READING1.

NameVoyager is an interactive portrait of America's name choices. Start with a "sea" of nearly 5000 names. Type a letter, and you'll zoom in to focus on how that initial has been used over the past century. Then type a few more letters, or a name. Each stripe is a timeline of one name, its width reflecting the name's changing popularity. If a name intrigues you, click on its stripe for a closer look.

More on names: How do babies with “

super-black names” fare?

So, what are the "whitest" names and the "blackest"

names?

Boys.

Girls.

2.

Why can’t anyone throw a fastball more than 100mph?

3.

Newsmap is an application that visually reflects the constantly changing landscape of the Google News news aggregator. A treemap visualization algorithm helps display the enormous amount of information gathered by the aggregator. Treemaps are traditionally space-constrained visualizations of information. Newsmap's objective takes that goal a step further and provides a tool to divide information into quickly recognizable bands which, when presented together, reveal underlying patterns in news reporting across cultures and within news segments in constant change around the globe. Newsmap does not pretend to replace the googlenews aggregator. It's objective is to simply demonstrate visually the relationships between data and the unseen patterns in news media. It is not thought to display an unbiased view of the news, on the contrary it is thought to ironically accentuate the bias of it.

4. Move over Kevin Bacon. Learn how many of Canada's Greatest are

interconnected. [Click on "Canucktions"]

5. Integrated data, video and

flying a plane.

6. The Parachute Artist: Have Tony Wheeler’s guidebooks travelled too far? by TAD FRIEND

New Yorker article on Lonely Planet guidebooksOn the evening after the rainiest summer day in Melbourne’s history, Tony Wheeler’s dinner guests, who were British, wanted to discuss the weather. Wheeler gradually redirected the conversation to the Falkland Islands. He had recently written a new Lonely Planet guide to the Falklands, and also one to East Timor, exactly the sort of backpacker destinations that he and his wife, Maureen, had in mind when they established Lonely Planet, in 1973, as the scruffy but valiant enemy of the cruise ship and the droning tour guide. The Wheelers’ guests, who were touring Australia, were Roger Twiney, a flatmate of Tony’s in England in the early seventies, and Roger’s wife, Susanne. As both couples sat in the Wheelers’ living room, watching the sun set across the Yarra River, Tony spoke of the Falklands’ king and rockhopper penguins; of tracing Ernest Shackleton’s footsteps on South Georgia Island; and of the peculiarities of the local “squidocracy,” those grown rich from fishing the cephalopod mollusk.

“But isn’t it cold, windy, inhospitable?” Roger asked. “No, no!” Tony said. “It’s just like Yorkshire.” “I’m from Yorkshire,” Susanne said, with a don’t-tell-me-about-Yorkshire tone. “Well, the Falklands actually get less snow than your home region!” Tony replied, seeming confident that she would be as delighted by this arresting fact as he was. Susanne fell silent.

A slight, graying man of fifty-eight, Tony Wheeler is at least two people. Tony No. 1, who goes to the office every day in subfusc clothing and carries a passport from his native Britain, is so self-contained that he appears, as a colleague puts it, “almost socially retarded.” When he gave me a tour of Lonely Planet’s head office, in Melbourne, not one of the three hundred eager twenty- and thirty-somethings who work there greeted him as he passed. “I met Tony in our Oakland office a few years ago and I expected him to be this huge presence, this Tony Robbins of travel,” Debra Miller, a Lonely Planet author, says. “But he’s sort of the Woody Allen of travel.”

Like one of those dehydrated sponges which inflate to astonishing size when dropped into their proper element, Wheeler becomes a vastly different and more voluble person when he’s on a trip (or recalling or anticipating a trip). This is Tony No. 2, who carries a passport from his adopted Australia. Tony No. 2 and Maureen and I were leaving the next day for the Sultanate of Oman. They were then going on to Ethiopia, and later this year Wheeler planned to visit Macau, Shanghai, Singapore, Finland, the Baltic States, Poland, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Iceland, and Japan, and to sweep from Cape Town to Casablanca by air safari.

Tony No. 2 relishes being the face of Lonely Planet and of independent travel, regularly rising before dawn—and ignoring Maureen’s tart remarks—to appear on Australia’s “Today” show, a program that he acknowledges is “pretty awful.” He is a valued guest because, having explored a hundred and seventeen countries, he can speak knowledgeably on almost any topic, from the issues faced by rickshaw drivers in Calcutta to such larger mysteries as why Egypt lacks a major industry. Like Benjamin Franklin and the Norway rat, he is a citizen of the world.

His company’s reach is equally broad. Lonely Planet now markets some six hundred and fifty titles, from “Aboriginal Australia” to “Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks,” in a hundred and eighteen countries. With annual sales of more than six million guidebooks—about a quarter of all the English-language guidebooks sold—it is the world’s largest publisher of travel guides.

“Lonely Planet is the bible in places like India,” Mark Ellingham, the founder of Rough Guides, the cheeky British series, says. “If they recommend the Resthouse Bangalore, then half the guesthouses there rename themselves Resthouse Bangalore.” The series’ authority is such that the team accompanying Jay Garner, the first American administrator of occupied Iraq, used “Lonely Planet Iraq” to draw up a list of historical sites that should not be bombed or looted. The writers Marianne Wiggins, Jilly Cooper, and Pico Iyer have used Lonely Planet guides to immerse themselves in the feel of a far-off locale for novels set in, respectively, Cameroon, Colombia, and Iran. And, in perhaps the greatest tribute, the Vietnamese have begun to manufacture ersatz Lonely Planet guides to complement their line of fake Rolexes.

