have also seen the rapid expansion of the middle class, though I do not think we shall truly understand the people who have been part of this transformation until we have seen their private lives reflected in novels. Whatever you call these new élites—the non-Western bourgeoisie or the enriched bureaucracy—they, like the Westernizing élites in my own country, feel compelled to follow two separate and seemingly incompatible lines of action in order to legitimatize their newly acquired wealth and power. First, they must justify the rapid rise in their fortunes by assuming the idiom and the attitudes of the West; having created a demand for such knowledge, they then take it upon themselves to tutor their countrymen. When the people berate them for ignoring tradition, they respond by brandishing a virulent and intolerant nationalism. The disputes that a Flaubert-like outside observer might call bizarreries may simply be the clashes between these political and economic programs and the cultural aspirations they engender. On the one hand, there is the rush to join the global economy; on the other, the angry nationalism that sees true democracy and freedom of thought as Western inventions.

V. S. Naipaul was one of the first writers to describe the private lives of the ruthless, murderous non-Western ruling élites of the post-colonial era. Last May, in Korea, when I met the great Japanese writer Kenzaburo Oe, I heard that he, too, had been attacked by nationalist extremists after stating that the ugly crimes committed by his country’s armies during the invasions of Korea and China should be openly discussed in Tokyo. The intolerance shown by the Russian state toward the Chechens and other minorities and civil-rights groups, the attacks on freedom of expression by Hindu nationalists in India, and China’s discreet ethnic cleansing of the Uighurs—all are nourished by the same contradictions.

As tomorrow’s novelists prepare to narrate the private lives of the new élites, they are no doubt expecting the West to criticize the limits that their states place on freedom of expression. But these days the lies about the war in Iraq and the reports of secret C.I.A. prisons have so damaged the West’s credibility in Turkey and in other nations that it is more and more difficult for people like me to make the case for true Western democracy in my part of the world.

MOVIES

“King Kong” and “Memoirs of a Geisha.”

by DAVID DENBY

The big guy is back: the same chocolate-doughnut nose, seriously mashed, as if he’d been sleeping face down in the jungle for decades; the matted hair, worn natural as always; the eyes both fierce and plaintive; the heavy-limbed body, though it’s stronger than before, and quicker, too. He swings his weight easily, hanging from promontories and thick vines, but he’s definitely a wrestler by temperament, taking on three allosaurs—or whatever they are—at once, and flinging them about as if they were barroom thugs. King Kong never really went away. The most familiar of pop-myth creatures, he just seemed, for some reason, to be hiding from us since his last appearance, in 1976, in which he found himself entrapped in a rather cheesy camp-colossal retelling, updated to the (then) present. That movie was a self-consciously jokey story about a greedy oil-company scouting expedition, a Princeton paleontologist (Jeff Bridges), and a ditzy starlet (Jessica Lange), who chatted to the ape as if he were hanging out in her dressing room. This new version, directed by Peter Jackson, goes back to the Depression era of the justly beloved 1933 original, which was directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack. The huckster-filmmaker Carl Denham (Jack Black) is again making a movie, and journeys by ship to a mysterious island in the South Seas, accompanied by a hungry, eager-to-perform vaudeville actress, Ann Darrow (Naomi Watts).

This time, however, the hero is a playwright and screenwriter, played by the long-faced Adrien Brody. A knight of the doleful countenance if ever there was one, Brody is perhaps not quite right as a leading man; in any case, he receives less affection from Ann than the ape does. Once she overcomes her fright, she tries to enchant Kong by putting on a show before his jungle throne overlooking a vast valley. Watts, who has a likably game quality, does corny period vaudeville stuff—cartwheels, juggling, and slinky Egyptian moves—and her solitary auditor grunts and snorts and shifts his weight. Clearly, he is amused. She learns to trust him (he has gentle hands), and, back in New York, she doesn’t want to give him up—she’s left heartbroken atop the Empire State Building, where he meets his match and dies. The first two movies were about an ape who wanted a blonde he couldn’t have, and the woman who came to like the big dope; Jackson’s version is about an impossible union between partners equally in love with each other. But nothing can compare with the original’s strange combination of naïve enthusiasm and knowing lewdness. (When Denham brought Kong and the girl back to New York, and exhibited them in a theatre, he claimed that she had “lived through an experience no other woman ever dreamed of.”) There’s no place for lewdness—for the jokes and innuendos that movie nuts have been buzzing over for decades—in this new, tender version.

I also missed any equivalent to the enchanted-isle graphics of the first movie. But there’s no point, I suppose, in shrouding computer graphics in mist, since we’re paying to see what we cannot see in life. Peter Jackson is a master of brilliantly colored fantasy. His Broadway at night, with square-backed yellow taxis and a thousand bulbs of light, is a slightly cartooned dream of thirties urban life; his jungle landscapes are treacherously lush. The trouble is that Jackson, an exuberant director, fresh from his triumph with the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, likes to shoot up a storm, and here his exuberance spills over into senselessness. The Depression background, just a few shots in the original, is stretched out here with a montage of shantytowns and strikes; the black “natives” on Skull Island—filthy, grotesque, and vicious—seem like escapees from a sideshow. Both shantytowns and “authentically” starving islanders now seem bizarrely beside the point in what is essentially a delirious pop fantasy. In the original, Kong defends his blonde against dinosaurs on Skull Island for just a couple of scenes, but here the fights go on forever. A herd of monsters panic and race down a narrow canyon, overtaking the ship’s crew, who are running before them. Later, giant cockroaches and face-grabbing worms, and all sorts of other kiddie-show horrors, stop the movie cold. Repeating what Spielberg has already accomplished in the “Jurassic Park” series, Jackson has fallen into a trap. Spectacle must be more and more astonishing or it creates as much boredom as wonder, yet it’s not easy, as filmmakers are finding out, to top what others have done and stay within a disciplined narrative; at any rate, our awareness that so little is staged in real space feeds our impatience. Even children may feel that they’ve seen it all before. This “Kong” is high-powered entertainment, but Jackson pushes too hard and loses momentum over the more than three hours of the movie. The story was always a goofy fable—that was its charm—and a well-told fable knows when to stop.

It may be as tricky to question another culture’s ideals of beauty as it is to question its religion. If I now offer a demurral on the delicate subject of the geisha mystique, I hope it will be accepted merely as an expression of personal taste. A beautiful young woman whose breasts have been flattened, her face whitened and painted over with a mask, her body swathed in layers of padding and silk to the extent that she is unable to walk normally but must hobble as gracefully as she can—none of this, as enticements go, raises my pulse rate above its usual listless beat. But obviously the opposite was true for certain Japanese men. For worshippers of the geisha, the point of obsession was the precise balance between the erotic and the anti-erotic: the clothes may have disguised the outlines of the woman’s body, but the neck, an area of major arousal for Japanese men, as the ankle was for Victorian Englishmen, had to be exposed. In general, a geisha’s ambiguous situation was the source of her power. Even as she presented herself as supremely attractive, she remained out of reach to everyone but a single wealthy protector. Arthur Golden, in his 1997 best-seller, “Memoirs of a Geisha,” worked pages of such lore into a fictionalized autobiography of a woman who triumphed in this extraordinary trade during the nineteen-thirties and forties. He opened a hidden world with fluency and grace. Yet somehow the movie that Rob Marshall has made from Golden’s novel is a snooze. How did he and the screenwriter, Robin Swicord, let their subject get away from them? Whatever my uneasiness, women who serve as geisha have been at the center of many great Japanese films, including Kenji Mizoguchi’s lyrical 1953 “Gion Bayashi.”