At the same time, however, a number of the company’s authors worry that Lonely Planet itself has begun to manufacture ersatz Lonely Planet guides. As the company has expanded to cover Europe and America, markets already jammed with travel guides, it has been updating many of its guidebooks every two years, which requires that it use more and more contributors for each book—twenty-seven for the forthcoming edition of the United States guide alone. The books’ iconoclastic tone has been muted to cater to richer, fussier sorts of travellers, many of whom, like the Wheelers themselves, fly business class. And Lonely Planet’s original flagship, its “shoestring” series for backpackers, today makes up only three per cent of the company’s sales.

“Our Hawaii book used to be written for people who were picking their own guava and sneaking into the resort pool, and we were getting killed by the competition,” a Lonely Planet author named Sara Benson told me. “So we relaunched it for a more typical two-week American mid-market vacation. That sold, but it didn’t feel very Lonely Planet.” Every Lonely Planet series was relaunched last year in a slicker format that jettisoned much of the discussion of local history and economics; the books now commence, as most guides do, with snappy “Highlights” and “Itineraries.” “We’re trying to insinuate ourselves into Tony Wheeler’s world,” Mike Spring, the publisher of the hotels-and-fine-dining-focussed Frommer’s Travel Guides, says, “and he’s trying to insinuate himself into ours.”

Around the time of the relaunch, the Wheelers relinquished day-to-day control of the company, but they still own seventy per cent of it. Tony keeps looking for new places to cover, and he and Maureen continue to reject offers to license the company’s name. John Singleton, an Australian advertising magnate whose limited partnership owns the rest of Lonely Planet, says, “Tony and Maureen would rather be broke than be prostitutes, and God bless ’em.” Yet over the years, Wheeler seems to suspect, something essential was lost. “Those vivid colors of the early books,” he said to me, “once they get blended with so many other authors and editors and concerns about what the customer wants, they inevitably become gray and bland. It’s entropy, isn’t it?”

At dinner with the Twineys, as Tony was uncorking a fourth bottle of wine, Maureen Wheeler mentioned her chronic insomnia. An ardent woman with a deeply amused laugh, she grew up in Belfast and moved to London in 1970, at the age of twenty. Within a week, she had met Tony on a park bench when he noticed her copy of Tolstoy’s “Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth.” Before too long, they were off to Afghanistan in a decrepit 1964 Austin minivan. “I keep waking up from the same dream,” she said now. “My father, who actually died when I was twelve, is still alive, but I’m a spinster, with no prospects.” “I just had a dream where I was being chased through a shopping center, and I was in a dark room with all these doors, and they were all shut but one,” Tony said. “I was trying to get out that door, and it kept shrinking—and then about fifty women came through the door and prevented me from getting out.”

“It’s funny,” Maureen said. “Because you of all the people I know are the one person who does exactly what he wants at all times.” Her voice was taking on an Irish lilt, as it does when she gets worked up. “You’re never thwarted. You go off and do what you like and leave everyone else to clean up the mess.” “Oh, now,” Tony said. “It’s funny. I never have sexy dreams, or frightening dreams, just dreams of annoyance and frustration.” “Dreams are surreal,” Maureen said. “They reveal something important by twisting and heightening it.” “Surreal just means ‘not real,’ ” Tony said crossly. “Dreams are dumb.” In the late nineteen-eighties, I travelled in Asia for a year, and the Lonely Planet guides were my lifeline. I ate and slept where they told me to, on Khao San Road in Bangkok and Anjuna Beach in Goa; I oriented myself by their scrupulous if naïvely drawn maps; and on long bus rides I immersed myself in the Indonesia book’s explanation of the Ramayana story. The guides didn’t tell me to wear drawstring pants and Tintin T-shirts or to crash my moped—I picked that up on my own—but they did teach me, as they taught a whole generation, how to move through the world alone and with confidence.

I learned to stuff my gear into one knapsack; never to ask a local where I should eat but, rather, where he ate; never to judge a country by its capital city; never to stay near a mosque (the muezzin wakes you); how to haggle; and, crucially, when I later went to Mongolia, to shout “Nokhoi khor!”—“Hold the dog!”—before entering a yurt. When you spend months with a guidebook that speaks to you in an intimate, conversational tone, it becomes a bosom companion.

Through studying “The Lonely Planet Story” at the back of the books and talking with other travellers, I versed myself in the creation myth: how, after meandering across Asia’s Hippie Trail for nine months and fetching up in Sydney with only twenty-seven cents, the Wheelers self-published “Across Asia on the Cheap,” in 1973. The ninety-four-page pamphlet, which Tony had written at their kitchen table, sold eighty-five hundred copies in Australian bookstores. With its buccaneering opinions on the textures of daily life—“The inertial effect of religion is nowhere more clearly seen than with India’s sacred cows, they spread disease, clutter already overcrowded towns, consume scarce food (and waste paper) and provide nothing”—the book hearkened back to the confident sweep of the great European guides of a century before. Guidebooks had emerged in the early eighteen-hundreds as a resource for Byronic travellers in search of picturesque views, but the best of them illuminated an entire way of life. “Baedeker’s London and Its Environs 1900” told readers, for instance, that the city’s public baths were “chiefly for the working class who may obtain a cold bath for one penny.”

After spending another year in Asia, in 1975, Tony and Maureen holed up in a fleabag hotel in Singapore for three months while he wrote “South-East Asia on a Shoestring.” Tony’s former profession—in England, he had been an engineer at Chrysler—clearly influenced the books’ format: they read like engineering reports, with topics such as “History,” “Climate,” and “Fauna & Flora” to contend with before you got to the actual sights. This eat-your-vegetables earnestness made reading the books feel like taking up a vocation. “Lonely Planet created a floating fourth world of people who travelled full time,” Pico Iyer says. “The guides encouraged a counter-Victorian way of life, in that they exactly reversed the old imperial assumptions. Now the other cultures are seen as the wise place, and we are taught to defer to them.” A passage from my old Lonely Planet “Thailand” is illustrative:

Recently, when staying in Phuket for an extended period (Kata-Karon-Naiharn area), I talked with a few Thai bungalow/restaurant proprietors who said that nudity on the beaches was what bothered them most about foreign travellers. These Thais took nudity as a sign of disrespect on the part of the travelers for the locals, rather than as a libertarian symbol or modern custom. I was even asked to make signs that they could post forbidding or discouraging nudity—I declined, forgoing a free bungalow for my stay.

Note the pointed assertion of independence—and the seemingly casual aside that it was an “extended” stay. There was a self-righteousness about the tone, of course, but I liked that Lonely Planet, unlike the other major guidebooks, didn’t accept advertisements, and that it donated five per cent of its profits to charity. (After the tsunami in December, the company gave nearly four hundred thousand dollars toward relief efforts.) I did occasionally wonder just how independent I was learning to be. When Lonely Planet set me down on an island like Ko Samui, then relatively unspoiled but already speckled with bungalows, I realized that I was seeing a parallel Thailand that bore little relation to the “real” thing. Serving up cultural comfort food is a traditional feature—or failing—of guides. Cairo is “no more than a winter suburb of London,” an 1898 Cook’s Tours pamphlet assured tourists. Richard Bangs, the co-founder of Mountain Travel Sobek, the adventure travel company, says that Lonely Planet travellers “like to think they’re out there on the edge, but they’re all reading the bible and moving in big flocks.”

Yet Tony Wheeler’s most important advice—reprinted in the guides until last year’s relaunch—was “Just go!” Don’t book hotels, don’t worry unduly about shots and itineraries or even buying a guidebook—just go. This was an existential call to arms that amounted to a politics and even a morality: more than one Lonely Planet author told me that had George W. Bush ever really travelled abroad the United States would not have invaded Iraq. The most serious political wrangle the company has got into is over publishing its Myanmar book despite international sanctions against that country and the stand taken by the country’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning dissident, Aung San Suu Kyi, who has urged travellers to boycott the junta. Lonely Planet’s “Myanmar (Burma)” guide pays deference to her argument, and lists the ways that you can minimize supporting the government, but concludes that travel “is the type of communication that in the long term can change lives and unseat undemocratic governments.”

Movements like Lonely Planet need their martyrs, and in the eighties I heard stories in guesthouses across Asia that Tony Wheeler had recently died in spectacular fashion. There were hundreds of variations of the tale, but all had Wheeler running out of luck at the end of the trail somewhere: in a train, bus, or motorcycle accident; from malaria; at a bullfight; at the hands of the mujahideen. Not for nothing was the “South-East Asia” guide, with its distinctive yolk-colored cover, known as the “yellow bible.” Even today, there are animated discussions on Lonely Planet’s online forum, “The Thorn Tree,” about whether Wheeler is the Jesus of travel or the Moses, “since the LP was not written, it was revealed.”

High in the western Hajar mountains in northern Oman, our four-wheel-drive Honda lurched down a dirt pass. The one-lane road plunged among the crags toward the goal far below: Wadi Bani Awf, an arroyo filled with date palms, a rare vein of green in an arid land. The brakes were squeaking and giving off a worrisome odor, and my right thigh quivered from jabbing the nonexistent passenger-side brake pedal whenever Tony bent to peer at the odometer, checking the trip distances listed in the Lonely Planet guide. He wasn’t planning to write about Oman—the Wheelers were here simply out of curiosity—but he checks every fact, everywhere. As the Lonely Planet author Ryan Ver Berkmoes puts it, “Tony is a trainspotter to the world.”

“This is rather nice, isn’t it?” Tony said. “Not a bad road at all.” From the back seat, Maureen gave a small sigh. Glimpsing a sign for the mountain village of Bilad Sayt, Tony stopped just past the turnoff. “Let’s go see it, shall we?” he said. He began a three-point turn, backing toward the cliff. “Oh, dear,” Maureen said. “Oh, dear, oh, dear, oh, drat!” The car kept backing. “Stop!” He stopped, six inches from the edge, and, after a moment, we all laughed. “I’m fine and so are you,” Tony said. And the village proved to be a wonder—a cluster of mud-brick houses clinging like a wasp’s nest to a cliff, circled by falcons. We might have taken the turnoff not to Bilad Sayt but to the seventeenth century.

Travelling with the Wheelers is like that—you take every side road and see much more than you expect, much more convivially, and at much higher speed. It began at the Dubai airport: Tony and Maureen, who travel very light, charged up the stairs to get to the front of the line at immigration, leaving me feeling sheepish for taking the escalator like everyone else. As we waited at the Hertz counter, Tony studied the road map that he had brought along and announced, “Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are the two countries with the highest rate of road accidents.” Then he was largely silent as we drove south, ignoring even the first camels.

The Lonely Planet guide had been rather vague about the procedure for crossing into Oman here, near Hatta, and on arriving at the Oman border we were told that we needed first to officially leave the Emirates—there had been an unmarked checkpoint at the Hatta Fort Hotel, a few miles back. “We’re in legal limbo,” Tony said, as we headed north. “Here we are coming back to the U.A.E., and we’re going to have to explain why we haven’t left yet.” “We’re going to have to explain this better in the book,” Maureen said.

“When you’re leaving J.F.K. Airport,” Tony continued, “they don’t ask you to go to the Hilton to get your passport stamped. So this is interesting.” Finding this Tony—Tony No. 2—was like tuning in a distant radio station late at night: nothing, nothing, and then a sudden flare of chatter. This occurred whenever he saw something strange: a pedestrian underpass in the middle of nowhere, an oddly translated sign—“Sale of Ice Cubes”—or the goat souk in Nizwa, where potential buyers give the billy goats’ testicles a considering squeeze.