There is spectacle enough in Marshall’s movie—rows of geisha trainees aligned in formation like Rockettes, acres of low, cedar-and-bamboo buildings with mountains in the distance—but nothing that comes close to lyricism. What we’re presented with, at first, is a kind of crude fairy tale, in which a country girl, Chiyo, is sold into bondage at a Kyoto geisha house in 1929. The house is ruled by a foul-tempered Mother (Kaori Momoi) and a nasty head geisha, Hatsumomo (Gong Li)—the equivalents of a wicked stepmother and stepsister. But then the teen-age Chiyo (Ziyi Zhang) is rescued by a fairy godmother, Mameha (Michelle Yeoh), an older geisha who treats her kindly and teaches her the intricacies of her craft. Golden told this tale from Chiyo’s point of view, as memories of her early hardship and increasing mastery, but the movie, looking from the outside, presents the young Chiyo (Suzuka Ohgo) as a kind of exquisite punching bag and the teen-ager and the grownup woman as beautiful and tough-souled but opaque. It turns out that Marshall, the director of “Chicago” and numerous stage musicals, can’t keep a narrative moving or create interest in any of his characters. We do not initially understand, for instance, why Hatsumomo is so cruel to Chiyo, and by the time we find out we no longer care. As Hatsumomo, Gong Li is required to throw so many hissy fits that she seems less a geisha than a Mean Girl in a high-school comedy set in Santa Barbara.

Chiyo, lips painted in a crimson circle, does attain a surpassing chic, but her paramount desire, which is to preserve her virginity for the highest bidder and then become the mistress of a handsome married gent (Ken Watanabe) who was once nice to her as a little girl, isn’t very attractive psychologically, and provides little that we can root for. With the best will in the world, a Western audience could applaud Chiyo’s submission to her married protector only with the most severe irony, and Marshall isn’t capable of irony or of any other tonal variation on the literal. The movie lacks a sense of proportion: the filmmakers are so eager to pump up their subject that they don’t let us know that by the nineteen-thirties geisha were in serious decline, and that their dress and their manners, derived from an aristocratic era when elegance might have served an organic function, had become little more than decorative adornment for industrialists and bankers making deals in teahouses—in other words, that many modern Japanese may have regarded them not as unspeakably mysterious and powerful but as an increasingly rarefied and even amusing anachronism.

Beck

Beck's eyes are preternaturally blue, and until recently, exactly what lay behind them was something of an enigma. Whether clowning in videos, spontaneously breakdancing at awards shows, or just gazing ahead on his album covers, the junkyard boho was always looking beyond, seemingly into a bizarre realm unhindered by genre-- or behavioral-- expectations. But lately, he just looks lost. Wandering down a gimmicky path lined with empty pop-up confections in the "Girl" video, the 35-year-old dad with bad hair found himself relegated to the role of passerby. More than ever, 2005 saw Beck losing his edge. So, on this take two, he embraces the talent and ideas of contemporaries and descendants alike (all of whom, I'm sure, are really, really nice), hoping for a little friendly friction. Much like its inconsistent source material, Guerolito emits a few flashes but lacks the cohesiveness that was once this innovator's hallmark.

Possibly a sign of self-conscious second-guessing, Beck began to commission new mixes for Guero early on. Oddly, the lo-fi blip GameBoy Variations EP, featuring remixes for four of the album's songs, was thrown up online a full two months before Guero's official release. Then, over the course of the year, about a half-dozen more trickled out. Wisely, not all of these previously released alternates-- including lazy efforts from Dizzee Rascal and Röyksopp-- are included here. All in all, nine of Guerolito's 14 tracks are new, which, along with fresh artwork courtesy of surrealist Guero cover illustrator Marcel Dzama, and a track-for-track sequencing, indicates the intention of a true remix album rather than just another careless fourth-quarter hodge-podge ch-ching. While such efforts are duly noted, the bare-bones liners and widely varying quality of these retries make Guerolito better suited for iTunes cherry-picking than full-on Amazon consumption.

Several tracks equal or trump their initial incarnations by emphasizing pluses and playing into their remixers' entrenched strengths. Both Boards of Canada and Air are wonderfully type-cast; the former's take on "Broken Drum" highlights Beck's Sea Change-y lonesome vocals with apropos amble ambience while the latter's "Missing" redux, "Heaven Hammer", boosts sexy-church synths, echoing drums, and everything else you'd expect from France's finest purveyors of cheesy-cool. The new "Scarecrow", courtesy of El-P, is a marked improvement on its predecessor, with the hip-hop producer's succinct drums and keyboard stabs giving the song a newfound strut. Meanwhile, golden boy Diplo reiterates his current crate-king status by slowing down the staccato bass backbone of the English Beat's "Twist and Crawl" to provide his "Go It Alone" redo with a stealth funk.

Alas, many other attempts fall flat due to weak, repetitive arrangements, or an inability to convincingly congeal with their forebears. The worst offender is nerd rap group Subtle, whose lumbering "Farewell Ride" won't entice anybody to grab onto the Anticon trolley anytime soon. (I hope.) Two ex-Unicorn projects are represented, and neither clicks, though for different reasons; Islands' Uni-lite twee instrumentation sounds woefully out of place when meshed with Beck's East L.A. non-sequiturs on "Que Onda Guero" (not to mention the ill-fated, half-assed screwed 'n' chopped bit), while Th' Corn Gangg's electro R2-D2 spin on "Emergency Exit" takes too long to climax with its dense thump and cut-up vox. And just when you thought the Beasties couldn't get more annoying, Adrock comes along with his throwback minimalist-clang take on "Black Tambourine" featuring enough repeating "ugh!" and "what!" drops to make you want to steamroll your copy of Check Your Head.

His fierce glint fading, it's becoming increasingly clear that Beck is no longer able to freely revel in the youthful dalliances that made him famous more than a decade ago. Guerlito's standouts prove that proper taste and a good ear can be just as valuable as songwriting to a multi-tasker like Beck, but even for an artist this venerable, a remix record is still a remix record-- generally uneven, part enlightening, and part skippable.

TURKEY

ON TRIAL

by Orhan Pamuk

New Yorker

In Istanbul this Friday—in SiSli, the district where I have spent my whole life, in the courthouse directly opposite the three-story house where my grandmother lived alone for forty years—I will stand before a judge. My crime is to have “publicly denigrated Turkish identity.” The prosecutor will ask that I be imprisoned for three years. I should perhaps find it worrying that the Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink was tried in the same court for the same offense, under Article 301 of the same statute, and was found guilty, but I remain optimistic. For, like my lawyer, I believe that the case against me is thin; I do not think I will end up in jail.