For more than a week, we moved through Oman’s northern, more populous half in a long, clockwise oval. The days would begin with a 7:30 A.M. breakfast at which Tony buried himself in his map and Lonely Planet’s “Oman and the United Arab Emirates” and regional Arabian Peninsula guides, plotting the stops en route to that night’s hotel, which would usually be the best available. (The Wheelers’ room at the Chedi, in the capital, Muscat, cost some four hundred dollars a night.) He would toggle between the books, frowning: the Oman book provided far better cultural context but was woefully out of date. (No new edition was being readied, because the guide had sold only thirty-two thousand copies since it was published, in 2000.) And then, abruptly, we were off. Tony drove, and Maureen chatted or sang “Landslide” or “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” in a pleasing contralto, and we were in and out of the car all day long until nightfall. A few minutes into any museum or souk, you’d see Tony’s eyes turn glassy, and he’d twitch his map-of-Africa cap and say, “On, on.”

When Wheeler was ten, he asked for a globe and a filing cabinet for Christmas, and he is still a mixture of impulsive and compulsive—ideal qualities for a guidebook writer. He told me, “To research a big guidebook, you need some people who live in the country, but you also need some parachute artists, someone who can drop into a place and quickly assimilate, who can write about anywhere. I’m a parachute artist.”

We began to orient ourselves around the country’s ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Said, whose portrait—which shows a bearded, gravely smiling man with warm brown eyes—is as omnipresent as his public-works projects. Every museum in Muscat devoted extravagant space to Qaboos’s achievements (though none mentioned, as the Lonely Planet guides did, that he had kicked out the previous sultan, his father, in a bloodless coup in 1970, or that Qaboos’s father had been so resistant to Western innovation that he had banned even eyeglasses). A phrase from the English-language Oman Daily Observer became one of our refrains: “The Sultan is always thinking of the benefit of his people.”

Well aware that the country’s petroleum reserves are dwindling, Sultan Qaboos has encouraged “Omanization,” in which guest workers will be replaced by Omanis—and yet almost every hotel and restaurant we went to was staffed by Indians. And so “Omanization” became another, mildly sardonic refrain, as recurrent as Maureen’s remark whenever we left a restaurant recommended by Lonely Planet: “Take it out of the book.”

“The Omanis don’t have a café culture, so we never see them,” Maureen remarked one morning. “Part of it is they’ve got too much money and they don’t have to work,” Tony said. Later that day, a police car pulsed its siren at us so that three black sedans could sweep by. “Mercedes, of course,” Tony said. “You spend too long in places like Tanzania, where all the rich assholes and government officials drive around in their Mercedeses, and you begin to hate that car.” “It’s not Mercedes’ fault,” Maureen said. “Yes, it is!” Tony said. “They stand for that sort of thing. As a result, I will never own a Mercedes.” (The Wheelers own an Audi, a Mini, and a Lotus.)

The day we went to Bilad Sayt, we made our way down the pass afterward and had a late lunch. Then the question was how to get back around the mountains to our hotel in Nizwa. The main road lay to the southeast, but, looking at the map, Tony suggested a more direct route to the northwest. “It’s sealed roads, all the way,” he said, asserting a faith in the map, and the Sultan’s pavers, which proved unfounded eight miles in, when the road became dirt and began to labor up into the mountains. We came to one fork, then another, then a third and a fourth, all unmarked on the map and all lacking signs. The map suggested that we should be aiming at the village of Rumaylah, but the map was ridiculous. “Every road has to lead somewhere,” Tony said, sneaking a peek at his global-positioning device and turning toward the setting sun.

“You won’t ask for directions,” Maureen said. “No real man does,” Tony said. An hour later, we were going ten miles per hour on a road that had narrowed to a sinister goat track, in a canyon that bore no trace of human passage. “All this is is a lack of information,” Tony said. “We should have asked the restaurant owner the best way.” Maureen snorted. “And then you would have said ‘Tssh!’ and we would have still come this bloody road.” They both laughed. After a few more flying U-turns—the signature Wheeler driving move—we finally emerged from the mountains at dusk, three hours later, twenty-five miles north of where we expected to be. Rumaylah remained a rumor, somewhere behind us. As we turned south for Nizwa, Maureen saw a fort to the west, and, rather in the manner of a mother trying to distract a child from an approaching ice-cream truck, began a flow of chatter about the mountains to the east. “Should we take a quick look at the fort?” Tony asked. “A drive-by fort?” We had already been to half a dozen of the country’s five hundred forts, all somewhat of a piece: the pillowed room for the wali, or governor; the dungeons; the machicolations for pouring hot date syrup on invaders. Hearing nothing from the back seat, he continued, “I think there’s probably a book on the forts of Oman.”

“We’re not going to publish it,” Maureen said. “No, I meant there probably is one out there.” “Thank God.”

The young Tony Wheeler once drew painstaking maps of his walks around the neighborhood. It was, perhaps, a way of trying to hold on to an ever-shifting landscape. Wheeler’s father was an airport manager for British Overseas Airways Corporation, the precursor to British Airways, and the family kept moving: Pakistan, the Bahamas, Canada, America, England. “Being always the outsider, never spending two whole years in the same school, it does fuck you up,” Wheeler told me.