This makes it somewhat embarrassing to see my trial overdramatized. I am only too aware that most of the Istanbul friends from whom I have sought advice have at some point undergone much harsher interrogation and lost many years to court cases and prison sentences just because of a book, just because of something they had written. Living as I do in a country that honors its pashas, saints, and policemen at every opportunity but refuses to honor its writers until they have spent years in courts and in prisons, I cannot say I was surprised to be put on trial. I understand why friends smile and say that I am at last “a real Turkish writer.” But when I uttered the words that landed me in trouble I was not seeking that kind of honor.

Last February, in an interview published in a Swiss newspaper, I said that “a million Armenians and thirty thousand Kurds had been killed in Turkey”; I went on to complain that it was taboo to discuss these matters in my country. Among the world’s serious historians, it is common knowledge that a large number of Ottoman Armenians were deported, allegedly for siding against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, and many of them were slaughtered along the way. Turkey’s spokesmen, most of whom are diplomats, continue to maintain that the death toll was much lower, that the slaughter does not count as a genocide because it was not systematic, and that in the course of the war Armenians killed many Muslims, too. This past September, however, despite opposition from the state, three highly respected Istanbul universities joined forces to hold an academic conference of scholars open to views not tolerated by the official Turkish line. Since then, for the first time in ninety years, there has been public discussion of the subject—this despite the spectre of Article 301.

If the state is prepared to go to such lengths to keep the Turkish people from knowing what happened to the Ottoman Armenians, that qualifies as a taboo. And my words caused a furor worthy of a taboo: various newspapers launched hate campaigns against me, with some right-wing (but not necessarily Islamist) columnists going as far as to say that I should be “silenced” for good; groups of nationalist extremists organized meetings and demonstrations to protest my treachery; there were public burnings of my books. Like Ka, the hero of my novel “Snow,” I discovered how it felt to have to leave one’s beloved city for a time on account of one’s political views. Because I did not want to add to the controversy, and did not want even to hear about it, I at first kept quiet, drenched in a strange sort of shame, hiding from the public, and even from my own words. Then a provincial governor ordered a burning of my books, and, following my return to Istanbul, the ?i?li public prosecutor opened the case against me, and I found myself the object of international concern.

My detractors were not motivated just by personal animosity, nor were they expressing hostility to me alone; I already knew that my case was a matter worthy of discussion in both Turkey and the outside world. This was partly because I believed that what stained a country’s “honor” was not the discussion of the black spots in its history but the impossibility of any discussion at all. But it was also because I believed that in today’s Turkey the prohibition against discussing the Ottoman Armenians was a prohibition against freedom of expression, and that the two matters were inextricably linked. Comforted as I was by the interest in my predicament and by the generous gestures of support, there were also times when I felt uneasy about finding myself caught between my country and the rest of the world.

The hardest thing was to explain why a country officially committed to entry in the European Union would wish to imprison an author whose books were well known in Europe, and why it felt compelled to play out this drama (as Conrad might have said) “under Western eyes.” This paradox cannot be explained away as simple ignorance, jealousy, or intolerance, and it is not the only paradox. What am I to make of a country that insists that the Turks, unlike their Western neighbors, are a compassionate people, incapable of genocide, while nationalist political groups are pelting me with death threats? What is the logic behind a state that complains that its enemies spread false reports about the Ottoman legacy all over the globe while it prosecutes and imprisons one writer after another, thus propagating the image of the Terrible Turk worldwide? When I think of the professor whom the state asked to give his ideas on Turkey’s minorities, and who, having produced a report that failed to please, was prosecuted, or the news that between the time I began this essay and embarked on the sentence you are now reading five more writers and journalists were charged under Article 301, I imagine that Flaubert and Nerval, the two godfathers of Orientalism, would call these incidents bizarreries, and rightly so.

That said, the drama we see unfolding is not, I think, a grotesque and inscrutable drama peculiar to Turkey; rather, it is an expression of a new global phenomenon that we are only just coming to acknowledge and that we must now begin, however slowly, to address. In recent years, we have witnessed the astounding economic rise of India and China, and in both these countries we have also seen the rapid expansion of the middle class, though I do not think we shall truly understand the people who have been part of this transformation until we have seen their private lives reflected in novels. Whatever you call these new élites—the non-Western bourgeoisie or the enriched bureaucracy—they, like the Westernizing élites in my own country, feel compelled to follow two separate and seemingly incompatible lines of action in order to legitimatize their newly acquired wealth and power. First, they must justify the rapid rise in their fortunes by assuming the idiom and the attitudes of the West; having created a demand for such knowledge, they then take it upon themselves to tutor their countrymen. When the people berate them for ignoring tradition, they respond by brandishing a virulent and intolerant nationalism. The disputes that a Flaubert-like outside observer might call bizarreries may simply be the clashes between these political and economic programs and the cultural aspirations they engender. On the one hand, there is the rush to join the global economy; on the other, the angry nationalism that sees true democracy and freedom of thought as Western inventions.

V. S. Naipaul was one of the first writers to describe the private lives of the ruthless, murderous non-Western ruling élites of the post-colonial era. Last May, in Korea, when I met the great Japanese writer Kenzaburo Oe, I heard that he, too, had been attacked by nationalist extremists after stating that the ugly crimes committed by his country’s armies during the invasions of Korea and China should be openly discussed in Tokyo. The intolerance shown by the Russian state toward the Chechens and other minorities and civil-rights groups, the attacks on freedom of expression by Hindu nationalists in India, and China’s discreet ethnic cleansing of the Uighurs—all are nourished by the same contradictions.

As tomorrow’s novelists prepare to narrate the private lives of the new élites, they are no doubt expecting the West to criticize the limits that their states place on freedom of expression. But these days the lies about the war in Iraq and the reports of secret C.I.A. prisons have so damaged the West’s credibility in Turkey and in other nations that it is more and more difficult for people like me to make the case for true Western democracy in my part of the world.

MOVIES

“King Kong” and “Memoirs of a Geisha.”

by DAVID DENBY

The big guy is back: the same chocolate-doughnut nose, seriously mashed, as if he’d been sleeping face down in the jungle for decades; the matted hair, worn natural as always; the eyes both fierce and plaintive; the heavy-limbed body, though it’s stronger than before, and quicker, too. He swings his weight easily, hanging from promontories and thick vines, but he’s definitely a wrestler by temperament, taking on three allosaurs—or whatever they are—at once, and flinging them about as if they were barroom thugs. King Kong never really went away. The most familiar of pop-myth creatures, he just seemed, for some reason, to be hiding from us since his last appearance, in 1976, in which he found himself entrapped in a rather cheesy camp-colossal retelling, updated to the (then) present. That movie was a self-consciously jokey story about a greedy oil-company scouting expedition, a Princeton paleontologist (Jeff Bridges), and a ditzy starlet (Jessica Lange), who chatted to the ape as if he were hanging out in her dressing room. This new version, directed by Peter Jackson, goes back to the Depression era of the justly beloved 1933 original, which was directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack. The huckster-filmmaker Carl Denham (Jack Black) is again making a movie, and journeys by ship to a mysterious island in the South Seas, accompanied by a hungry, eager-to-perform vaudeville actress, Ann Darrow (Naomi Watts).

This time, however, the hero is a playwright and screenwriter, played by the long-faced Adrien Brody. A knight of the doleful countenance if ever there was one, Brody is perhaps not quite right as a leading man; in any case, he receives less affection from Ann than the ape does. Once she overcomes her fright, she tries to enchant Kong by putting on a show before his jungle throne overlooking a vast valley. Watts, who has a likably game quality, does corny period vaudeville stuff—cartwheels, juggling, and slinky Egyptian moves—and her solitary auditor grunts and snorts and shifts his weight. Clearly, he is amused. She learns to trust him (he has gentle hands), and, back in New York, she doesn’t want to give him up—she’s left heartbroken atop the Empire State Building, where he meets his match and dies. The first two movies were about an ape who wanted a blonde he couldn’t have, and the woman who came to like the big dope; Jackson’s version is about an impossible union between partners equally in love with each other. But nothing can compare with the original’s strange combination of naïve enthusiasm and knowing lewdness. (When Denham brought Kong and the girl back to New York, and exhibited them in a theatre, he claimed that she had “lived through an experience no other woman ever dreamed of.”) There’s no place for lewdness—for the jokes and innuendos that movie nuts have been buzzing over for decades—in this new, tender version.

I also missed any equivalent to the enchanted-isle graphics of the first movie. But there’s no point, I suppose, in shrouding computer graphics in mist, since we’re paying to see what we cannot see in life. Peter Jackson is a master of brilliantly colored fantasy. His Broadway at night, with square-backed yellow taxis and a thousand bulbs of light, is a slightly cartooned dream of thirties urban life; his jungle landscapes are treacherously lush. The trouble is that Jackson, an exuberant director, fresh from his triumph with the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, likes to shoot up a storm, and here his exuberance spills over into senselessness. The Depression background, just a few shots in the original, is stretched out here with a montage of shantytowns and strikes; the black “natives” on Skull Island—filthy, grotesque, and vicious—seem like escapees from a sideshow. Both shantytowns and “authentically” starving islanders now seem bizarrely beside the point in what is essentially a delirious pop fantasy. In the original, Kong defends his blonde against dinosaurs on Skull Island for just a couple of scenes, but here the fights go on forever. A herd of monsters panic and race down a narrow canyon, overtaking the ship’s crew, who are running before them. Later, giant cockroaches and face-grabbing worms, and all sorts of other kiddie-show horrors, stop the movie cold. Repeating what Spielberg has already accomplished in the “Jurassic Park” series, Jackson has fallen into a trap. Spectacle must be more and more astonishing or it creates as much boredom as wonder, yet it’s not easy, as filmmakers are finding out, to top what others have done and stay within a disciplined narrative; at any rate, our awareness that so little is staged in real space feeds our impatience. Even children may feel that they’ve seen it all before. This “Kong” is high-powered entertainment, but Jackson pushes too hard and loses momentum over the more than three hours of the movie. The story was always a goofy fable—that was its charm—and a well-told fable knows when to stop.

It may be as tricky to question another culture’s ideals of beauty as it is to question its religion. If I now offer a demurral on the delicate subject of the geisha mystique, I hope it will be accepted merely as an expression of personal taste. A beautiful young woman whose breasts have been flattened, her face whitened and painted over with a mask, her body swathed in layers of padding and silk to the extent that she is unable to walk normally but must hobble as gracefully as she can—none of this, as enticements go, raises my pulse rate above its usual listless beat. But obviously the opposite was true for certain Japanese men. For worshippers of the geisha, the point of obsession was the precise balance between the erotic and the anti-erotic: the clothes may have disguised the outlines of the woman’s body, but the neck, an area of major arousal for Japanese men, as the ankle was for Victorian Englishmen, had to be exposed. In general, a geisha’s ambiguous situation was the source of her power. Even as she presented herself as supremely attractive, she remained out of reach to everyone but a single wealthy protector. Arthur Golden, in his 1997 best-seller, “Memoirs of a Geisha,” worked pages of such lore into a fictionalized autobiography of a woman who triumphed in this extraordinary trade during the nineteen-thirties and forties. He opened a hidden world with fluency and grace. Yet somehow the movie that Rob Marshall has made from Golden’s novel is a snooze. How did he and the screenwriter, Robin Swicord, let their subject get away from them? Whatever my uneasiness, women who serve as geisha have been at the center of many great Japanese films, including Kenji Mizoguchi’s lyrical 1953 “Gion Bayashi.”

There is spectacle enough in Marshall’s movie—rows of geisha trainees aligned in formation like Rockettes, acres of low, cedar-and-bamboo buildings with mountains in the distance—but nothing that comes close to lyricism. What we’re presented with, at first, is a kind of crude fairy tale, in which a country girl, Chiyo, is sold into bondage at a Kyoto geisha house in 1929. The house is ruled by a foul-tempered Mother (Kaori Momoi) and a nasty head geisha, Hatsumomo (Gong Li)—the equivalents of a wicked stepmother and stepsister. But then the teen-age Chiyo (Ziyi Zhang) is rescued by a fairy godmother, Mameha (Michelle Yeoh), an older geisha who treats her kindly and teaches her the intricacies of her craft. Golden told this tale from Chiyo’s point of view, as memories of her early hardship and increasing mastery, but the movie, looking from the outside, presents the young Chiyo (Suzuka Ohgo) as a kind of exquisite punching bag and the teen-ager and the grownup woman as beautiful and tough-souled but opaque. It turns out that Marshall, the director of “Chicago” and numerous stage musicals, can’t keep a narrative moving or create interest in any of his characters. We do not initially understand, for instance, why Hatsumomo is so cruel to Chiyo, and by the time we find out we no longer care. As Hatsumomo, Gong Li is required to throw so many hissy fits that she seems less a geisha than a Mean Girl in a high-school comedy set in Santa Barbara.

Chiyo, lips painted in a crimson circle, does attain a surpassing chic, but her paramount desire, which is to preserve her virginity for the highest bidder and then become the mistress of a handsome married gent (Ken Watanabe) who was once nice to her as a little girl, isn’t very attractive psychologically, and provides little that we can root for. With the best will in the world, a Western audience could applaud Chiyo’s submission to her married protector only with the most severe irony, and Marshall isn’t capable of irony or of any other tonal variation on the literal. The movie lacks a sense of proportion: the filmmakers are so eager to pump up their subject that they don’t let us know that by the nineteen-thirties geisha were in serious decline, and that their dress and their manners, derived from an aristocratic era when elegance might have served an organic function, had become little more than decorative adornment for industrialists and bankers making deals in teahouses—in other words, that many modern Japanese may have regarded them not as unspeakably mysterious and powerful but as an increasingly rarefied and even amusing anachronism.