“Tony has a story for every occasion, but he’s not very good with personal questions,” the photographer Richard I’Anson, who has often travelled with Wheeler, says. “We were in Delhi together in 1997 when he got the news that his father had died. You would possibly expect that he’d talk with his friend about that, but I knew not to ask him about it then, and I wouldn’t ask him now.” Wheeler says, “I don’t think I was particularly close to either of my parents; there was an English coolness there—though I did love going to the airport with my father. But what the hell—I’m sure Maureen and I fucked up our kids, too.” The Wheelers have two children—Tashi, now twenty-four, and Kieran, twenty-two—and they brought them along nearly everywhere; hostels were their nursery schools. “My memories are all messed up from when I was younger,” Tashi Wheeler told me, cheerfully. “Sometimes I remember a place as Peru, and it was Jakarta. We were always travelling, travelling.”

In retrospect, the growth of Lonely Planet from such rootless soil is both unlikely and entirely apt. The Wheelers came along when the world had begun to tire of the strictly-for-tourists approach of Fodor’s and Frommer’s and Fielding’s, which was packed with alarming puns (the Hotel Piccadilly in London “puts shoppers right in the limey-light”); to tire of the naïveté propounded in books such as “How to Travel Without Being Rich” (1959), which declared, “Mexico is the best place in the world for economical travelers who like to bring back things to astonish their friends . . . woven straw geegaws, works of art in tin and heaven knows what else.” “In the seventies and eighties, there hadn’t been any new guides out for decades,” Mark Ellingham, who founded the competing Rough Guides in 1981, says. Then airlines deregulated, making cheap tickets widely available, just as Vietnam and China and, later, Eastern Europe were opening up. “We filled a need, but we were young and ignorant and amateurish.”

It was only after Lonely Planet’s India guide unexpectedly sold a hundred thousand copies, in 1980, that the Wheelers realized that their scrappy startup was a real business. But the enterprise remained disarmingly ad hoc; for a time, the “Africa on a Shoestring” book said, of the Comoros Islands, “We haven’t heard of anyone going there for a long time so we have no details to offer. If you do go, please drop us a line.” “Tony and Maureen would pluck these people out of a bar, or somewhere, and have complete confidence in them,” Michelle de Kretser, a former Lonely Planet publisher who is now a novelist, says. “In 1992, they handed me this plum job, running the new Paris office, which I was totally unqualified for. I said, ‘How do I do that?’ And they said, ‘You know, just go and do it, whatever—you know.’ ” For years, whenever problems arose, Tony would respond rather as the Red Queen did to Alice, saying, “Let’s just run faster!” And for years it all worked.

The Wheelers long maintained an implicit non-aggression pact with other countercultural handbooks. But, as Tony Wheeler tells it, in 1984 he noticed that the Moon Travel Handbook’s renowned Indonesia guide was seriously out of date, so he commissioned a book on that country. After Penguin bought a majority stake in Rough Guides, in 1996, Wheeler noticed that Rough Guides were undercutting Lonely Planet’s prices. “So we thought, How can we hit back?” he told me, with a steely grin. “We targeted their twelve or so top-selling guides and produced competitive titles for every one. They stopped being so aggressive on pricing.” “Penguin is one of the most ruthless media organizations in the world—it’d be happy to squash us like a bug,” Mark Carnegie, an investment banker who sits on Lonely Planet’s board, says. (“We completely compete with Lonely Planet, but we’re not squashing people,” Andrew Welham, who supervises the Rough Guides and the DK Eyewitness series for Penguin, observes.) “But Tony is the Rupert Murdoch of the alternative travel space,” Carnegie added. “He knows when and how to squash back.”

One afternoon in Tiwi, a pretty town on the coast road to Sur, the Wheelers and I had a very good Indian-food lunch. As we strolled out to the car, a small boy in a blue soccer jersey smiled and asked for “baisa, baisa”—money. He was the first beggar we’d met. “No baisa,” Maureen said in a friendly way. She showed a real interest in children, and always replied to them. This boy waited till we got in the car and then flipped her the bird. She flipped it back: “Sit and spin, kid!”

“I don’t know if you should do that, Maur,” Tony said calmly, as he drove off. “If you know what that gesture means, that means Western women know what it means, and that reinforces the idea that they’re loose and easy.” “If I weren’t in the car, I’d slap the little bastard,” Maureen said. “Would he do that to an Arabic woman? Would he do that to his own mother?”

Thirty years ago, Wheeler took a different view of cross-cultural sexual politics. He wrote, in “Across Asia on the Cheap,” that in Muslim countries women are going to “get their little asses grabbed,” so “if you can lay hands on one of the bastards, take advantage of it and rough him up a little.” In the early days, Lonely Planet advocated what might be called a playground model of behavior: here’s the score on Lebanese grass and Balinese mushrooms, here’s where to buy carpets in Iran before child-labor laws drive up the price, here’s how to sell blood in Kuwait to pay for the rugs. You should avoid unwashed fruit, and you should wear a short-hair wig to fool the uptight cats in Singapore immigration, but, in general, the world is yours.

As the guidebooks grew up, the museum model took hold: foreign cultures are fragile, and should be observed as if through glass; a practice you abhor may simply be a custom you don’t understand. In the 1988 edition of the guide to Papua New Guinea, a notoriously lawless place, Wheeler himself wrote, “It is very easy to apply inappropriate Western criteria, and what appears to be uncontrolled anarchy is often nothing of the sort. . . . A case that appears to be straightforward assault may well be a community-sanctioned punishment. Looting a store may be in lieu of the traditional division of a big man’s estate.”