12.08.2005

SONGS THAT I LIKE FOR YOU TO DOWNLOAD:

Nils Økland - "While My Guitar Gently Weeps"

Neil Young - "The Painter"

Neil Young - "Man Needs a Maid (feat. the London Symphony Orchestra)"

The Strokes - "You Only Live Once"

Imogen Heap - "Hide and Seek"

Broken Social Scene - "Ibi Dreams Of Pavement"

Sufjan Stevens - "Casimir Pulaski Day"

Dirty Three ft. Cat Power - "Great Waves"

Imogen Heap

Nils Økland - "While My Guitar Gently Weeps"

Neil Young - "The Painter"

Neil Young - "Man Needs a Maid (feat. the London Symphony Orchestra)"

The Strokes - "You Only Live Once"

Imogen Heap - "Hide and Seek"

Broken Social Scene - "Ibi Dreams Of Pavement"

Sufjan Stevens - "Casimir Pulaski Day"

Dirty Three ft. Cat Power - "Great Waves"

Imogen Heap

12.06.2005

NEIL YOUNG

Neil Young:

Dark Side of the Moon

By Jaan Uhelszki

Neil Young has long-plotted his life around the phases of the moon. Ancient and antediluvian, prehistoric and prescentient but strangely effective, Young uses the moon as a psychic touchstone--from when to plan a tour, book a studio or make a television appearance, but oddly not to plot the day he got married.

"Yup, you got me there," admits Young. "I am a strong believer in the full moon as a good time to sow creative seeds, and I try to plan everything around it." He leans a little too far back in an artful metal chair within a well-appointed conference suite at Nashville's Hermitage hotel before continuing. "Before there was organized religion, there was the moon. The Indians knew about the moon. Pagans followed the moon. I've followed it for as long as I can remember, and that's just my religion. I'm not a practicing anything, I don't have a book that I have to read. It can be dangerous working in a full moon atmosphere, because if there are things that are going to go wrong, they can really go wrong. But that's great, especially for rock 'n' roll."

Serious, intense, with hooded blue-gray eyes that always seem capable of pinning you to the opposite wall, Neil Young is as close as he ever gets to loquacious. The man who sits before me exudes an almost Zen-like composure, seemingly at peace with himself and the choices that he's made. Gone is much of that early ire, the kind of discontent that found him pitching televisions out of third-story windows into Southern California canyons, or walking off the stage at Oakland Coliseum in the middle of a song--only to be sued by one of the 14,000 concert-goers, or deciding not to show up when Buffalo Springfield was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997--firing off an angry fax after he found out that he would only be able to bring a single guest free of charge, and would have to pay the going price of $1500 for any additional family members.

Today, Neil Young wants to talk about life--in a way he rarely has. "It's so much more simple than having to follow a bunch of rules and go to a building with everybody every week. I respect people who are dedicated to organized religion, and I respect their way of life, but it's not mine. And so I feel grossly underrepresented in the current administration," he says, waiting for the full effect of his admission to be felt.

And it's felt, if not by his words then by a song like "No Wonder" from his latest and 31st album, Prairie Wind, with its pointed but subtle bashing of U.S. politics, from Young's stance on preservation of the environment to dealing with the 9/11 aftermath. Less bombastic than 2002's "Let's Roll" but perhaps more effective because of that, it's the latest in a long line of politically conscious Young songs beginning with "Ohio" in 1970 and extending through "Rockin' in the Free World," "Powderfinger," "Welfare Mothers" and so many more over the past 35 years.

"I feel I'm doing the right thing for me. And the Great Spirit has been good to me. My faith has always been there. It's just not organized. There's no story that I follow. To me the forest is my church. It's a cathedral to me. If I need to think, I'll go for a walk in the trees or I'll go for a walk on the beach. Wherever the environment is the most extreme is where I will go."

The full moon, especially, has been an enduring presence and silent witness to his life (showing up in 28 songs in his canon). It's a widely known industry secret that Young is more apt to accept a project if it coincides with a full moon--and reject one if it's not. In fact, it's no accident that this year alone, the day he began recording Prairie Wind, the filming of the companion DVD and Farm Aid all coincided with the heavenly body looming full, fat and golden in the night sky.

We're two days past full today, AND the energy is winding down a little. After all, Young has put in a good two weeks' work on the DVD to accompany Prairie Wind. His friend and filmmaker Jonathan Demme, best known for films like Stop Making Sense, Silence of the Lambs and The Manchurian Candidate, called him up and offered his services earlier this year, explaining that he was taking a year off, and wondered if there was anything that Young wanted to do. It turns out there was lots he wanted to do, but the first thing Neil wanted was to get a Florida-shaped aneurysm removed from his brain.

After inducting Chrissie Hynde and the Pretenders into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on March 14, 2005, the musician suffered what he thought was a migraine when his eyes went blurry. He realized it was something more when he noticed an irregularity in his eye the next day.

"I was shaving and I saw this thing in my eye. It was like a piece of broken glass, and it looked like it was getting bigger. I'd never had anything like it before. So I went to my doctor and he noticed a couple of other irregularities in my body, a couple of things that were danger signs to him. I said, 'Hey, you know, this thing happened to me. What's going on?' So he took me to five specialists. I was just going from one office to another, and he went with me, and took me around to all these places. And I met the heads of several departments and was looked at and they did ultrasounds and an MRI and MRA on me that night. By the next morning they had the results and I went to my neurologist and they showed me this thing in my head. And he said, "You've probably had this for 100 years, so don't worry about it. But it's very dangerous, and we have to get it out right away. When I first heard the word 'aneurysm' it was like I was watching a movie instead of having it happen to me, because I felt fine."

No stranger to health concerns, Young has had bouts with epilepsy since the age of 20, suffered from polio as a child and was forced to relearn how to walk at the age of six, undergone numerous spinal surgeries and a hearing disorder called hyperacusis continues to nag him, but he never allowed his frailties to slow him down. He just works around them.

"I set up an appointment with the head of the surgery team that was going to perform this intervention. It's not really a surgery; it's a radiological intervention," he clarifies. "I got an appointment to see him but I had four days before the appointment. It was a Thursday and the appointment was on a Monday. So I went to Nashville that night and we started recording the next morning. Then I started writing that night and in the morning I did the next song. So the words all started coming and the songs came real fast."

The studio was already booked--on March 25, a full moon, natch--so the musician flew down to Tennessee with only one song written, with plans to hook up with old cronies like Spooner Oldham, guitarist Grant Boatwright, bassist Rick Rosas, and steel guitarist Ben Keith--many of whom played on earlier albums that he recorded there, including Harvest and Comes a Time. He immortalizes those early relationships in "The Painter," the first song written for the album: "I have my friends, eternally/We left our tracks in the sound/Some of them are with me now/Some of them can't be found."

"I think my greatest strength is the ability to let myself be washed along on the top of the water, just to be able to roll along--with absolutely no control over my destination," Young tells me with complete sincerity, belying the public's long-held perception of him being more than a bit of a control freak. Although after assuring me of his pacific tendencies, less than a month later he's devoted an entire pre-Farm Aid press conference to rage about an article that appeared in the Chicago Tribune that questioned the charity's distribution of funds, chastising the publication for hurting the annual concert's reputation, not letting anyone or anything deter him from his public witch hunt, finally thundering: "The people at the Chicago Tribune should be held responsible for this piece of crap," before ripping the newspaper in half and tossing it aside, an act that was accompanied by a roomful of cheers--including cheers from some Tribune employees.

"Okay, I'm kind of a walking contradiction," he laughs in his characteristic short, two-syllable laugh that's somewhere between a chuckle and a cough. "I just do what I feel like doing, so I don't close any door. I'm just open to things. I don't close things off, I don't have a lot of beliefs that stop me from doing things. I try to be open and follow the muse wherever it goes. And if it's not around, I don't push it. There's no sense in trying to fan a flame if there's no flame. Sometimes you've got to rest --and you don't have to go against the grain."

And because of that, he felt absolutely no fear that he didn't write anything for a year and a half after 2003's Greendale, or even felt the slightest urge to pick up a guitar. "It just comes when it comes. Greendale was such a huge thing that it just drained me. I couldn't figure out whether I was going to write another story like Greendale, or whether my next album was going to be like a novel or what I was going to do, and whether it was going to have more characters, or a continuation of the same story, or--I couldn't figure out what it was so I just waited. And then, finally, after 18 months, I started picking up the guitar. I never do it if I don't feel like it. I mean I don't sit around and practice. If I don't feel like it, I don't do it. And if I do feel like it, I won't do anything else."

"But you can forget how to do it," he continues. "You can write it down at night, and get up in the morning and start playing it and not remember it, and then get it back, and then go to the studio and still not remember it. You can't box it in, you can't fence it in. If you trust yourself and you don't try to box it in, you'll get it. It's like catching a wild animal: you can't corner it, you can't scare it. But you just consistently stay there with it, and wait for it to come out."

Which is exactly what Neil Young did with Prairie Wind. But he had the added impetus of his brush with mortality. "That does give you a certain fragility. But I think I always approach my records this same way. An urgency to get the stuff out, like it might be my last one." Although with this one he was plagued by the fear that he might never play again. "I knew I was at risk, a lot of people get these things and they don't make it. I think I was more afraid that I might be incapacitated."

While he claims that fear wasn't a motivating factor in getting everything down quickly, once he got to Nashville the songs just spilled out of him--some of them coming in less than 15 minutes. He wrote at the studio and at a small desk in his hotel suite after he finished recording at the studio during the day. By the time he had to return to New York for his surgical procedure Young had penned and recorded eight numbers.

One of them, "Falling Off the Face of the Earth," he even cribbed from a phone message a friend left him after he heard of Young's aneurysm. "I copied all the words down, but I'm not going to tell you who he is, because I don't share royalties with anyone," he tells the audience with a wry smile at Nashville's Ryman Auditorium, before performing the song.

Ensconced in nashville's first "million-dollar hostelry," home for eight years to pool legend Minnesota Fats, and both the pro- and anti-suffragette movements, the Hermitage hotel has hosted throngs of celebrities from six U.S. presidents to the likes of screen legend Greta Garbo and gangster Al Capone. But Neil Young likes this place not because of its storied guests, its Italian marble or even because of their flawless egg and watercress sandwiches, but because they allow pets to actually stay in the sumptuous 2000-square-foot suites that overlook the Tennessee State Capitol. To make that fact a little more material, there's a photograph in the lobby of cowboy icon Gene Autry checking in with his horse Champion.

Young and his wife of 27 years, Pegi, travel everywhere with Carl, their apricot-colored behemoth of a Labradoodle. Carl is the latest in a long line of canines who have shared the musician's life, from the slight pooch who posed with him on the cover of 1969's Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, to Old King, a Tennessee bluetick hound whose birth name was really Elvis. But unlike his predecessor, Carl hasn't been immortalized in song. One suspects that's because Carl is markedly better behaved than his predecessor. Every night Neil, Pegi and Carl walk companionably out into the park that is adjacent to the hotel for their nightly constitutional, returning to the stately lobby where Carl gracefully picks his way between the overstuffed couches, high-backed wing chairs and the elaborate oriental rugs in the stratospheric-ceilinged lobby without ever having the slightest inclination to gnaw on a mahogany table leg or mark his territory on one of the ornately potted trees.

On the other hand, the gone-but-not forgotten Elvis not only lives on in the lyrics of "Long May He Run," but Young embellishes the story in a long, rambling, but utterly revealing preamble to the song during both of the performances at the Ryman. After listening to the story, it becomes increasingly apparent that Young has anthropomorphized the dog--into a canine stand-in for himself.

The song was inspired by a rather chilling incident when the dog disappeared, bounding off the tour bus all by himself, because Young was too tired to take him for a walk in the early morning hours. This wasn't an unusual occurrence--many times before Elvis would go romp in the fields while his family slept on the side of the road, but for some reason--perhaps a trip to a dog groomer--Elvis didn't return by the time they were due to leave for the next stop on the tour.

Distressed because rain had begun to fall, Young went on a forced march looking for the errant dog, afraid that he wouldn't be able to find his own way back to the vehicle, explaining to all of the non-dog-owners in the audience that canines always leave concentric circles of scent from their point of departure in order to find their way back. Young eventually got the dog back, due to the kindness of strangers--but that's not what's important about the story. What's telling is this is exactly what Neil Young does in terms of his career.

He leaves trails of scent so he can find his way back--whether it's to help handmaiden the Buffalo Springfield box set four years ago, to resurrect his membership in CSN&Y, to reconnect with the members of his proto-garage band Crazy Horse when he's feeling the need to make deconstructed squalls of rock, or to settle in with his Nashville cronies when he's feeling reflective, like he is now. But despite what many reviewers have surmised, Prairie Wind does not complete a trilogy of acoustic-driven albums that Young has recorded in Nashville in the past three decades

"I'm just not that calculated," insists Young. "I think things just happen because it's easy. You take a route that seems the logical route because of something that happens that day. If I've got a song that I've finished--like I finished "The Painter"--I'm sitting around going, 'I got the song now.' That sets the tone. I called up Ben [Keith] and I said, I've got one song, man. It's the first song I've written in 18 months. I don't know if I'm going to have any more, but I've got one. So maybe we'll go in the studio. And he said, 'Well, why don't you come to Nashville this time?' A couple of weeks later I called him back and said, I still don't have any more songs but let's try to book something for this full moon coming up. This had absolutely nothing to do with those other albums that I recorded there."

While Young doesn't have the geo-positioning of exactly where he's headed next, he does have some rough idea of the direction. "I'd say there is another 'Hurricane' in me, but I'm not really planning for anything like that, but I do know it'll be there. I just feel comfortable with the musicians that I'm playing with now, but I know Crazy Horse is always out there, and that's another ride completely. That's a much rougher ride."

But his former bandmates are never sure what the musician has in mind, and that makes them more than a little nervous. "Neil scares me a lot," Graham Nash, told biographer Jimmy McDonough for his 2002 biography, Shakey. "I don't understand him. I don't understand his ability to change his mind ruthlessly."