The first edition of Lonely Planet’s Japan guide, in 1981, had lengthy treatments of swinging with Japanese couples, live sex shows, and toruko, establishments where men could get soaped up to full satisfaction. Over the years, this section was pruned and then eliminated. “When we were selling five thousand Japanese guidebooks a year, who cared what we said?” Maureen told me. “At fifty thousand, you have a different responsibility.” Though sales kept rising, by the late nineties Lonely Planet had begun to falter. The company’s rapid expansion—in 2000 it published eight new series, including “Watching Wildlife” and “City Maps”—was accompanied by constant cash-flow crises. Sixty per cent of the guides weren’t getting to the printer on time. “Everyone was lovely, but no one had a clue,” Maureen said, during one stretch of driving. “When Tony was away in 1998—he was travelling a lot, because he didn’t want to deal with it—I told the managers they had to go. And I said to Tony, ‘If you let them talk you out of it, I am leaving you.’ ” Tony kept his eyes on the road. Later, Maureen told me, “Without Tony, Lonely Planet wouldn’t exist; without me, it wouldn’t have held together.” The morning after the planes hit the World Trade Center, in 2001, the company called an emergency meeting, knowing that travel was about to plummet. A hundred people (nineteen per cent of the workforce) were later laid off, and author salaries were reduced by up to thirty per cent. The company was further buffeted by SARS, the terrorist bombing in Bali, the Iraq war, and the threat of avian flu, and it lost money for two and a half years running. The relaunch, a response to all those changing conditions, subordinated editorializing to giving travellers a well-stuffed factual cushion that they could place between themselves and danger or discomfort. Call it the information model. Tony Wheeler explains, “I would expect someone writing for us about Spain to delve into bullfights, and either to say it’s a cruel and primitive spectacle or to say that it’s just as great as Hemingway said—and, either way, here are the hours the bullring is open, and do bring sunscreen.”

At the same time, “Just go” was replaced, as a corporate ethos, by the words “attitude and authority,” which one hears in the Melbourne office every fifteen seconds or so. Equally common are references to the new “consumer segmentation model,” which sorts travellers into such categories as “global nomads” and “mature adventurers.” And the company that had prided itself on not taking advertisements is about to start a hotel-booking service on its Web site. “When Tony washed up on the deserted shores of Bali thirty years ago, it was great to ‘just go,’ ” John Ryan, Lonely Planet’s digital-project manager, says. “If you just went to Bali now, you might not have a place to stay. We’re thinking about every phase of the travel cycle—dream, plan, book, go, come back—and trying to fill each one with Lonely Planet content.” Like Apple and Starbucks and Ben & Jerry’s, all of which began as plucky alternatives, Lonely Planet has become a mainstream brand.

Last year, the company grossed seventy-two million dollars, with a before-tax profit margin of seventeen per cent. But the Wheelers’ withdrawal during this tumultuous period has left many authors feeling marooned. Sixteen Lonely Planet veterans have established a private e-mail network to trade yearning recollections of the old days of unfettered travel and unedited prose, of princely royalties and heavy drinking and broken marriages. “Now authors are data collectors for editors,” the author Joe Cummings told me. The veterans gripe that the editors don’t even return their e-mails, a state of affairs they call “black hole syndrome.” For their part, the Wheelers speak of “mad-author syndrome.” But they are equally skeptical of the company’s new marketing surveys and slogans: clearly, Maureen is attitude and Tony is authority. One night over dinner at a Melbourne restaurant, Maureen said, “I used to feel that Lonely Planet was very real—we’d steam stamps off letters and reuse them, and everyone who worked there became our friends. And then we hired all these people—” “These lawyers and accountants,” Tony said. “I hate paying them. I walk through our parking garage and see a Mercedes—a Mercedes!” “Anyway,” Maureen said, “the point is, we’re learning how to be people who just inspire—but Lonely Planet doesn’t feel real to me anymore.”

One measure of how the company has changed is that when the new head of trade publishing, Roz Hopkins, took the job, in 2002, she quickly, if regretfully, cancelled Wheeler’s forthcoming book about his travels in rice-growing countries. “That sort of book had been quite a dismal failure,” she told me, referring to other idiosyncratic Wheeler efforts featuring Richard I’Anson photographs. “They don’t articulate the message of the brand.” So Wheeler wound up underwriting “Rice Trails” with nearly forty thousand dollars of his own money—effectively using Lonely Planet as a vanity press.

The Wheelers often hear complaints that they have helped to ruin certain destinations—that, as Richard Bangs, of Mountain Travel Sobek, affectionately puts it, “Tony can turn an out-of-the-way secret place like Lombok into something that’s loved to death.” They respond that change is inevitable, that guidebooks don’t inspire travel so much as channel it, and that it’s better to have educated travellers than clucks on tour buses. But the way Tony Wheeler rushes about suggests that he feels with particular keenness the age-old traveller’s anxiety about getting there before it all goes. (As early as the eighteen-seventies, John Muir denounced the tourists who were ruining Yosemite as “scum.”) Wheeler’s fears were realized at one of Oman’s signature seasonal riverbeds, Wadi Bani Khalid. As we approached the wadi, deep in the mountains, the road became a rugged dirt track and Wheeler brightened; arduousness, for him, promises happiness. Then we rounded a bend and joined a new road swarming with construction workers. He sank back as if he’d been punched: “It’s appalling!” “The Sultan is always thinking of the benefit of his people,” Maureen murmured.

After we parked, five local boys shepherded us up to the rock pools, chattering away in the universal pidgin of the tourism encounter: “Where you from? What your name? First time come Oman?” The pools were a refreshing aquamarine, but they were also clotted with trash. The boys asked us to come for a Bedouin meal, and, when we declined, one boy suggested, “Give me money—one rial.” Taking our refusal slightly sulkily, they turned back toward the parking lot. “They’ll be proper little guides soon,” Maureen said. She considered the concrete picnic areas and the beginnings of what looked like a snack stand—a grader was noisily levelling the earth nearby—and said, “You have to destroy everything in order to appreciate what you have. They’ll learn that people are paying more to get away from all this.” We were soon back on the road, heading north. “You grow up, and then you grow old,” Maureen said suddenly. “The first part is all right . . .”