Changing his mind is something Steven Stills can no doubt attest to, when in 1976, catching a plane home and abandoning a tour with Stills, Young alerted him with a telegram that read: "Dear Stephen: Funny how something that starts spontaneously ends that way. Eat a peach, Neil."

"That could be construed as being ruthless, because someone doesn't understand that impulse," Young bristles. "They're going to think, 'Well, this guy just does exactly what he wants to do. I can't understand why he's so driven to do what's good for him, he's ruthless.' What is ruth? I don't know what ruth is. I just know that what I have to do is follow the muse, so I do what I have to do to make that happen," says Young, just this side of annoyance, his arms now folded in front of him, in a defensive posture. The first sign of any pique during this entire interview.

"I've had to do all kinds of things that as a human being I felt bad about, because working with different musicians and working with people to get where I want to go, you have to be able to sever the ties and say, 'I'm sorry. I'm not working with you now. I'm working with someone else. I'm going this way and you're not coming with me. These other people--I'm going with them now.'

"But I'm still going down the road," he continues. "They'll be down there somewhere. If they lose interest in what they're doing because they needed me, then they don't have what it takes to go on their own. In that way, I think I could be described as ruthless because I won't bend to normal considerations. It's a responsibility to be on your journey."

Only a few months from his 60th birthday, Neil Young looks like he's equal to both a journey into the present and a look back, and says as much in the first track on the new album: "It's a long road behind me, It's a long road ahead." Like the title of his 1972 soundtrack album, Journey Through the Past, the musician is eager to reflect on his beginnings--but this time he's regressed much further than his musical roots. He's returned to the tangible landscape of memory--to the Cypress River that flows through the Winnipeg farmlands where his father was born--on "Far From Home" to the emotional landscape of the title track, trying to preserve the past by snatching it from his ailing father's memory, something he expresses in Prairie Wind when he laments, "Tryin' to remember what my daddy said, Before too much time took away his head." Prior to his June passing, Young's father, Scott Young--the infamous Canadian sports writer and Hockey Hall of Famer (for sports journalism)--suffered from vascular dementia and it was difficult for the musician to communicate with him anymore. The album is dedicated "To Daddy," and while Young finished the album two months before his father's death, his spirit looms large in many of the tracks.

Dressed in a dove-grey cowboy suit, a blindingly white shirt, cowboy boots and a straw gaucho hat pulled low down on his brow and playing Hank Williams' guitar, Neil Young, along with 35 musicians, transformed his album into a historical document for Jonathan Demme's cameras over the course of two nights. With Pegi Young, Emmylou Harris and Diane Dewitt by his side in period customs nabbed from a Deadwood set, he brought the haunted beauty of the album to life--taking the briefest of intermissions and a costume change--chronologically played songs from the softer side of his extensive canon--the ying to Crazy Horse's yang--from the earliest days beginning with "I Am a Child," from Buffalo Springfield's final album, 1968's Last Time Around, through "One of the Days," from 1992's Harvest Moon.

Young is sanguine about waiting for his muse to show, and he's equally sanguine about the ghosts that parade through his life, and at the Ryman shows. "They're everywhere, there's no escaping them. But there are ghosts of the future around us, not just ghosts of the past. But I'm not really scared of them, but then, I don't think about them too much," admits Young.

One of them is Nicolette Larsen, Young's one-time inamorata and collaborator. During both shows at the Ryman, the musician paid tribute to the singer, who died in 1997 of a cerebral edema. He told a story about how Larson used to torment him with stories about how she and her friends used to mimic his trademark cracked vibrato riding around the bumpy dirt roads in Montana singing his songs. "She used to say, we're having some fun tonight," recalls Young. "This one is for you, Nicolette," he said, looking heavenward and raising a single-hand salute before launching into Ian and Sylvia's "Four Strong Winds," a song he recorded with Larson.

Most of the ghosts were friendly, with Young also mentioning the passing of hillbilly jazz fiddler Vassar Clements during the set, and the recently deceased Cajun violinist, Rufus Thibodeaux, who played with Young on Comes a Time.

Maybe it's being faced with his own mortality, but Young just seems so much more approachable than in years past. "That's just stuff that people put on me," he insists. "I think that's in everyone else's head, because it's something I really haven't been able to figure out. I don't think that people want to believe that I'm accessible. I don't think they want to believe that they may know what they need to know about me. It's really in the songs. I put as much as I can in there, there's very little that I don't say. I mean what are they going to find out? I've shown just about everything I know, and there are things in the back of my mind all the time but I don't know what they are. Yeah, sometimes I see a lot of people are really nervous, but I never really put that together with something that I did. I just go, well, it's part of fame. It's something the media has done."

No matter what he says about revealing all to his fans, there are things that the musician wants to withhold--like any details about his aneurysm. Young has said on record that he had absolutely no intention of letting anyone know that he had suffered an aneurysm, but two days after the surgery he went on a walk, and the thing burst on the street. There was blood in his shoe, and there were complications in his femoral artery, which surgeons had used to access his brain. He was unconscious and paramedics had to revive him, landing him back in the hospital. Young was scheduled to attend Canada's Juno Awards, but it was obvious he couldn't make it, so he was forced to make an announcement about what had happened.

"I came very close to no one ever knowing," Young told Time magazine's Josh Tyrangiel. "I would have had an aneurysm, got rid of it, and no one would have known the difference. It would have been so cool."

But not as cool as catching Neil Young in the act of being himself. After all the press had gone home, and the gear is on its way back to California, the musician hired a white panel van to take most band members and pals to 12th and Porter, a small, dark Nashville supper club that sits squarely on the wrong side of the tracks. The inner circle have come to see one of their brethren, Spooner Oldham perform with Billy Galewood, a singer who is dating his daughter. Going by the name of Bushwalla, the would-be son-in-law free-styled inane rhymes, while Oldham tried to keep on the organ, looking more bemused than embarrassed by the spectacle. It was clear that Galewood had no idea of Oldham's deep history and the reverence he commands in the music world, from providing the otherworldly organ sound on Percy Smith's "When a Man Loves a Woman" to cowriting the Box Tops' "Cry Like a Baby" and Aretha Franklin's "Do Right Woman."

The whole situation was a source of high amusement for Young, who kept heckling Galewood from the back of the club and chanting "Billy, Billy, Billy" after the rapper would finish a number. He watched from the crowd while his wife Pegi hops onstage to sing "Sweet Inspiration" with Spooner--another song he cowrote. Unrestrained by the period costumes of the two Ryman shows, Mrs. Young is clad in skin tight jeans that belie her 52 years, all perfect blonde hair and provocative stage movements. One look at her, it's clear that life really does begin at 50, especially if you ask her husband, who doesn't take his eyes off of her, holding his Michelob beer against his chest while he claps wildly at the close of her number. She has a clear, torchy voice and a charismatic stage presence--with far more wattage than Mrs. Bruce Springsteen ever commands.