The modern version of straw geegaws is cultural capital in the form of stories and photographs. “Tony and Maureen are in the travel-information insurance business,” Mark Carnegie says. “If the educated consumer is spending ten thousand dollars on a vacation, and someone says to him, ‘For an extra thirty dollars, I will give you a sunrise that will make you cry’—well, he’s going to take out that insurance.”

Even Lonely Planet, however, hasn’t figured out a way to market its epiphanies other than by using the impoverished language of travel writing. And so “palm-fringed beaches” and “lush rain forests” and other “sleepy backwaters” are invariably counterpoised against “teeming cities” with their “bustling souks.” Every region has a “colorful history” and a “rich cultural tapestry.” And every place on earth is a “land of contrasts.” As the Arabian Peninsula guide observes, “Bedouin tribesmen park 4WDs alongside goat hair tents; veiled women chat on mobile phones while awaiting laser hair removal,” and so on.

Peering through the windshield as another unnamed village ghosted by—mud-brick houses, men in white slouched in the shade—Maureen said, “We’re outsiders, we don’t speak the language, we only glean what we can through what we read. I can see their lives, but I’d love to be in their heads for a few hours—what’s it like to be their lives?” Entranced by every sort of strangeness, Tony often wondered aloud: What are these “pee caps” that hotel bars forbid you to wear? Why are there so many “Gents Tailors” in the town of Sohar? But he never stopped, preferring to note the street misnamed on Lonely Planet’s Sohar map, and the absence of the promised biryani joints. He wants to discover by observation or exploration, but not to have to ask, a form of cheating. When I was younger, I might have inquired more myself—there was a time when every new thing, even durian slushies, seemed worth investigating. But now, I realized, I had been perfectly content to follow Wheeler’s lead, and so I was leaving Oman with a thoroughly researched yet tentative impression of a country of

forts, wadis, and a pleasant capital, Muscat.

I asked Wheeler what he thought Lonely Planet should do about Oman. He suggested that a small, high-priced book that focussed on the forts, the wadis, and Muscat might work—but in truth he seemed to be already looking ahead to his next destination, Ethiopia, and then to all the trips beyond. “In the early days,” he said, “doing the third or fourth edition of ‘South-East Asia on a Shoestring,’ I remember feeling like we were trapped: We set this up to travel, and all we’re doing is going to Singapore and Bangkok over and over, updating. ” “Now that the company is launched, Tony can really travel,” Maureen said. Tony thought that over, its possible meanings, and replied, “In many ways, I don’t think we’ve travelled a lot, because we’ve had the business distracting us. It got in the way.”

Late one afternoon, we hiked up Wadi Shab, a steep canyon. The first hour was an easy hike, and then it became a scramble over shaley outcroppings and around acacia thorns. Finally, as the canyon filled with shadows, we arrived at a crisp blue pool where a few local teen-agers were splashing about and diving into the adjacent underground caves. The last rays of sun lit the spot: a perfect reward after a long drive and a healthy walk. But Tony shifted with frustration as Maureen and I sat on a boulder and turned our faces to the sun. He had noticed three tourists in bathing suits above us on the faint indications of a trail. “I’ll just go on for twenty more minutes,” Tony said. We got up and walked with him a ways, and then Maureen took up a perch against the canyon wall. “I’m not going on,” she said. “I’ll stay here.” I was thinking about nightfall, and finding the path down, and the two-hour drive along the sea cliffs to the hotel.

“Well, I’m just going on for a bit,” he said. Having, across the years, thrown off most of his burdens, Tony No. 1 now adjusted the one piece of baggage that remained—his backpack, which was ringed with sweat—and strode on as Tony No. 2. Or was it the reverse? In a few moments, he was around the corner. “The trick with Tony is, if I’d been in that comfortable place by the pool he would have gone on and on,” Maureen said. “But, knowing I’m in this uncomfortable place, he’ll feel guilty and come back sooner. He has to go around that bend, though—it’s his obsession. He has to go farther than the tourists. And, if there’s someone else around that bend, he’ll keep going until he’s past them, until he’s the farthest out.”

7.

Where is the U.S. dollar going?New Yorker

In the 2004 Hollywood comedy “EuroTrip,” which chronicles the adventures of a group of American teen-agers on a debased modern version of the Grand Tour, our heroes end up trapped in Bratislava with a mere $1.83 in their pockets. Things look bleak, until they discover just what a dollar and change will buy: a luxury suite, massages, three-course meals with champagne, and assiduously servile service. Feeling flush, they toss their waiter a five-cent tip. He turns to his boss and says, “A nickel! You see this? I quit! I open my own hotel.”

If only. Nowadays, when you’re abroad, you’re lucky if $1.83 buys you a cup of coffee. In the past three years, the value of the dollar has fallen by more than fifty per cent against the euro and twenty-five per cent against the yen, and, a recent rally notwithstanding, most analysts say that the dollar is only going to get weaker in the months to come. Europeans now routinely fly across the Atlantic to go shopping, and they have also started to nose around in the American real-estate market. You know the dollar’s in trouble when our puffed-up real estate starts looking cheap.

The dollar has fallen for a simple reason: Americans spend a lot more than they save. American consumers, of course, are known for living on credit, and they buy hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth a year of foreign goods—cars, TVs, T-shirts, khakis. In addition, since 2001 the American government has been running giant budget deficits, thanks to the magical combination of tax cuts and spending increases. We don’t have enough money at home to pay for all this spending, so we borrow from foreigners to make up the difference. Because we keep piling on this foreign debt—more than three trillion dollars so far—and have no clear strategy for paying it back, people are made anxious about the United States economy; this anxiety encourages them to sell dollars, and that drives down the value of our currency.