After Pegi's number, her husband joins her onstage. Scooting in behind Oldham's rather smallish organ, Young picks out the first strains of "Oh Lonesome Me" with such little fanfare that it takes a minute to register the enormity of what's happening. "Welcome to the Young family's karaoke," one of his inner circle hisses from the side of the stage. And that's what it feels like. Unlike Elvis renting out an entire bowling alley or movie theater so he can move unnoticed and untouched by his public, Young moves effortlessly among them, although you couldn't really say that he is one of them. No matter how casual he looks or how affable he seems, there is that certain something, a different valance or supernatural weight that makes him different than the rest of us. Like Bob Dylan, Patti Smith and John Lennon, you can see that, despite his unassuming presence, he still dominates the small stage. You can't tear your eyes away, even though his performance is shambolic and a little half-assed, but far better because of it. You almost want to pinch yourself to make sure that it's really the iconic singer on the 24-foot stage. And of course it is. Perhaps his real genius is his ability to effortlessly float between worlds, from a sometimes standoffish artist who won't sign an autograph to the prankish fun hog who's buying beers for everyone within a three-foot radius. He's bigger because of his foibles, more superhuman because of his humanity.

He begins playing "The Sky Is About to Rain" and suddenly stops. "Nope, I don't want to do that one, it's too sad," he says. He sits there for a second, thinking, and puts his hands on the keyboard again, starting the song from the top. You can't really avoid the pain. The only way out of it, is through it, something the musician knows well. In addition to his own illnesses, both his sons suffer from cerebral palsy, and Pegi developed a brain tumor in 1978 and was only given a 50/50 chance of pulling through. And while his father's death was not totally unexpected, Young was at peace with it. "He doesn't loom any larger since he's gone, he's always been a big presence in my life," explained Young earlier. "I'm at peace with my relationship with him."

"Oh Lonesome Me," followed, heartfelt and as plaintive as it's ever been, with Young's voice cracking in all the right places. Pegi and singer Anthony Crawford came up onstage for "It's a Dream," and after finishing the group filed out into the hot August night as one. It was like it was a dream, leaving not a single trace except for the memory.

"I can play a few songs in a place like last night and screw half of 'em up and not even know what I'm doing," Young confides in me the next day. "I get to make all kinds of mistakes and bumble away like an old drunk up there, and people just tell me it was fantastic. Sometimes I don't get it."

And sometimes he does.

LIVE MUSIC

Live & Kicking:

Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy Picks His Essential Live Albums

By Tom Moon

When Jeff Tweedy sat down to edit the DVD that was to accompany Wilco's new, double-live Kicking Television, he was shocked by what he saw: a sea of logos and brands. "When we started, we wanted to include a lot of shots of the audience, because to us the audience is a big part of it. And everywhere you looked, there were logos. Nothing against our crowd, but everybody had a T-shirt with a slogan on it."

This triggered questions between Tweedy and his cohorts about the unintended messages (Shop Old Navy!) the band might inadvertently be sending out while sharing the fruits of several nights of music making. The band, Tweedy recalls, quickly came to a conclusion. "[We] didn't want to put a bunch of logos in our DVD. And at the same time, we didn't want it to be this hermetically sealed claustrophobic ideal of the band. Eventually we came to the conclusion that it's more fucking exciting just listening to it. Somehow it feels way more intimate and inclusive of an audience than the DVD did."

The initial motivation for Kicking Television was simple: to capture some of the changes in sound and structure that Wilco's music had undergone since the release of its 2004 album, A Ghost Is Born. The band did a multitrack recording of what Tweedy recalls as a "below-average" show in Madison, Wis., early in the tour, and decided to set up more elaborate recording equipment for its three-show homecoming run in Chicago. "The weird thing about Wilco putting out a live album," Tweedy says, "is whether we do it or not, somebody has access to every show we've ever played. All we were trying to do was present a sample of what our shows felt like a year ago."

Tweedy adds that the tapes surprised him when he listened back. "It's really loud, and raw. It might be the first Wilco record you could actually put on at a party and not have it get completely lost."

Since he'd spent so much time thinking about live records recently, we asked Tweedy to reflect on some of the live albums that are most important to him. He says he's always had a very simple test of a great live album: "If I was there, man, I would be shitting my pants. Just that simple. I almost put on the live side of [ZZ Top's] Fandango!, just for that reason. I'm not a big ZZ fan, but I would be shitting to be in the room hearing them do that. It's all about the bowels, really."

Neil Young, Live Rust (Reprise, 1979)

There's not that much Neil Young that I'm not into. But "Powderfinger" on this—he's on fire. The film was pretty miserable, but, man, the music is in its own place. I just saw him at Farm Aid. He did "Southern Man" with the Fisk University gospel choir. It was a fucking perfect performance of a classic song, and maybe my favorite moment ever of seeing live music. There was a lot of shit going on, things that seemed to fuel his anger. And an angry Neil Young, that's pretty unbeatable. That's kind of what that "Powderfinger" sounds like to me. He's invested himself in some of the fury of it.

Allman Brothers Band, Live at the Fillmore East (Polydor, 1971)

A lot of these records are just so formative for me. It's like "the sky is blue" kind of stuff. This one is one of the prime documents of rock music. It shows the chemistry of a band being so finely tuned, a band playing with one mind. And serious chops. I think I probably hated it the first time I heard it. I'd done a lot of brainwashing in the service of belonging to something I was never meant to belong to, like punk rock. The Allmans got pushed to the wrong side of the line in the sand--if you liked them, you couldn't be punk. That's the difference between listening to music and trying to fit into a mass movement. Punk was a mass movement. It required true believers to make it go. And now I see punk as just rock, another incarnation of it. In a way, it's exactly like the Allmans--people believing in themselves, and going out and doing it.

MC5, Kick Out the Jams (Elektra, 1969)

That's a document of people trying to start a mass movement and failing miserably, and being shit out of luck. There's a thing I do with some of my favorite records. I listen to them and imagine myself in the role of the person [making] that record, what they were thinking about. With this, these fantasies usually revolve around some sense of revenge. You know, kick out the jams, motherfucker. Punishing people who were mean to me. Part of what amazes me about it is that the audience is there, having their brains taken out of their skulls, totally receiving that. Another fantasy I have sometimes is imagining that I'm playing a record for some other being, not an extraterrestrial, just something from another dimension. Would I be able to play this for them and be proud of it? I'd be really proud of the MC5 at this moment, for all its flaws.

Albert Ayler, The Complete Live in Greenwich Village (Impulse, recorded 1965-1967)

This has all the best qualities of everything I find virtuous in free music. Here's somebody who can play anything he wants, and he's freed up his mind to the point where he can play like a little kid finger-paints. That's an achievement beyond learning "Flight of the Bumble Bee." I think it must have been a nice time to be able to sit in a small club and hear somebody going in that direction, to be in the company of people who are allowing him to, people who were mature enough in their listening to go with it and follow it. And hearing Ayler standing up, saying, "This is what I think sounds good." There was a lot of academic stuff [going on in free jazz] at the time, people becoming enamored with conceptualizing things. Albert Ayler never lost touch with the feeling and the soul of it.

Richard Pryor, Wanted: Richard Pryor Live in Concert (Warner Bros., 1979)

What can I say? He's funny. Still funny. What else do you want to know?

Miles Davis Quintet, The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel (Columbia, 1965)