The dollar’s decline, grim as it seems, has so far had little impact on the everyday lives of most Americans. To be sure, there are new burdens: the price of truffles is up sharply, and the cost of a trip to Paris now rivals that of a semester in college. But inflation and interest rates are still low, the stock market is above where it was three years ago, and Americans have had no trouble slaking their appetite for foreign-made goods. Doomsayers have been predicting for a while that the profligacy will lead to serious trouble. So why hasn’t it?

One answer is that Asia won’t let it. Last year, Asian countries invested almost four hundred billion dollars in the United States, mostly in government bonds. China is effectively taking most of its excess national savings and lending it to the United States. The Japanese, who despite their creaking economy remain flush with savings, bought a quarter trillion dollars of American debt last year, even though the interest is lousy and the assets themselves are losing value. More than any other nation in history, the United States depends, economically, on the kindness of strangers. Right now, Asian investors appear very kind.

Markets are hardly known for their tenderness. Usually, you can assume that everyone in a market is trying to make as much money as possible, with as little risk, but the currency market isn’t like most others. In the market for the dollar, many of the players have other things on their mind. China needs to go on selling Americans hundreds of billions in exports in order to keep its economy humming. A weaker dollar makes that harder. Asian central banks also already own trillions of dollars in American assets. As the dollar falls, so does the value of those assets. There are plenty of other traders in the currency markets—who have the luxury of being single-minded regarding profit—but the Asian banks are powerful enough to be, in effect, the lenders of last resort. As long as it’s in their self-interest to keep America afloat, the dollar will not crash.

Of course, the Chinese and the Japanese could decide that the costs of the falling dollar are too great, and suddenly stop (or, at least, cut back sharply) their lending to the United States. This would lead to a so-called “hard landing” for the U.S. economy: high inflation, punitive interest rates, collapsing stock prices and housing prices. It would also lead to bedlam for China and Japan. Their best customers would effectively be unable to afford their wares. To paraphrase John Paul Getty: If you owe the bank a hundred dollars, you’ve got a problem. If you owe the bank three trillion dollars, the bank’s got a problem.

There’s a good chance, then, that the landing will be soft—we lose the truffles but keep our homes—as long as everyone involved in keeping the dollar aloft continues to play the same game. No one, in Asia or anywhere else, wants to be the last guy out. What the Chinese and the Japanese do depends in large part on what they think everyone else is going to do. If the Chinese get the idea that Japan’s commitment to the dollar is wavering, or if they decide that the United States has no interest in altering its deadbeat ways, then they may try to make a run for it. Then again, that threat could act as a prod to keep the Americans in line. The currency market is a great example of what George Soros calls “reflexivity”: people’s predictions about what will happen to the dollar end up having a major impact on what actually does happen to the dollar. Our lenders are trying to strike a delicate balance: they’d like the dollar’s predicament to seem dire enough to make us change, but not so dire as to spark panic. So be afraid. Just don’t be very afraid.

In this magazine, also read Nick Paumgarten’s Dangerous Game: The hazardous allure of backcountry skiing.

8. The Glow House

Located at 323 Palmerston Boulevard (North of College Street)

Running from 7to 23 April, 2005

Kelly Mark’s Glow House #3 is a project set in a Toronto residence, a typical detached urban house, where a number of television sets have been distributed throughout the interior. All the televisions are tuned to the same channel, and when the house is viewed from the street at night, the effect of each small flicker of light from every CRT is compounded, together becoming a vivid “pulse” of light emanating from its windows. As the television program scenes change, the windows flash in sync, and the pronounced hypnotic effect grows with the sensation that the house interior may be filled not with many lights but with one large, palpitating source.

8.5

A polar bear chased by hungry whales.

9. Jorge Drexler, Eco

"Drexler won the Oscar for best original song for "Al otro lado del río" (from The Motorcycle Diaries). Eco is his most recent album, available only as an import and totally in Spanish, so we only catch, like, every fifth word. One of the songs is either about shirt buttons or bottle caps. Doesn't matter. This stuff grooves. Extra props to Drexler for managing not to hurl during the sacrilege that was Antonio Banderas's performance at the Oscars."

10. Songs of the Day:

The theme from

The OfficeMaps – Yeah Yeah Yeahs

Kite – U2

Is a Woman – Lambchop

The Blower’s Daughter – Damien Rice

Earthquake Weather – Beck

Here, My Dear – Marvin Gaye

A Man and a Woman – U2

Thrasher – Neil Young

Stardust – Willie Nelson

Not about Love – Fiona Apple

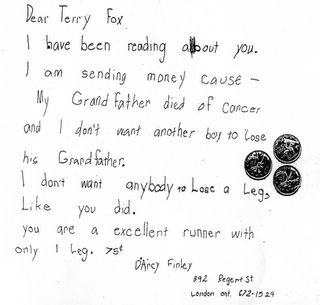

11. Remembering

Terry Fox 12.

ART: CY TWOMBLYSee this essay on

Cy Twombly’s art.

Cy Twombly

The Four Seasons: Summer

1994, Synthetic polymer paint, oil, pencil and crayon on canvas

10' 3 3/4" x 6' 7 1/8" (314.5 x 201 cm)

Cy Twombly

Tiznit

1953

White lead, house paint, crayon, and pencil on canvas

53 1/2" x 6' 2 1/2" (135.9 x 189.2 cm)

Cy Twombly

Wilder Shores of Love

1985

Oil, crayon, and pencil on plywood

55 1/8 x 47 1/4" (140 x 120 cm)